Taboo-Busting Professor Who Dared to Teach About HIV Due to Retire

When Central China was ravaged by the rapid spread of HIV in the mid-1990s, local governments initially responded by keeping mum, hoping the problem would just go away.

Journalists, activists and nongovernmental organizations working on the issue were banned from operating in the region or coerced into leaving. Gao Yanning, a professor of public health at Shanghai’s prestigious Fudan University, was one of the few people able to document the impact of the epidemic caused by illicit blood dealers and a government-backed unsanitary blood-for-cash drive in the late 1980s and 1990s.

The revolutionary work done by Gao, who at 60 is set to retire this year, to pioneer China’s understanding of the intersection between gender, sexuality and public health, to de-stigmatize the study of the LGBT community and to raise awareness of China’s HIV situation has inspired college courses around the country. But many now worry about who will keep his legacy alive.

|

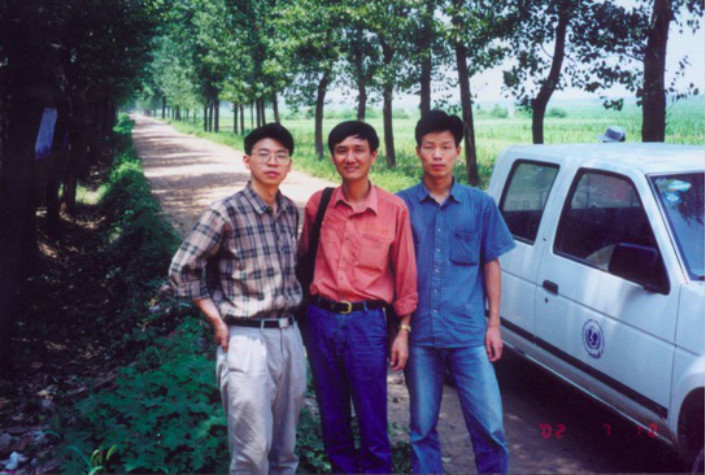

Gao Yanning (middle) in Wangyang in July 2002. Photo: Gao Yanning |

A visit to a Thai university in 1999 to study the social context of AIDS inspired Gao to launch a social science course on the condition the following year. In 2000, he also began to investigate social support in China’s so-called “AIDS villages.”

These “AIDS villages” were a result of the negligent practices of a government-backed paid blood donation network active throughout under-developed Central China during the 1980s and 1990s. Offering about 50 yuan per donation, a significant sum at the time, these centers extracted platelets from drawn blood and then pumped the red blood cells back into the donor. This work was also conducted by illegal private blood dealers, known as “blood heads.”

However, HIV-positive blood was sometimes mixed with donors’ blood during this extraction process, leading people to contract the virus when their red blood cells were returned to their body. So blood-borne diseases spread rapidly among the blood sellers — who passed HIV to their spouses, children, and also to patients who received transfusions made from the blood.

This mixing of blood and the use of unsterile equipment devastated the Central Plains, infecting an estimated 500,000 people in Henan province alone.

Today, activists estimate there are about 1.5 million people living with HIV in China. Despite its implicit role in the spread of the virus, the Chinese government has never accepted responsibility for the blood donation scandal.

When Gao started visiting Wangyang, a Henan village in which many people were living with HIV in June 2002, the government had already banned HIV-related organizations from working in the province and had silenced journalists who reported on the epidemic. The government’s failure to issue accurate information on HIV only reinforced the social stigma of the disease.

|

Gao Yanning (left) with villagers from Wangyang on Jan. 16, 2003. Photo: Gao Yanning |

Gao says the residents of Wangyang “lived like livestock.” One 35-year-old had lost her husband to AIDS just two months before Gao’s first visit. As his group passed the woman and her 10-year-old daughter, “she called out with the last of her strength, ‘Help! Help!” Gao said.

Another villager, an old man, was paralyzed. He was only able to drag himself to and from his door — the path on the floor where the old man moved had been rubbed smooth.

While in the village, he interviewed and photographed villagers, documenting their status. He gave each interviewee a red Fudan University envelope filled with 50 yuan and a business card so they could reach him if they needed help. From 2002 to 2008, Gao made an annual trip to Wangyang, where he would stay for as long as six months collecting information and helping the villagers. All of this was in spite of the government’s efforts to cover up its mistakes and the social taboo about contact with people living with HIV.

