Retracted Paper Controversy Puts China’s Research Under Microscope

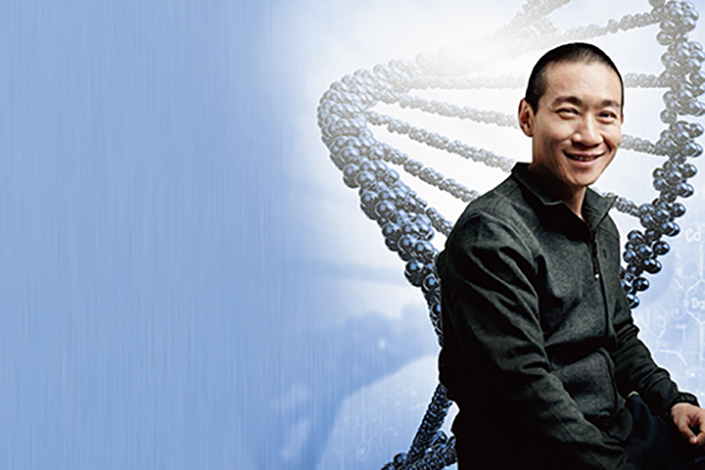

(Beijing) — When genetics researcher Han Chunyu and his colleagues at Hebei University of Science of Technology unveiled their unique genome editing technique in the journal Nature Biotechnology last year, scientists around the world took note.

And after China’s academic community said the achievement merited a Nobel Prize, the 42-year old associate professor and his colleagues were showered with prestige, accolades and government support.

Scientists in China and abroad said the apparent discovery of a genome editing technique that improved what’s currently in use held out prospects for curing cancer and even reversing the aging process.

But the euphoria surrounding the findings quickly gave way to skepticism after scientists in Australia, Spain and China reported they could not replicate the Han team’s experiment. Those reports triggered months of intense scrutiny targeting the study and Han’s credentials.

In August, the Han team bowed to mounting pressure by retracting the academic paper. But the scientists admitted no shortcomings in their research.

In an open letter published by Nature Biotechnology on August 2, the Chinese team acknowledged that peers using their original research protocol had failed to replicate their findings.

“We are therefore retracting our initial report at this time to maintain the integrity of the scientific record,” they wrote. “We nevertheless continue to investigate the reasons for this lack of reproducibility with the aim of providing an optimized protocol.”

Meanwhile, Han’s team stuck to what has been from the start of the controversy — and still is today — their hardline position on data sharing: The team has repeatedly brushed off calls from other scientists for access to original data and information about the conditions under which the experiments were conducted.

Access to such data is considered essential among academic scientists. Without it, peers can neither investigate nor endorse a research team’s findings.

Moreover, information about the Han team’s genome editing could help other researchers find and identify any flaws in the process. Without data, no one beyond the team can attempt to find out what went right or wrong.

The written retraction did not imply any academic irregularities by Han’s team, according to Rao Yao, a professor at Peking University known for his work in the life sciences field.

|

A researcher at Han Chunyu’s lab at Hebei University of Science & Technology works on an experiment in August 2016 without wearing a required lab coat or gloves, while another violates rules by eating in the lab. Photo: Zhou Chen/Caixin |

“The scientific community in China is at a critical juncture at the moment,” he said. The community “needs to take the issue seriously to defend scientific rigor in China.”

Red flags

Chinese academics are no strangers to research-related controversy, as several scandals have erupted in recent years involving plagiarized content in academic papers and fake peer reviews published in international research journals.

In April, for example, the Berlin-based academic publisher Springer Nature retracted more than 100 papers authored by Chinese contributors and published in the journal Tumor Biology between 2012 and 2016. The publisher said Chinese authors had given journal editors phony contact information for supposed third-party reviewers.

The Han team’s research on genome editing using bacteria known as Natronobacterium gregoryi Argonaute, or NgAgo, raised red flags about two months after their paper’s publication.

First to question the experiment was Gaetan Burgio, a genetics professor at Australian National University. He reported in a blog entry being unable to replicate Han’s experiment using a different sequence of genes from the zygote of a mouse.

Moreover, Burgio said one of his findings conflicted with a Han team result. His experiments suggested the NgAgo enzyme must be heated to more than 50 degrees Celsius before it can function, while the Han team paper put the functional temperature at 37 degrees Celsius.

Lab researchers at Spain’s National Center for Biotechnology reported after conducting an experiment similar to the Han team’s that they had failed to achieve promising results. Later, Han declined to share data or describe his experiment’s exact conditions when queried by the Spanish lab’s scientist Lluis Montoliu.

Unlike many academics working at universities and labs across China, Han did not study abroad. His findings were therefore held high as an example of homegrown achievement. And as a homegrown scientist, he was given special honor.

For example, Han’s university recommended he compete for the prestigious Chang Jiang Scholars Program sponsored by the Ministry of Education and the Li Ka-shing Foundation, which was established in 1980 by the wealthy Hong Kong businessman of the same name.

Weeks later, Han was elected vice chairman of the government-backed Hebei Association for Science and Technology. Shortly thereafter, a provincial economic planning agency budgeted 224 million yuan ($33.59 million) for a genome editing research center at his university.

On top of that, the Han team received 1 million yuan from the National Natural Science Foundation to finance their genome research through 2018.

Publicity surrounding the honors and government payments drew an enormous amount of Chinese media attention. Nearly 4,000 news stories about Han were published within two months of the academic paper’s publication, Nature Biotechnology said in a recent editorial about the controversy, citing the media monitor Meltwater.

Domestic scrutiny

The publicity raised eyebrows among Chinese scientists, including some who later tried the Han team’s experiment and failed.

Researchers at a lab affiliated with Peking University’s School of Life Sciences tried at least three times over a two-month period to replicate the findings using DNA and NgAgo plasmid, or with a reagent provided by Han, according to Zhou Yuexin, a doctoral candidate at the school. All attempts failed, she said.

In a letter to the editor published by the journal Protein & Cell in November, a group of leading, mainly Chinese scientists from 20 labs around the country raised doubts about the Han team’s study. They all acknowledged failing to replicate Han’s results, adding that the failures could not have been caused by cell contamination.

A Caixin reporter traveled to the university in the northern city of Shijiazhuang for a tour of the Han team’s lab. It was notable that most researchers on site seemed to be violating the lab’s dress code by wearing shorts, casual skirts and T-shirts. One student was seen using equipment without gloves, while another was apparently violating a rule against eating on site. A waste can was filled with empty meal boxes.

Kang Youwei, a doctoral candidate studying biological science at the University of Hong Kong, said samples or specimens are prone to contamination in labs unless workers wear clean lab coats and gloves. “At any standard lab,” he said, “workers are definitely not allowed to do tests and other office chores in the same room or area.”

But questions about work habits inside the lab pale in significance when compared with the issue of sharing data with other scientists, said Zhou of Peking University. “If Han Chunyu would open his original data to the public, all doubts will be cleared up.”

Shortly after Han’s team retracted the academic paper, a statement on the Hebei University of Science and Technology website announced a pending review of the research.

The university said Han had agreed to conduct another experiment that will seek to replicate the earlier study while under the supervision of an independent lab’s researchers. Afterward, the results were to be made public.

The university should move quickly to settle the controversy, said Xiong Bingqi, deputy director at the 21st Century Education Research Institute, as any delay could fuel more skepticism about the scientific community in China.

Contact reporter Li Rongde (rongdeli@caixin.com)

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR