In Depth: Coronavirus Just the Latest Hurdle to Local Government’s Chipmaking Dreams

Local governments around China were investing billions of yuan in chipmaking projects, heeding the central government’s call for the country to reduce its reliance on imports of the crucial technology.

Then came Covid-19, the ongoing epidemic that has killed thousands and disrupted supply chains across China and the world. The outbreak has had an untold impact on the local and global economies, including on the semiconductor sector where it has created workforce and supply issues.

But even before the virus struck, cities across China were finding that their pockets were simply not deep enough to build a competitive chipmaking industry from scratch, despite stretching their budgets to the breaking point.

China’s coronavirus woes will eventually pass. Analysts say there will be no shortage of resources pumped into chipmaking industry by Beijing to get it back on its feet. But those with intimate knowledge of the key strategic sector say a more coordinated national strategy is needed to make the dream of chip self-reliance a reality, in part by preventing local governments from competing with each other for the same slice of the pie.

Though the chipmaking sector has gained added significance since the U.S. began placing major Chinese tech firms on an export blacklist early last year, Beijing began encouraging its development as far back as 2000, issuing a set of national guidelines in 2014.

Since then, over 50 large-scale semiconductor projects have sprung up nationwide, with total pledged investment reaching 1.7 trillion yuan ($248 billion) according to Caixin’s calculations.

|

Coronavirus disruptions

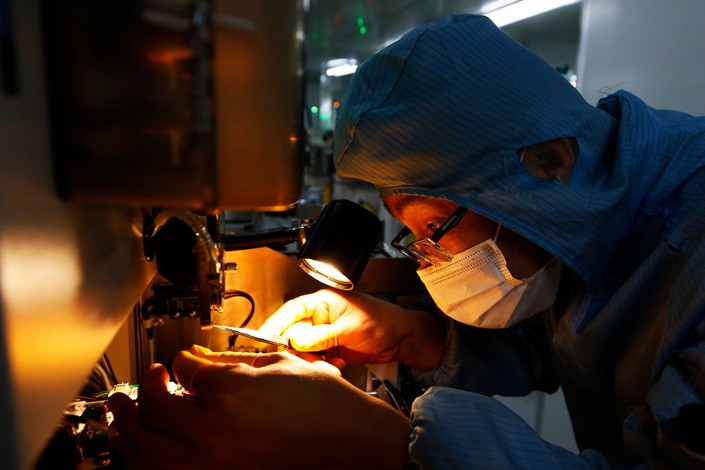

Since the coronavirus outbreak spread nationwide in January, businesses in many sectors have grappled with staffing issues due to mandated quarantines and travel restrictions. The semiconductor sector isn’t immune, and companies further down the supply chain involved in packaging and assembly have been the hardest hit, analysts said.

These areas are more vulnerable than those further up the supply chain, such as manufacturing and design, as they are more labor-intensive, said Sheng Linghai, a semiconductor analyst at research and advisory firm Gartner. However, though manufacturing has a relatively high degree of automation, manufacturers still face the risk of overworking the limited number of employees who have returned to the job, Sheng said.

Also, further issues could be posed by the spread of the coronavirus epidemic to Japan, a key supplier of raw materials for Chinese chipmakers, said Chris Hsu, an analyst with market researcher Trendforce. “The coronavirus epidemic has severely hampered domestic production of consumer products that use chips, and has also severely impacted the development of some other related industries at a global level,” Xu said.

Still, analysts said the coronavirus’s impact on chip investment will prove temporary as Beijing will continue plowing resources into the sector’s development.

“As far as we can tell, there aren’t any government investment plans affected by the coronavirus yet,” said Jeter Teo, another analyst with Trendforce. “Though some projects are yet to restart business due to coronavirus disruption, the situation is still manageable.”

Huaian’s floundering ambition

East China’s Jiangsu province has in recent years joined the race to develop chips with particular fervor.

Even its poorest city by total GDP, Huaian, has jumped on board with a project to make image sensor chips, known as CIS chips, with planned investment amounting to 45 billion yuan. However the project, incorporated as Dezhun Semiconductor Ltd., has been put on hold after struggling to scale up production and running out of cash.

Dezhun was headed by Xia Shaozeng, an industry veteran who previously worked at Taiwan’s Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp. (SMIC), a leading global chipmaker.

Even though Dezhun was designed as a joint venture between the Huaian government and Xia, most of the cash spent so far has come from the public purse, in particular the city’s suburban Huaiyin district. Huaiyin’s generous 2.6 billion yuan investment in the project was worth a bit more than its fiscal income that year.

Dezhun set up a factory in June 2017, but as of October its total sales revenue has amounted to just 250 million yuan. Most of the 4.5 billion yuan already spent on the project went to construction, equipment and patent licenses.

Despites efforts made by Huaian and Xia, it has proven difficult to generate private sector interest in investing in Dezhun. As a shortage of cash continued to constrain the project’s production capacity, the local government ultimately decided it couldn’t afford to support the project any longer and it has been mothballed.

Underestimating the challenges

Huaian is just one of dozens of local governments that have jumped headfirst into the sector.

At least 15 projects aiming to make chips in areas ranging from processing to storage were announced last year in East China’s Shandong province, mostly in its capital Jinan. However, many have faced the same fate as Dezhun, being put on hold after the cash run out. Another example is the 17 billion yuan Dekema project in Jiangsu’s provincial capital Nanjing, just 200 kilometers (124 miles) south of Huaian.

Investors and company executives said that many of these enthusiastic local governments underestimate the huge difficulties — and capital requirements — of setting up a chip industry, and overestimate their ability to attract private investment.

“Building a factory in the first place could cost tens of billions of yuan, and tens of billions of yuan more for research,” said a high-level executive at a Chinese semiconductor company, who added they were not surprised to see projects like Dezhun suspended.

There were several aspects of Huaian’s bet that made sense. The chips Dezhun intended to make, CIS chips, are a key part of cameras and their market is expected to grow from $15.5 billion to $21.5 billion, according to IDC Insight.

It also looked well poised to tap into the sector — it had exclusively licensed patents from sector leader ON Semiconductor and a team of experienced engineers poached from Xia’s former employer, SMIC. Also, Huaian secured all the necessary production licenses from regulators in Beijing, according to a Huaian government official.

Still, none of this was enough to surmount the shortage of cash. “Huaian’s government underestimated the spending needed for a chip business and it just couldn’t afford to do it,” said a manager of a state-owned investment fund that focuses on semiconductor projects.

Resources spread thin

Besides setting up a business from scratch, another approach taken by some governments has been to invite existing companies to set up shop in their area. Besides offering these companies direct funding, they tend to offer a package of preferential policies such as free land and tax breaks.

However, fierce competition between cities fighting over a few leading firms can lead to excess capacity and resources being spread too thinly, Jiang Guangzhi, an official at Beijing municipality’s Bureau of Economy and Information Technology (BEIT), said at an industry forum in September.

A lot of these projects target the lower end of the supply chain. This has created a situation in which China is projected to have around 20% of the world’s total semiconductor wafer production capacity by the end of this year — according to a 2016 report by the U.S.-based industry association Semiconductor Equipment and Materials International — while its technology is at least two generations behind overseas peers, according to industry experts.

“Local governments are now scrambling for projects of chips at the lower end of the supply chain. However, demand is limited for such chips. This is potentially a huge risk for China in future,” said Chen Kai, a researcher at Shenzhen-based Jiye Changqing Economics Institute.

Coordinated strategies

China’s state-led effort for chip business did produce some rather successful projects that could serve as models. One is ChangXin Memory Technologies Inc., which was founded in Hefei, the capital of East China’s Anhui province, in 2016 and was funded by the local government.

ChangXin has bested many of its domestic peers simply by getting mass production up and running. Its also expected to deliver its first locally designed DRAM chip by the end of this year.

ChangXin makes DRAM, one of two major types of memory chips, which are commonly used in personal computers and servers. The company, which operates a $8 billion facility in Hefei, was expected to quadruple production of DRAM chips to 40,000 wafers a month, or 3% of global output, according to a report by the Nikkei Asian Review.

Still, promising projects like ChangXin are few and far between. Industry experts said local governments rushing into semiconductor projects without a coordinated strategy from the central government, for example limiting the number of production licenses that are issued, could actually hurt the industry’s development.

When different local governments are competing to attract the same company, the result could be that resources are spread too thin, said an executive at a state-owned chipmaker. It also leads to companies being distracted, said the BEIT’s Jiang, adding that, in some cases, companies’ operational resources can be divided as they try to take advantage of many different government programs at once.

Yang Fenglin, vice manager of Shanghai-based startup Panchip Microelectronics Co. Ltd., advised cities to target projects that compliment their existing industrial advantages.

Yang gave the example of Wuhu in Anhui, a city known for its automobile manufacturing capability. Yang said the city could focus on developing chips that are used in automobiles to make the industry into a “closed loop.”

An industry expert who asked not to be named said Beijing should enhance its oversight of the chipmaking business, and if a planned project’s prospects seem dim, the central government should not hesitate to veto it.

“The semiconductor industry is hot in China, but there is a long way to go,” he said.

Contact reporter Mo Yelin (yelinmo@caixin.com) and editor Joshua Dummer (joshuadummer@caixin.com)

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR