Fintech Focus: The Fall of Peer-to-Peer Lending in China

Since the start of 2016, China’s online peer-to-peer (P2P) lending and microloan industry has been significantly changed due to a slew of sweeping rules released to curb the risks of the booming sector.

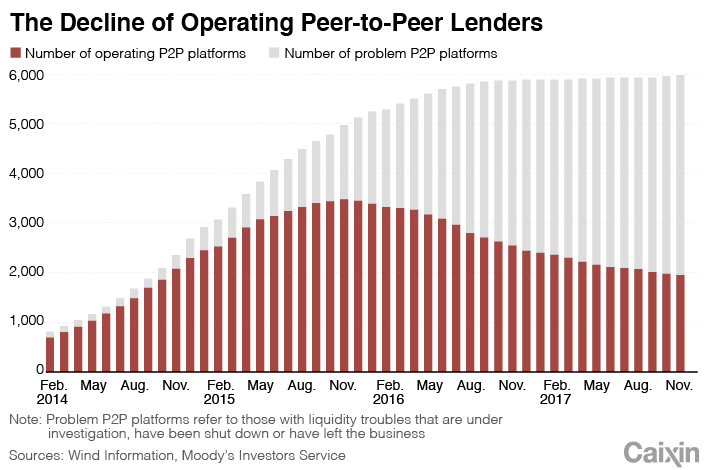

P2P lending, which was designed to bypass traditional lending by matching individual borrowers and lenders, began to flourish on the Chinese mainland in 2011 as the government encouraged the wider use of technology to expand financial services to small businesses and individuals. At P2P lending’s peak in late 2015, there were more than 3,300 platforms operating, according to Wandaizhijia, a portal site that tracks the sector.

However, due to the absence of unified regulations, a great proportion of P2P lenders began collecting cash from investors, offering high returns. A market worth more than 1 trillion yuan ($158 billion) quickly developed. These companies then lent out that money to businesses such as property developers. Some did what they were supposed to do and made a profit. However, others got into trouble when some of their loans soured, leaving them unable to generate the returns necessary to pay investors. Still others spent their amassed cash on their own executives. Many P2P companies failed, and cases of fraud surged.

There were several high-profile cases of P2P companies whose businesses turned out to be Ponzi schemes. In December 2015, authorities shut down Ezubo, one of the country’s largest P2P players at that time, raising the curtain on a national campaign to scour swindlers from the industry. Authorities later found that Ezubo bilked 900,000 investors across China out of more than 50 billion yuan.

In August 2016, authorities reiterated that a P2P lending platform must serve only as an intermediary agent and information provider for investors and borrowers, according to a document released by the banking regulator and three other government agencies.

The rules banned the P2P companies from raising funds or guaranteeing any loans made on their platforms. Authorities set lending and borrowing caps for individual accounts on the platforms. They also required P2P operators to strengthen management over their investors’ funds by hiring a custodian bank to hold the money.

Since the new regulations took effect, the number of operating P2P platforms has fallen from more than 3,383 at its peak in January 2016 to 1,883 by the end of March 2018, according to data compiled by Wangdaizhijia.

|

Some of China’s P2P platforms responded to the new regulations by getting out of the P2P lending game. Dubbing themselves “microlenders,” some companies changes their business to offering “cash loans,” which are small, short-term, unsecured consumer loans with annual interest rates that can exceed 1,000% in extreme cases.

It wasn’t long before there was a boom in consumers loans with usurious interest rates, followed by reports of borrowers being confronted by intimidating and sometimes violent debt collectors. The situation eventually caught the attention of regulators.

In April 2017, the central bank and the banking regulators responded with new policies to curb risks in the burgeoning online microlending market and in other unregulated lending activities. The new policies, which covered both microlenders and P2P platforms dealing in cash loans, put a statutory 36% limit on a loan’s annual percentage rate, which consists of the total interest rate and fees charged to borrowers each year. The new policies also outlawed unlicensed lending platforms.

In a detailed guidelines released in December, regulators said it would suspend issuing licenses for new microloan companies, and shut down unlicensed microlenders.

After the new rules took effect, some companies shelved plans to expand into the microlending business. Meanwhile, existing lenders are considering a shift to other businesses.

One example is online microlender Qudian Inc., which raised $900 million in October in what turned out to be the largest listing of the year in New York by a Chinese fintech company. Amid the clampdown on microlending, Qudian moved into the auto financing business.

A Qudian representative told Caixin that it made the decision so it could re-engage users by offering them a new way to buy big-ticket items by allowing them to gradually pay off their purchases through installments.

Also in December, authorities began to squeeze microlender funding. Regulators banned microlenders from raising funds through asset-backed securities (ABSs), and later banned banks and other financial institutions from funding microlenders by buying structured products backed by future payments on their loans.

The move hit the heavyweight Ant Financial Services Group the hardest. By the end of last year, two of its microlending units, Huabei and Jiebei, had issued 70% of the 394 billion yuan in total outstanding microloan-backed ABSs traded on China’s interbank market, according to data from Wind Infomation.

The situation forced Ant Financial to tap other sources of funding. Alibaba Group Holding Ltd., the e-commerce kingpin controlled by the same founder, Jack Ma, bought a stake in Ant Financial.

The tightening regulatory environment has taken a toll on U.S.-listed Chinese microlenders. In the three months through December, China Rapid Finance Ltd., the second Chinese microlender that floated shares in the U.S., reported a loss of $3.3 million in the fourth quarter.

Listing plans have also been delayed. The initial public offering plan of Lufax, an online wealth management spinoff of the country’s second-largest insurer, Ping An Group, was postponed after the company’s senior managers hinted at an April listing date. Instead, Jessica Tan, the company’s deputy CEO, told reporters in March that the company will take Lufax public only when the time is right.

Contact reporter Leng Cheng (chengleng@caixin.com)

- 1Cover Story: China Carves Out a Narrow Path for Offshore Asset Tokenization

- 2Drownings Shake Chinese Enthusiasm for Travel to Russia

- 3China Business Uncovered Podcast: A $15 Billion Bitcoin Seizure and the Fall of a Cybercrime Kingpin

- 4Over Half of China’s Provinces Cut Revenue Targets

- 5Li Ka-Shing’s Port Empire Hit by Forced Takeover Amid Panama Legal Dispute

- 1Power To The People: Pintec Serves A Booming Consumer Class

- 2Largest hotel group in Europe accepts UnionPay

- 3UnionPay mobile QuickPass debuts in Hong Kong

- 4UnionPay International launches premium catering privilege U Dining Collection

- 5UnionPay International’s U Plan has covered over 1600 stores overseas