‘Simply Kicked Out’: How Village Committees Deprive Women of Their Land Rights

Women may hold up half the sky in China, but when it comes to land, it’s a totally different matter.

As the country’s arable land shrinks and rural property values surge, women are being robbed of their rights by the village committees who allocate and manage land.

Women are suffering from double discrimination at the hands of these committees that are elected by local residents. In many places, women who marry outsiders have their claim to land in their birthplace revoked, even when the land certificates still bear their names. Those who move to their husband's villages are often refused recognition and the right to any claim on their spouse's land.

“A married daughter is like spilled water,” said Ma Fengling*, who has waged a court battle since 2014 to have her land rights reinstated. “This is such a common and deeply rooted view that they would never give anything to us married women, who are simply kicked out.”

Ma runs a two-story inn with her husband in downtown Zengcheng, a suburb of China’s southern industrial hub Guangzhou. Although her new home is just 7 kilometers (4.3 miles) from her birthplace, and both she and her son have her village address in their household registration documents, the village committee decided that she was “no longer a village member” and forced her to give up her land after she married in 2011.

Her name is still on the land contract certificate issued for their family plot of about 0.13 acres, which was collectively held by Ma, her parents and her brother. The certificate entitled her to use or lease out her land to a third-party for a payment, but forbade her from selling the plot. But the village committee decided to overlook this legally-binding document.

|

A farmer holding a land contract certificate. President Xi Jinping announced at the recent National Party Congress that rural residents would have the right to use their land for another 30 years after current contracts expire over the next decade. Photo: Visual China |

This discrimination, which is being carried out in spite of national laws that ban such actions, has dealt an economic blow to thousands of rural households. Women like Ma are excluded from payouts amounting to thousands of U.S. dollars when their land is expropriated for property or infrastructure development projects.

But there is also something much bigger at stake. Rural land is the fall-back option for millions in China’s countryside, who don't enjoy the same access to health insurance or pensions enjoyed by landless urban dwellers. Women who lose their claim to land in their birthplace and their husband’s home have no safety net when they are widowed or divorced.

Village committees, under pressure to allocate limited land stocks to a growing number of village members, have found it “convenient” to revoke land from women who move out after marriage and refuse to recognize those who marry into the village. Deeply entrenched notions of male superiority have meant some village collectives even ignore court orders banning such moves.

Therefore Ma’s case isn’t isolated. At least 82 other women in Zengcheng district alone have petitioned the local government or gone to court after village committees decided to revoke their land rights between 2014 and 2016, according to Ma’s lawyer Lin Lixia.

China’s top legislative body is currently deliberating an amendment to the law on contracting rural land to plug these loopholes. The draft law, which was open for public comment until early December, says “names of all members of a household with contracting rights” should be added to the land certificates. But, it has left it to provincial-level or district governments to interpret who qualifies for such rights, which has led to inconsistencies.

The law is also vague when it comes to dealing with another major flashpoint — the relative autonomy that allows village committees to arbitrarily decide whether to include women who were married off, new brides or divorcees, based on “local customs” instead of national laws. The amendment says the “principles” used to determine who qualifies as a village member — a crucial factor that underpins access to land — “shall be subject to national laws and regulations.” But some experts say this doesn’t go far enough to rein in the powers of village committees.

In Ma’s case, her village committee refused to recognize her as a “member of the cooperative” after her marriage, saying she hadn’t “fulfilled her obligations as a villager,” without presenting any evidence to support this claim.

“I still pay for public cleaning and waste disposal services. I have even voted to choose members of the village committee and the director. How could I cast my vote if I were not a village member?” said Ma.

Provinces including Guangdong are testing the idea of allowing villagers to lease their smallholdings to agribusinesses or more professional farming co-ops that could increase yields, but Ma has lost her chance to turn her portion of land into equity, and get an “annual dividend and a bonus,” in accordance with annual yields.

The annual dividend for about 0.17 acres of land in her village is about 5,000 yuan ($755). Ma says she could have personally earned about 1,000 yuan per year, the same amount her parents and brother received from renting their collectively held plot.

“I didn't pay much attention to the dividends, because it’s a small amount, compared to what I can make with my business," said Ma. “Also, my father and brother live in the village, and they handle these matters. Land-related issues are generally decided by men in the house. It is common in villages; most families have this tradition.”

