China Begins Efforts to Tame Asset Management Industry

(Beijing) — China’s financial regulators are embarking on what’s likely to be a long and hard-fought battle to bring the unwieldy 100 trillion yuan ($14.6 trillion) asset management industry under control.

They made a bold and unprecedented display of unity last week by proposing, for the first time, one overarching regulatory framework that transcends their respective individual jurisdictions and allows them to rein in increasingly risky practices that the central bank has already warned are endangering financial stability.

But the first salvo may have been the easiest. Documents seen by Caixin reveal disagreements among regulators over details such as data collection, which could present stumbling blocks to implementation and effective supervision. Officials interviewed by Caixin said they are concerned that some of the provisions cannot be enforced because there are no laws to support them.

Financial authorities have become increasingly concerned about the explosive growth in the issuance of asset-management products (AMPs) over the last few years. The popularity of such products has soared among investors because they offer higher returns than bank deposits, and the institutions selling the products like them because they can earn fat commissions and bonuses.

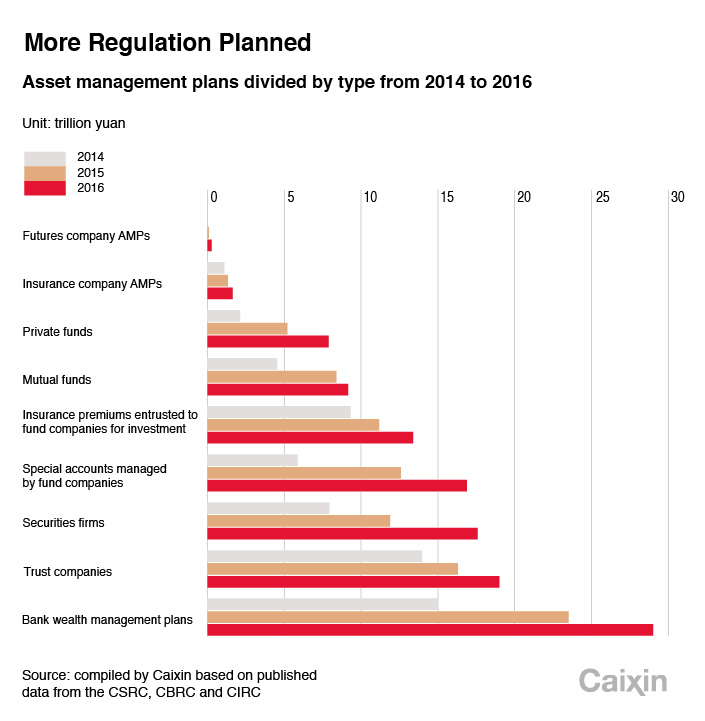

At the end of 2016, there was about 100 trillion yuan of asset-management products outstanding, data compiled from various regulators show, underscoring the explosive growth in the industry over the last three years.

|

Figures from the Asset Management Association of China show that at the end of 2016, the value of AMPs managed by securities firms, fund management companies and futures brokerages had quadrupled to 51.79 trillion yuan from 13 trillion at the end of 2014. The value of outstanding wealth-management products (WMPs) issued by banks by the end of June 2016 was 26 trillion yuan, up from 15 trillion yuan at the end of 2014.

The government has over the years encouraged the growth of the asset-management industry as part of its financial liberalization policy and to reduce the economy’s dependence on the banking system for funding. But authorities became increasingly concerned about the liquidity risks posed by the mismatch between the maturity of the money raised and the underlying assets being invested in, and also that the interest rates being offered to investors were unsustainably high.

Banks were using the products to shift loans off their balance sheets to circumvent loan quotas and various regulatory requirements. The fact that institutions were increasingly repackaging AMPs and selling them to each other only added to the complexity and interconnectedness of the financial system and increased the risks that one failure could lead to a disorderly unwinding of a chain of liabilities.

The other main problem was that of moral hazards that led to excessive risk-taking. Over the years, investors had gained the impression that nearly all financial products sold to the public came with an implicit guarantee that the government would come to the rescue in the event of a failure. As a result, they invested without proper care and attention.

Loopholes Exploited

The China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC) has jurisdiction over mainly banks and trust companies; the China Insurance Regulatory Commission (CIRC) oversees insurance companies; and the China Securities Regulatory Commission supervises all other financial institutions.

With each commission having its own rules and overseeing different parts of the financial industry, it became increasingly difficult to effectively supervise institutions. The lack of a unified regulatory system created loopholes that were easily exploited.

A crackdown by one authority only led companies to find innovative ways to get around the rules by inventing new products that put them under the supervision of another regulator that had different requirements.

For example, a bank makes a loan without recording it on its balance sheet by first purchasing an AMP issued by a securities firm, which in turn uses the money to buy a trust company’s AMP. The trust company uses the proceeds to lend to, or make an equity investment in, a company that for various reasons cannot borrow directly from the bank. This kind of arrangement allows the bank to make investments that may otherwise be prohibited, to lend out more than its quota, and to earn a higher return than it would on an ordinary bank loan.

It takes a significant amount of coordination between the banking and securities regulators to simply gather the information to decide whether an AMP is in fact a bank loan in disguise. Drafting and implementing effective rules to bring financial institutions and AMPs under control would represent a mammoth undertaking.

It’s not as if the regulators didn’t try. Sources have told Caixin that the central government put the CSRC in charge of efforts to unify regulations for AMP in 2015, but the project was shelved during the stock market crash that summer. After the market stabilized, the central bank took the reins instead with an enhanced sense of urgency to push forward reforms.

All three watchdogs announced measures last year to align their asset management regulations. The CSRC and the CIRC published new rules that put a greater emphasis on transparency and reduced ceilings on the ratio of secured versus risky investments in structured AMP. The CBRC released draft regulations for bank wealth management products with similar requirements, but has yet to announce the final version.

But the central bank decided enough was enough, as financial risks grew along with the PBOC’s frustration at seeing the watchdogs outwitted by financial institutions in their cat-and-mouse games of regulatory arbitrage. In December, it started drafting rules to consolidate and reconcile the different asset-management regulations, and in January it sent them to the three commissions for feedback, sources close to the regulators told Caixin.

The PBOC’s proposals cut across regulatory boundaries and set up unified standards and requirements for all AMPs, with rules that focus not on the type of institution offering the product but on how the product is sold — whether publicly or privately — and what type of asset is involved, such as whether the AMP comprises more bond or equity investments.

The rules will apply to almost all AMPs, including but not limited to those managed by banks, trust companies, securities firms, insurers, futures brokerages, private and public funds as well as their subsidiaries, according to documents obtained by Caixin.

Regulators Disagree

The draft rules are still subject to change, and it is unclear when a final version will be announced. Nevertheless, Beijing’s approach is clear — all AMPs, as long as they are of a similar nature, must follow the same requirements in terms of asset allocation and risk control, regardless of what type of institution is issuing the product.

But documents seen by Caixin show the extent of disagreements among regulators about the new framework.

The CBRC, for example, wanted to outlaw all structured AMPs in which a single plan is split into tranches and investors in the riskier tranches absorb losses before others in exchange for higher expected returns. The watchdog had already proposed banning such products in its own draft rules for bank wealth management products.

The central bank and the insurance regulator, however, wanted to allow structured AMP for some financial institutions that serve more sophisticated investors, according to the documents.

So instead of an across-the-board ban, the draft of the new unified regulations permits structured AMPs, with certain limits, in line with the criteria set out by the CIRC and CSRC in their own rules last year.

Material documenting the opinions of the different regulators on the draft rules show that the central bank failed to get the commissions to agree on a centralized information collection and reporting system for financial institutions to report data on their AMPs directly to the PBOC.

The central bank views comprehensive data reporting as the foundation of more-effective regulation. “At present, the parameters, methodologies, frequency of reporting and structural design of the reporting system used by different regulatory departments to supervise AMPs have been inconsistent and have overlapped,” the PBOC wrote, according to the document.

“Simply adding them together cannot generate a full picture of the industry correctly,” the central bank said. That’s why there must be a new “comprehensive statistical system that has full coverage and unified standards.”

But the CIRC and the CBRC opposed the idea, according to the documents. The insurance watchdog wanted regulators to stick to their existing data collecting systems and share their information with the PBOC. The banking commission said it was “inadvisable to build redundant data infrastructure and have financial institutions report to multiple regulators at the same time.” It said individual regulatory departments should be allowed to determine their own rules for data reporting.

The documents seen by Caixin did not contain the views of the CSRC on this issue.

Implementation Is Key

Analysts have given a mixed response to the draft regulations. Many of the provisions already exist in one form or another in the rules of the individual regulatory bodies. For this new framework to succeed where previous attempts failed, implementation will be the key.

The signs are not optimistic.

Two officials from different regulatory bodies told Caixin that some of the requirements conflict with parts of existing laws that govern the trust, securities and investment-fund industries. Some provisions lack any legal basis in current legislation governing commercial banks and insurance companies, they said.

Some provisions in the new unified regulatory framework may require revisions in legislation, and may be a catalyst for lawmakers to make changes that are needed in any case to improve the overall regulation of the industry.

The law on investment funds, for example, technically applies only to mutual funds overseen by the CSRC. But some banks and insurance companies have been awarded licenses to offer and manage mutual funds. So there is ambiguity on whether the law also applies to the mutual funds managed by banks and insurance companies, which are supervised by the CBRC and CIRC respectively, the officials pointed out.

It will take time for officials and lawmakers to comb through the legislation and existing regulations to resolve the conflicts and ambiguities. Nevertheless, the wheels have been set in motion, and financial institutions have finally been put on notice that their freewheeling days are over.

Contact reporter Wang Yuqian (yuqianwang@caixin.com)

- 1Cover Story: China Carves Out a Narrow Path for Offshore Asset Tokenization

- 2Drownings Shake Chinese Enthusiasm for Travel to Russia

- 3Over Half of China’s Provinces Cut Revenue Targets

- 4Li Ka-Shing’s Port Empire Hit by Forced Takeover Amid Panama Legal Dispute

- 5In Depth: China’s Mutual Fund Industry Faces Overhaul After a Banner 2025

- 1Power To The People: Pintec Serves A Booming Consumer Class

- 2Largest hotel group in Europe accepts UnionPay

- 3UnionPay mobile QuickPass debuts in Hong Kong

- 4UnionPay International launches premium catering privilege U Dining Collection

- 5UnionPay International’s U Plan has covered over 1600 stores overseas