Opinion: World Economy Shows Less Resilience to Future Financial Shocks

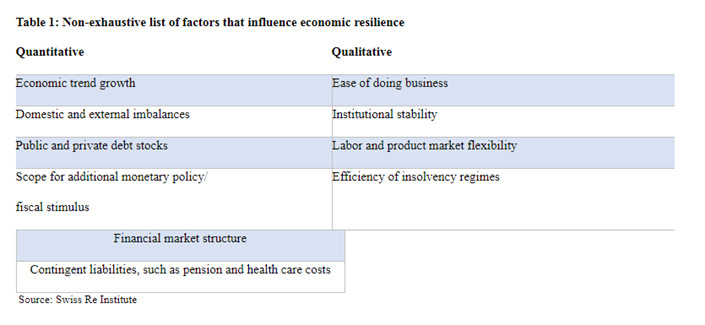

I do not think the global economy has become more resilient. On the contrary: Ten years after the 2008-09 global financial crisis, the world economy remains ill-prepared for the possibility of a repeat event. While every bank and economic research house is busy making point forecasts — we as well — the key in my view is defining “resilience” as the capacity of a system to regenerate after a significant shock event. Shock buffer capacity is a blend of quantitative and qualitative factors, including trend growth, public and private debt stocks, institutional stability, etc.

The world is less resilient to shock events

Let’s look at the capacity of several key global resilience factors, or shock buffers (see also Table 1). The fact is, they have weakened over the last 10 years.

First, see the trend growth paths: Global economic trend growth has declined significantly. According to some estimates, the growth trend has decreased from around 5% in 2006 to just over 3% in 2018.

Second, the debt picture is not better either: Total debt ratios are much higher than 10 years ago, standing at 318% of gross domestic product (GDP) in the first quarter of this year, compared with 282% in the first quarter of 2008, according to the Global Debt Monitor database of the Institute of International Finance.

Third and on the financial market structure: Central banks have become major actors in financial markets. We estimate that the Fed, European Central Bank, Bank of England and Bank of Japan all own 20% to 45% of their domestic government bond markets. Bond prices have thus lost their price/risk signaling function. This is important as it means the allocation of capital is not efficient after all with distorted “risk-free” rates. The fact is: The amount of negative yielding sovereign debt is increasing again, and amounts to $9.5 trillion, to about the economic size of China!

Finally and on the openness of capital markets: Some advanced economies have exhibited a tendency toward less-open systems in the past years; for example, by restricting trade and migration. Openness increases exposure to crisis via contagion, but arguably, openness also allows stricken nations to bounce back more quickly.

|

Where does Asia stand?

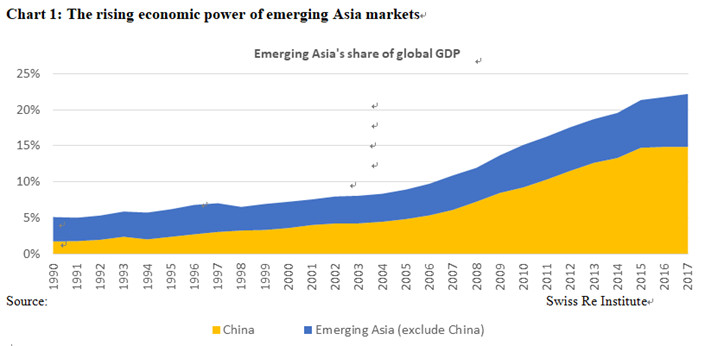

Where does Asia stand on these figures? The shift of economic power eastward continues unabated. Emerging Asia accounted for 5% of GDP in 1990, 12% in 2008, and 22% in 2017 (see chart). This shift reflects the structural resurgence of China, but also the improving resilience of many Southeast and South Asian emerging markets like Indonesia, Thailand and India. China is now the second-largest economy in the world on actual market exchange rates.

The outlook of emerging Asian markets remains sanguine. Compared to advanced economies, they continue to be more attractive. I expect this to remain the case and see many countries in Asia being better prepared to face the future economic challenges posed by demographics. One reason thereof is the long-term policy focus. This matters, and in my view, will matter increasingly so.

|

How to strengthen economic resilience

As rectifying measures, among others we encourage more private capital market solutions, with the public sector establishing financial market standards wherever possible (for example, for sustainable investment), state contingent debt instruments for sovereigns, and leveraging multinational development banks balance sheet more (see Table 2). Insurance is another central component of system resilience. It plays a vital role in stabilizing financial volatility for households and businesses. Public-private partnerships are key to foster mutual support for economic development goals. Private capital market solutions need to be encouraged for sustainable investing as well as new savings type products. The opportunities and benefits for the broader society would be great in allowing more risk-taking to take place and better recycling back savings to the real economy.

|

Looking ahead, there are four P’s to watch in 2019: prices (inflation), policies (from quantitative easing to quantitative tightening), politics (trade war, Brexit, U.S. constitutional crisis) and the Year of the Pig! In the famous English novel “Animal Farm,” written by George Orwell, pigs are the most intelligent ones on the farm. (2019 could be a tricky year!) In Chinese culture, pigs are the symbol of wealth, but are probably not associated with great momentum of work. That may explain why we expect a slower China and global growth momentum.

We will work further on how we can make the global economic system safer and more sustainable. Looking back to the last few weeks with the volatility in risky asset classes having increased globally, I would hope more research houses join forces in developing solutions and work with the public sector. It is high time to act.

Jerome Haegeli is group chief economist for Swiss Reinsurance Company Ltd. and managing editor of Sigma.

If you want to submit an opinion piece to Caixin Global, please send an email to gangwu@caixin.com.

- 1Luckin-Backer Centurium Capital to Buy Blue Bottle Coffee From Nestlé

- 2Two Sessions: With 4.5%-5% Growth Target, China Aims to Create Space for Reform

- 3China Business Uncovered Podcast: Brazil’s ‘Very Chinese Moment’

- 4Cover Story: How China’s Growing Gig Economy Has Left a Generation Adrift

- 5First Tanker Crosses Strait of Hormuz Since Iran’s Closure Threat

- 1Power To The People: Pintec Serves A Booming Consumer Class

- 2Largest hotel group in Europe accepts UnionPay

- 3UnionPay mobile QuickPass debuts in Hong Kong

- 4UnionPay International launches premium catering privilege U Dining Collection

- 5UnionPay International’s U Plan has covered over 1600 stores overseas