Over the years, he recorded thousands of narratives.

|

Undated photo shows Gao Yanning teaching a class at Fudan University in Shanghai. Photo: Gao Yanning |

Born in 1958 in the Guangxi Zhuang autonomous region, Gao grew up “in a new China, raised under the red flag.” His experiences coming of age during the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) informed his commitment to treating everyone equally, regardless of gender, sexuality, health or social status.

His fate was tightly entangled with the events that he lived to see, such as political persecution, having to labor in remote areas and the resumption of the university entrance examination after a years-long hiatus. He said that “it is impossible for me to turn a blind eye to the AIDS villages.”

Walking home from school one day, Gao recalls seeing a group of people shouting communist slogans at a man in a pig cage as they tossed him in the river.

“The cage was locked but he ended up escaping, surfaced and swam towards the other bank of the river with his feet bound together. Two militiamen shot at him and I saw him drown slowly, with the water becoming red with his blood. “Decades later, Gao is still shaken by the injustice, asking “how can people be treated like this?”

At the age of 14, he dropped out of school and did some odd jobs such as digging dust and drying fruit pulp for a pittance. His father could hear his sighs at night, as he aspired to go back to school. Finally, the old headmaster of his secondary school allowed him back and he was able to start high school a year later.

|

The last time Gao Yanning visited Wangyang was on July 12, 2008. Photo: Gao Yanning |

Gao took the university entrance exams in 1977, the first time they were held in 11 years, and got into the Guangxi Medical College Department of Health.

Freeing minds

After visiting the AIDS villages, Gao returned to Fudan and began teaching public health courses on AIDS and health issues affecting the gay community, among others. These courses focused on marginalized and disadvantaged groups, laying emphasis on the theory and practice of sex and gender. His first course, “Gay Health and Social Science,” preceded even the World Health Organization’s 2006 program to mainstream gender issues in public health curricula.

Despite the stuttering progress of LGBT advocacy in China at the time, Gao spoke widely and avidly about homosexuality, transvestitism, prostitutes and AIDS in the context of public health. He also invited famous scholars to Fudan to give lectures. The scholars included Li Yinhe, a prominent sexologist and LGBT rights advocate; Pan Suiming, honorary director of Renmin University’s Institute for Research on Sexuality and Gender; Zhang Beichuan, sexologist and noted ethnographer of gay men in China; and Bai Xiangyong, a fiction writer from Taiwan.

In addition to lectures, Gao took his students to gay bars, parks, dance halls and other places for field research. These trips, Gao hoped, would free their minds from discrimination and prejudice. Additionally, he hoped that the medical students might be able to establish a connection between behavior and medical phenomena — enabling them to focus on prevention and not just treatment. The implications of this, he claims, can be applied to other marginalized groups as well.

During the first two years he offered the course, Gao had only one student, then enrolment jumped to four in 2003. When Gao did an informal survey to find out why his class was so “unpopular” some students complained about the credit offered and remote location of the lecture hall, but many later admitted that it was the stigma of being formally associated with anything “gay” that kept them away.

Some of Gao’s former students have said that it was his class that led them to think that “doctors should do more than ‘prescribe’ treatment, and philanthropic concern for patients is necessary.”

Now, Gao Yanning is only teaching one course, on promoting health in marginalized groups. “In my position as professor, I’ve already done my best,” he said.

However, his colleagues and students worry that no one will fill the gap left by his retirement.

Zhang Beichuan, one of the first scholars on large-scale AIDS prevention in China and the first winner of the Barry & Martin Prize in 2000, a prize awarded to those who have done exceptional work in AIDS prevention, treatment and care, said that “once [Gao] leaves, the sound of the piano he plays may disappear.”

Zhou Dan, Shanghai’s first openly gay lawyer, said much the same thing. “After Professor Gao retires, what are we to do? I want to know, who will research gender studies and AIDS research in a scientific way at Chinese universities?” Zhou said.

Gao’s biggest concern, however, is that the AIDS problem in rural China has not yet been resolved. “I feel powerless.”

He feels that the world has forgotten the villagers. “Every story is so painful and so unjust. Those who listen, can’t listen [to the stories], and those who see, can’t see [the pain],” and now “everything is back to calm, quiet, so quiet that people believe that this has really never happened.”

Now, most of the people living with HIV in Henan receive free medication from the government, and their living conditions have greatly improved. But Gao doesn’t feel justice has been served. In 2016 he began writing a book about the Henan blood disaster, one of a few ever written. He wants to dedicate his book to the AIDS villagers, the “children who have grown up or who never grew up.”

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR