KFC Still ‘Finger Lickin' Good’ in China

He’s been called many things over the years, including “Finger lickin’ good” by admirers and “greasy” by detractors. But “revolutionary” is one of the last words that springs to mind when describing Colonel Harland Sanders, the grandfatherly founder of Kentucky Fried Chicken, now known as KFC.

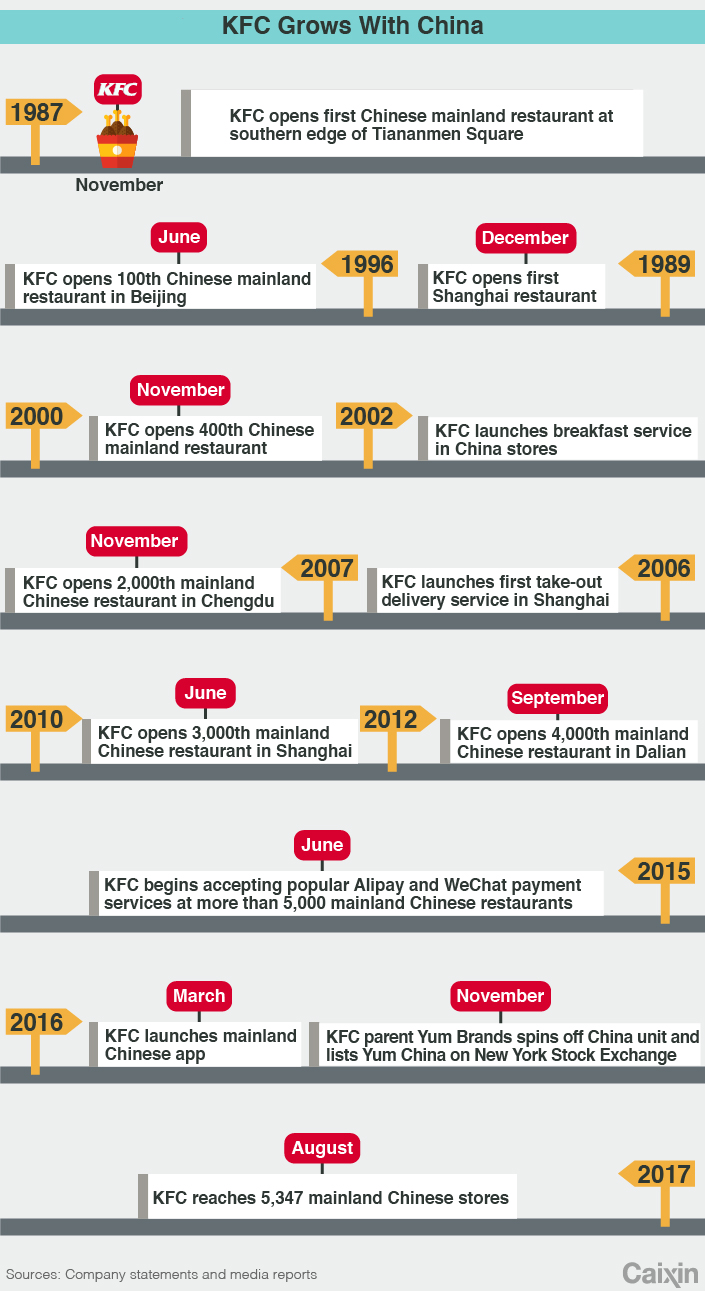

While he might politely decline a moniker that seems more suited to Mao Zedong or Che Guevara, Sanders and the empire he began will almost certainly go down in Chinese history books as revolutionaries for how they changed the modern Chinese dining scene. KFC walked into a relative culinary desert three decades ago when it became the first foreign restaurant operator to sample the China market with its opening of a massive restaurant at the southern edge of Tiananmen Square.

As that restaurant and the chain celebrate their 30th anniversary this Sunday, KFC faces a future peppered with an entire new set of challenges. No longer are matters like finding qualified employees or suitable food suppliers issues, attesting to the huge changes that have taken place in China over the last three decades. Instead, the company faces an uncertain future due to growing competition from homegrown rivals, as well as changing consumer tastes that are swinging towards more upscale, nutritious options.

“Regarded as the earliest entrant, KFC has been one of the most important players and a giant in China’s fast-food market,” said Shirley Lu, a consultant at Euromonitor International. “KFC played a vital role in consumer education at the very beginning, as a result, largely increasing Chinese consumers’ acceptance toward not only fast food but also all kinds of Western-style food.”

|

In 1990, customers line up outside the first KFC restaurant in China. Photo: KFC |

Thanks in no small part to its early entry to the market, including its status as the first Western chain on the Chinese mainland, KFC has grown to become the country’s largest fast-food operator. It had 5,347 stores as of August, and has detailed lofty plans to triple the number of stores for all of Yum China’s brands over the next decade or two.

Alien landscape

The landscape was far different when KFC first came to China in the 1980s to explore opening its first store. The China of that time was just embarking into its reform era, and no major Western restaurant operators had entered the market. Western food was only available at a handful of joint venture restaurants that were off-limits to most Chinese, and concepts like friendly service, food safety and consistent quality standards were equally foreign ideas to most in the local food and beverage industry.

Thirty years ago, current KFC Beijing General Manager Zhao Li was just graduating from high school in the summer of 1987 when she saw an ad in a local newspaper looking for employees for the new store. Back then few people worked at foreign companies, and most were simply assigned to the big state-owned enterprises that were the main employers of the time.

|

A crowd gathers outside a KFC restaurant offering promotions for Children’s Day in 1991. Photo: KFC |

From there she and other new employees attended a boot camp, where they were trained in the chain’s seven steps of customer service. Those included such basics as greeting and looking at customers while taking orders, repeating the order to avoid mistakes and taking a customer’s money with two hands — basic concepts for Westerners but foreign in China’s “Iron Rice Bowl” of that era, where workers were guaranteed cradle-to-grave employment regardless of how they performed.

“It was one thing to learn it, but another to do it,” recalled Zhao, now in her 40s, who would go on to rise through the KFC food chain to reach her current position. “It was easy to get nervous. … The customers were a little surprised when we would welcome them into the store.”

Zhao and other early visitors to the original KFC recalled how long lines snaked outside the store in its early months, and the difficulties many people faced in figuring out alien concepts like how to order at a takeaway counter and to eat without chopsticks. There were also similarly alien prices, which averaged around 20 yuan for a meal in those days, or about $3 at current exchange rates. At a time when most people made 100 yuan per month or less, those kinds of prices were out of most people’s range.

Impressive service

Beijinger Pan Pei recalled how he was making around 500 yuan per month at that time as a freelance tour guide during his college years, an enviable position closed to most. After hearing about the restaurant, he went over one day shortly after the opening to test out the fare, which was then limited to fried chicken, mashed potatoes, coleslaw, biscuits and a few soft drinks and beer.

“We had to wait in line but not too long,” he recalled. “I don’t like greasy food, so I was a little disappointed. My deepest impression was that at that time Chinese restaurants were very backward, they had bad service and you often had to wait a long time. But at KFC we just had to wait two minutes.”

Another Beijing resident Hu Yilun was more typical of the millions of local people who wouldn’t enter KFC until years later, kept away in the early days by high prices. “It was just a distant concept to us, like buying a Bentley car would be now,” he said.

Fast forward to the present when KFC has truly become food for the masses, and Chinese palettes are far more sophisticated than those of the 1980s. The KFC of recent years has suffered from a series of minor scandals involving food safety, mostly related to its suppliers. It has also largely fallen out of vogue among the nation’s droves of newly minted young office workers, who have far more choices than people 30 years ago. Attempting to change that, the company has embarked on a major image and product overhaul, including the addition of higher-end coffee and food, as well as high-tech touches like in-store Wi-Fi.

Those efforts have borne some fruit, as the chain recently returned to same-store sales growth after a period of steady declines. But the road ahead could still be challenging in China’s massive restaurant market of today, where fast-food accounts for about one-third of the 3 trillion yuan in annual sales, said Huang Xiaobin, CEO of catering consulting firm Bestown.

“Their challenges are pretty big now because there are many Chinese rivals, most offering Chinese food choices. So they’ve taken a lot of KFC’s market share,” he said. “Chinese traditional eating habits are also getting more and more emphasis. Many of us look at their nutrition; many people think it’s very greasy and not nutritious. Many parents don’t let their children go to KFC anymore.”

|

- 1Cover Story: China Carves Out a Narrow Path for Offshore Asset Tokenization

- 2Drownings Shake Chinese Enthusiasm for Travel to Russia

- 3Over Half of China’s Provinces Cut Revenue Targets

- 4Li Ka-Shing’s Port Empire Hit by Forced Takeover Amid Panama Legal Dispute

- 5In Depth: China’s Mutual Fund Industry Faces Overhaul After a Banner 2025

- 1Power To The People: Pintec Serves A Booming Consumer Class

- 2Largest hotel group in Europe accepts UnionPay

- 3UnionPay mobile QuickPass debuts in Hong Kong

- 4UnionPay International launches premium catering privilege U Dining Collection

- 5UnionPay International’s U Plan has covered over 1600 stores overseas