She was only pushed to take matters into her own hands when she realized that she might suffer a much bigger loss.

The government expropriated village land for a real estate and tourism project in 2013 and announced a compensation plan for villagers. According to official expropriation documents, all village members held similar-sized land parcels and could receive 127,000 yuan per person in compensation. But the list of names for those entitled for payouts excluded women who had married outside the village.

Ma petitioned the local government in Licheng, a subdistrict of Zengcheng, to invalidate the village ruling and reinstate her membership and rights to land in 2014. But the government did not support her claim, saying she no longer lived in the village. It also echoed the village committee’s assessment that she hadn’t fulfilled “certain obligations necessary for someone living the village,” without specifying what these were, according to official records on how her complaints were handled.

The local administrative body also put the burden of proof on Ma and asked her to produce the “written laws” used by the village committee to revoke her land rights. But the committee terminated Ma’s membership in accordance with villagers’ verbally-agreed upon customs.

Ma sued the subdistrict government in the district court in December 2015. The court then ruled the local government’s decision had no legal basis, and ordered them to cancel it and have another hearing. But that didn’t put an end to Ma’s troubles.

The Licheng government appealed against the verdict to the Guangzhou Railway Transportation Intermediate Court. The higher court also upheld the district court’s judgment in 2015, in accordance with the country’s law on the Protection of Rights and Interests of Women and other supporting provisions, which clearly state that women enjoy equal rights to land as all other rural cooperative members regardless of a change in marital status.

But the local administration chose to ignore the court order. Two months after the verdict, the Licheng government reissued a decision as per the court’s request, but continued to not recognize Ma as a “cooperative member,” arguing “the village has provided evidence to show Ma didn’t fulfill her obligations as a villager.” But again, both the village committee and the subdistrict government did so without presenting any evidence.

“They are playing with words,” said Peng, a judge from the Guangzhou Railway Transportation Intermediate Court who only gave his surname. “We have no ability to make a decision and order the authorities to issue it. Judicial power cannot dominate the administrative organs.”

“But how can administrative bodies be above the law?” asked Lin Lixia, Ma’s legal aid lawyer who has devoted more than a decade to women’s rights protection.

“A dead mouse doesn’t feel cold,” quipped in Lü Xiaoquan, deputy director of the Qianqian Law Firm, which handles Ma’s case. “It is obvious that they hold judicial authority in contempt.”

Officials from the Licheng subdistrict government and Ma’s village committee declined Caixin’s request for an interview.

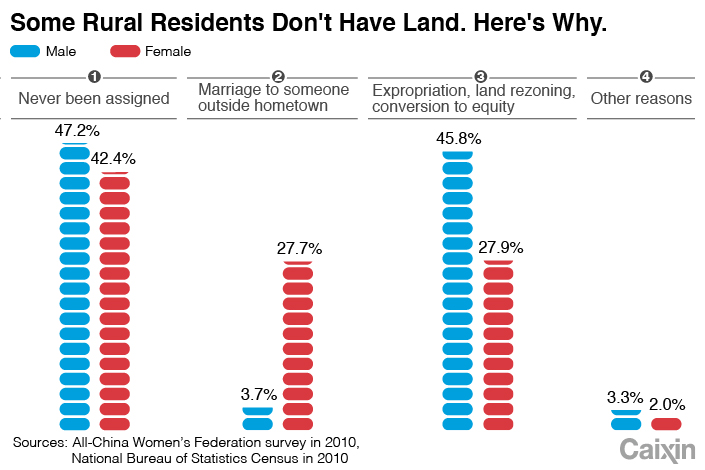

The last national survey on women’s land use rights conducted by the All-China Women’s Federation in 2010, found that 21 % of rural women didn’t have land, and the figure had more than doubled compared to a decade earlier. Some 27.7 % among those who have lost their land said a change in marital status, had led to the loss of land use rights.

|

The proposed amendment to the rural land law is an attempt to rectify flaws before the upcoming renewals in ten years’ time. It came two weeks after President Xi Jinping announced, at the recent National Party Congress, that rural residents would have the right to use their land for another 30 years after current contracts expire.

But there is no timeline on when the amendment will be passed or come into effect. Ma isn’t sure whether the proposed amendments will push her village committee to reevaluate her case.

“If not, I may lose my land forever!” she said.

Chinese villages develop their own rules to govern their daily operations, and are granted a certain degree of autonomy by the central government to decide on important internal affairs through a villager assembly, based on the National Organic Law on Villagers’ Committees. This autonomy, at times, have allowed them to ignore national laws, including an important amendment to the rural land law in 2003, which clearly says a woman’s birthplace cannot take her land away if she hasn’t acquired land use rights for the plot owned by her husband’s family.

Aside from ingrained gender biases, a scarcity of rural land, especially in some densely-populated areas, have made local governments and village committees reluctant to acknowledge female villagers’ rights, because it threatens to dilute the landholdings of everyone else.

“Our village already has very little farmland. It is impossible, therefore, to let those married-off women and their new family to register their residency here and lay claim to our already limited land resources,” said You, director of the village committee of Baizhi in Hebei province, who only gave his surname.

|

China launched a land registration system in 2014, seeking to document over a billion plots assigned to rural households over a period of four years.

But a survey in three provinces in the central China last year found that 1 in 5 women who had already “lost” their lands don’t have their name included in any land documents from her parent’s side or her husband’s side.

Cui Jianhua*, from Harqin Banner in Inner Mongolia, is one of them. She grew medicinal herbs on the approximately 0.33-acres of land given to her husband’s family. Cui’s birthplace had taken back her contracted land after her marriage in 1990.

But she also ran into trouble when trying to add her name to her husband’s land contract, which would give the couple access to more land.

The village convened an assembly to check the existing contracts and discuss the rules of renewal. Some families with members who had married off or died were unwilling to give up their land, and thus, absent from the meeting, and the new arrangement to allocate land to women who had married into the village like Cui could not be passed without the consent of the majority.

“Land is everything for us farmers,” said Cui. “But the village committee just said they were unable to help.”

The couple had little choice but to pay 8,000 yuan a year to lease another 1.65 acres of land from other villagers for farming, so that they could eke out a living and send their two daughters to college.

To save money for the lease, Cui, 49, doesn’t hire any helpers even at the busiest times. She and her husband had to work for over 20 hours per day for nearly two and a half of months during the harvesting season.

‘Tyranny of the majority’

Village committees involved in land right disputes argued rural land contracting is a collective concern and closely related to all members’ interests, and thus, should be decided by all villagers.

Several policymakers and lawyers, however, argue issues concerning individual’s human rights and interests should not be decided by majority voting. Matters which require majority consent should only refer to villages’ public affairs such as its budget and other collective economic activities, they said.

“The power and autonomy of village committees should be further defined in particular issues to avoid a so-called tyranny of the majority upon women’s rights,” said Chen Xiurong, a lawmaker familiar with the draft amendment.

“Some local governments may turn a blind eye, as they are reliant to some extent on the partnership with village committees to carry out their work smoothly,” according to Xu Weihua, who formerly handled public calls and letters at the state-backed All-China Women’s Federation.

Xu and Ma’s lawyer Lin said there was an urgent need to develop a land contracting system that takes into account changes in marital status, employment and resident registration. They say contracting rights of farmer’s sons or daughters with secure jobs in the civil service or academia should be withdrawn, to ensure a fairer allocation of resource.

An official assessment system that has particular checks and oversight on those who received complaints or got involved in administrative litigations could help judicial enforcement, according to Li Huiying, a top women researcher of the Communist Party School.

But ingrained cultural biases can’t be swept away overnight.

A campaign to revise village committee practices is slowly starting to unfold. Two villages in Hebei and another in Henan rewrote their self-governing rules in 2015, adding new articles to protect women’s land rights. Local courts and governments in these places have also issued guidelines to ensure gender equality on land in line with national laws.

Ma’s 6-year-old son started primary school in September. Although she now has more time on her hands, she hesitated on whether to pursue her court case or focus on the family inn that helped her earn about 4,000 yuan a month.

The Guangzhou railway court has issued another enforcement order to the sub district government upon Ma’s request, but she still hasn’t got any feedback. The order would lapse by the end of the year.

The Zengcheng district government said they were investigating and trying to solve the problem, according to Wu Jincheng, director of the district’s justice bureau.

“But, it looks like a fruitless effort. One of my friends appealed five times but still got nothing,” she said. “Maybe I shouldn’t waste my time anymore.”

Note: The women who shared their stories about having their land rights revoked requested to be identified with pseudonyms given the sensitivity of the issue.

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR