Weekend Long Read: Remembering the People’s Republic’s Early American Friends

Editor’s note: Zi Zhongyun (资中筠) is a historian and an expert on U.S. studies with the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences. In a memoir published at her 90th birthday in 2019, Zi recounted her eventful life in one of the moments of most rapid change in China’s history. She sketched profiles of a dozen Americans she encountered in her work at the foreign ministry and in other capacities, including the playwright Arthur Miller and Shirley Du Bois, the wife of writer and civil rights activist W. E. B. Du Bois. Her meeting with these characters took place during a time diplomatic relations between China and the U.S. were beginning to thaw. And those American visitors were a rare sight, reflecting a special point in history.

What follows are translated excerpts from Zi’s book, first published in Chinese at Caixin. The editors have added notes to the text, altered the order of the profiles and edited them for length and clarity.

|

Zi Zhongyun. Photo: VCG |

My work has given me a unique opportunity by putting me in touch with Americans from all walks of life — upper and lower; left, right and middle.

Taking Arthur Miller down a peg

Arthur Miller became popular in China in the 1980s when his play “Death of a Salesman” was performed here.

In the spring of 1978, Miller and his wife visited China for the first time. Because Miller was a well-known playwright, a Chinese writer accompanied Miller and his wife throughout their visit. His name was Qiao Yu, and he had just written a play about Yang Kaihui, the second wife of Mao Zedong. At that time few writers had been “released” (Editor’s note: this refers to being released from confinement or prosecution during the Cultural Revolution (1966-76)) and available to accompany foreign guests. The mental state of Chinese intellectuals who had experienced the Cultural Revolution was completely different from that of Chinese intellectuals nowadays. Qiao was modest, often admitting he knew little about the outside world. In contrast, Miller was quite confident, even though he knew little about China.

In fact, at that time, none of us really understood Miller’s status in the literary world. The Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries had invited Miller based entirely on a political standard, in light of his status as a “progressive American playwright.” His plays, including “Death of a Salesman,” were seen as insightful exposures of the cruelty of the capitalist system. But when it was actually performed in China, people took entirely different understandings away from it. Miller’s China visit was barely covered in the press.

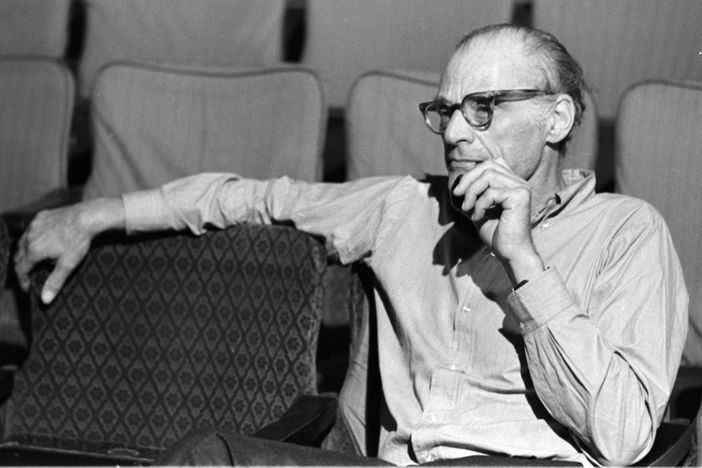

|

Playwright Arthur Miller at a rehearsal for his play “The Creation of the World and Other Business” in 1972. Photo: VCG |

At one point, Miller told me that Chinese writers really lacked knowledge. For example, Qiao didn’t seem to have even heard of Fyodor Dostoevsky. I didn’t agree with Miller. I was certain that Qiao knew of Dostoevsky. Something must have been lost in interpretation. Besides, I was offended by Miller’s condescending attitude. I looked for an opportunity to tactfully and indirectly make a point.

I decided to invite Miller to a long talk over lunch. First I discussed his works that I’d read, my familiarity with them clearly surprised him. Then I asked what he had learned about Chinese operas and which Chinese playwrights he enjoyed. He couldn’t answer my questions. I continued to ask him whether he had heard of Tang Xianzu, a Chinese playwright from the Ming Dynasty (1368–1644). Of course, his answer was “no.” I told him that Tang had lived around the same time as William Shakespeare, and his achievements were no less grand (this is what I said at the time, though I have not actually done the research into this claim). Then I began to explain Kunqu opera. Miller began to take an interest. So I continued — introducing him to Guan Hanqing, a Chinese playwright and poet from the Yuan Dynasty (1279–1368) (a film about Guan was then the subject of a heated debate in China). I told him how Guan was active in the 13th Century, writing plays even before Dante. Miller said that he was unfamiliar with Chinese literature because he didn’t understand Chinese. I asked him whether he knew about Cao Yu, a living contemporary Chinese playwright, and his works. I told him the number of Chinese people who knew Cao was surely no less than that of Americans who knew Miller. Yet Miller knew nothing about Cao. And this time he could not use language as an excuse, because Cao’s plays, such as “Sunrise” and “The Wilderness,” had been translated into English. Still, I admitted that Chinese intellectuals had little knowledge of recent developments in the outside world as a result of the Cultural Revolution and China’s years of isolation.

|

Actors perform the Kunqu opera “The Peony Pavilion” on Sept. 19 in Suzhou, East China’s Jiangsu province. Photo: VCG |

At the end of that lunch, Miller was quite enthusiastic and sincere, telling me that we needed to strengthen our mutual communication and understanding. I didn’t accompany Miller during his visit to other places in China. But I heard from my colleagues that he had gained modesty. Now when I look back, I see how my own mind reflected the narrow views of the time. We were highly sensitive to foreigners’ attitudes and always eager to take other people down a peg, even though in China we had just emerged from a great calamity and were a long way from the liberation of thought.

An old friend and China hand

John Service (谢伟思) was an American diplomat stationed at the U.S. Embassy in China in the late 1940s; he was among the State Department diplomats who strongly opposed U.S. support for the anticommunist Kuomintang government during China’s civil war. Service also visited Yan’an (Editor’s note: Yan’an was the headquarters for Chinese Communist Party during the civil war) as a member of the Dixie Mission. He is particularly known for submitting a series of reports in his own name as a junior diplomat (at that time, second secretary) to Washington, through which he expressed his opinions and correctly predicted that China would ultimately belong to the Communist Party of China (CPC).

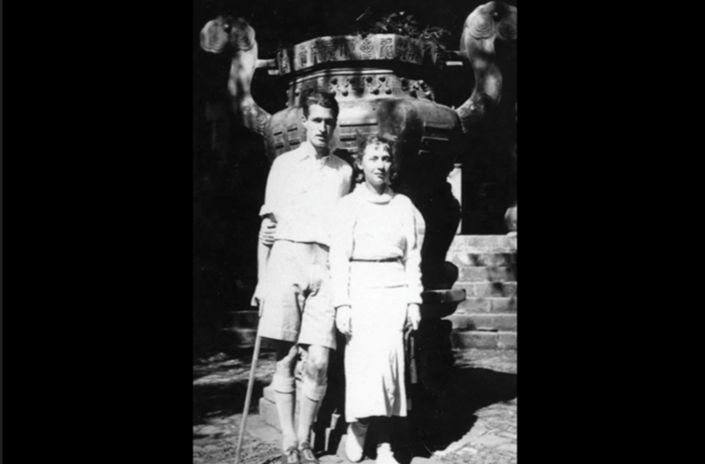

|

John Service and his wife Caroline in Kunming in 1934. Photo: Universities Service Centre for China Studies |

Before Richard Nixon paid a state visit to China as president of the United States in 1972, American scholars had already compiled Service’s reports from the declassified State Department archives into a book, which was published with the title “Lost Chance in China: The World War II Dispatches of John S. Service,” demonstrating the foresight of this young diplomat. For this reason, Service was long recognized as an “old friend of the Chinese people.” When Nixon’s visit to China was announced, the Chinese government decided to invite some international friends of the CPC to China in advance, as a way of showing that “China never forgets old friends.” Service was among them.

|

John Service’s book, “Lost Chance in China: The World War II Despatches of John S. Service.” |

Service visited China with his wife for the first time in 1971. At that time I was still attending the May Seventh Cadre School in Henan (Editor’s note: This was during the Cultural Revolution).

In 1975, during their second visit to China, I accompanied Service and his wife to Tibet, which at that time was not open to outsiders except with special approval from the Chinese government. Service was over 70 at the time and had just undergone cardiac surgery after a minor stroke. Still, he insisted he was in good enough shape. After all, if he missed this opportunity, it would only be more difficult to visit Tibet in the future. After receiving a physical examination from doctors at the Peking Union Medical College Hospital, Service was allowed to visit Tibet with his wife. I spent one week with the couple, accompanying them just in Lhasa. Unexpectedly, although both Service’s wife and I suffered from altitude sickness, he seemed completely unaffected.

Due to the Cultural Revolution, Lhasa’s temples were all closed. But visiting the Jokhang Temple and some other sites, we saw lamas chanting sutras. Upon Service’s request, several lamas were gathered to talk with him. We also visited Barkhor street, enjoying highland barley wine and butter tea in Tibetan people’s homes, and the residence of the Dalai Lama. There, what left me with the deepest impression was its fashionable and “foreign” feel. Although the decorations were in a Tibetan style, the bed, sofa, electric lamps and other household items were rather high-tech products imported from other countries. As a righteous and kind man, Service was friendly to China and praised the achievements of the People’s Republic of China. He made these comments from his own heart, measured against his own standards for freedom, equality, fairness and integrity.

In 1978, Service made his third visit to China, this time as part of an education delegation led by Clark Kerr, former president of the University of California. Although Service had helped arrange this delegation, he kept a low profile and deferred to Kerr as the group leader. 1978 marked the second year since China had resumed the “gaokao” (national college entrance examinations) and the first year of official cancellation of the “Up to the Mountains and Down to the Countryside Movement” (Editor’s note: This was massive movement that sent urban young people to the countryside to learn from the peasants). Members of the delegation had heard many criticisms of the damage done to education during the Cultural Revolution. China’s circumstances during this visit were quite different from when Service had visited several years prior. At that time, representatives of the “zhiqing” (Editor’s note: “sent-down youth” or “educated youth” of the Cultural Revolution) would talk about their experience “flourishing on the vast countryside land” and “developing their talents to the fullest through education amongst the rural population.” But by 1978, things had completely changed. Chinese officials receiving the delegation quoted speeches by Deng Xiaoping that criticized the slogan “sent-down youth should learn from the rural population” — after all, farmers were less educated than sent-down youths, so who should be learning from whom?

Service also interceded for John King Fairbank, an American historian of China and U.S.-China relations.

Fairbank was better known than Service in both the U.S. and China. As Fairbank had also opposed the United States’ unilateral support of Chiang Kai-shek and advocated for the U.S. government’s recognition of the People’s Republic of China, he had been crowded out by the U.S. government and persecuted during the McCarthy era. But in a review of Russian writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn’s “The Gulag Archipelago: An Experiment in Literary Investigation,” Fairbank compared China’s labor camps to the Soviet’s forced labor camp system, which had offended the Chinese government.

|

John King Fairbank. Photo: VCG |

Even after the detente between China and the U.S., when many Sinologists were invited to visit China again, Fairbank’s application went unapproved. This is why, on one occasion, Service took the opportunity to tell Chinese officials that Fairbank was still very friendly to China and should be allowed to visit. As for his review of “The Gulag Archipelago,” that was written during the Cultural Revolution, so it should be considered an objection to the Gang of Four (the ruling political faction within the CPC during the Cultural Revolution). This reflects Service’s honesty and kindness. As far as I know, Fairbank had a strong reputation among Sinologists in the U.S. and never paid Service any attention. Shortly after Service’s intervention, Fairbank was approved to visit China. It remains unknown whether that decision had something to do to Service’s good word.

In 1979, Wang Bingnan (Editor’s note: Wang was a former vice-minister of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs) led a goodwill mission to the United States, for which Service received members at his home in Berkeley, California. In the United States, people like Service were not only oppressed during the special period of political struggle; they were also excluded by political circles. Although Service’s diplomatic career hit a dead end (his last position was the United States consul-general in Liverpool, England), he managed to find success in other fields. After leaving the U.S. Department of State, Service entered the corporate world, working in engineering technology. He even obtained a patent for one of his inventions.

As a “China hand” whose predictions came true, Service never got his due respect, either in academia or among government think tanks, not even when Sino-U.S. tensions finally eased. China studies in the U.S. had come to be dominated by a different group.

It seemed that the older generation of foresighted Americans had been forgotten. Service told me, on multiple occasions, that when he revisited China in 1971 he had shared a courtyard with Henry Kissinger. They often met in the mornings, exchanging polite greetings; but Kissinger, despite knowing Service, never discussed China with him or consulted him on related issues. A few years later, I visited Service and his wife again at a retirement home in Oakland, California. In 1990, as usual, I received a New Year card signed by the couple. They wrote: “Dear Zhongyun, you are always in our hearts.” The simple statement conveyed a rich subtext. Two years later I stayed in the U.S. as a visiting scholar. On my way back to China, I visited Service in California again. This time, he was showing his age a bit more, no longer able to come pick me up in his car. But I didn’t expect that to be our final meeting. Later I took another opportunity to visit California, but Service had already passed away.

Shirley Du Bois

W. E. B. Du Bois was one of the earliest and most important Black American leaders of the 20th Century. He was a founder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), a longstanding and influential civil rights organization in the U.S. As an outstanding scholar, sociologist, educator and historian of African Americans, Du Bois published numerous treatises. He did not advocate violence, but his politics later shifted left, and he had a rather good relationship with the Communist Party. Late in his life, he immigrated to Ghana; one year before his death, he joined the Communist Party of the United States of America. His communist leanings are why Du Bois, unlike Martin Luther King, Jr., is not recognized in the American mainstream. I often felt this was unfair to him.

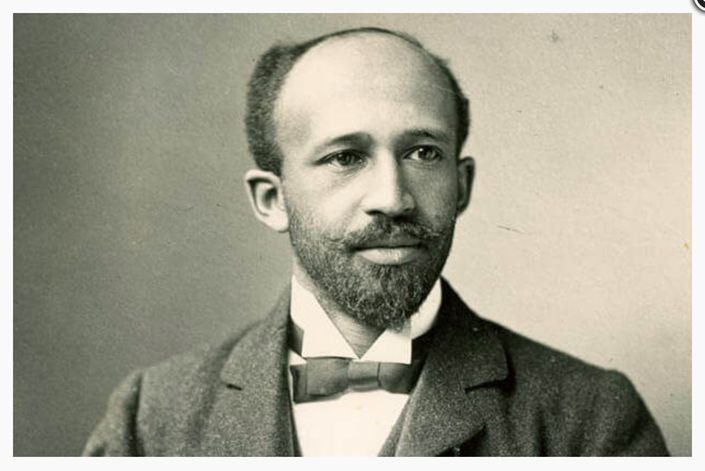

|

W. E. B. Du Bois. Photo: U.S. National Archives and Records Administration |

His wife was Shirley Du Bois, who was a social activist in her own right. In her early years, Shirley Du Bois participated in various civil rights movements and studied music and art in France. She also composed music, wrote several books and, later, even served as the Minister of Radio and Television in Ghana. After her husband passed away, Ghanaian President Kwame Nkrumah was overthrown and Du Bois moved from Ghana to Egypt. She finally returned to the U.S. in the 1970s, and taught at several universities there. However, she was frequently harassed by the Federal Bureau of Investigation for her close ties to radical left-wing organizations. In 1976, Shirley Du Bois was diagnosed with breast cancer. Fearing that American doctors would take the opportunity to kill her, she requested to receive medical treatment in China. Thus she arrived in the spring of 1976. When the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries received her, I was in charge of the formalities.

Shirley Du Bois was sent to Peking Union Medical College Hospital (PUMCH) immediately upon arrival. Since 1949, the PUMCH had been criticized and labeled as an “imperialist base of cultural aggression.” (Editor’s note: the PUMCH was founded by the Rockefeller Foundation in 1921.) During the Cultural Revolution, it was renamed the Anti-Imperial Hospital. In spite of this, the PUMCH was widely regarded as the best hospital in China, and it provided treatment for foreign guests, domestic leaders and other special individuals. Considering Shirley Du Bois’ international stature and progressive politics, along with the fact that she chose to receive medical treatment in China rather than the United States, China was determined to provide her with the best medical care they had to offer. Unfortunately, her diagnosis revealed that the cancer had spread throughout her body and was already at a terminal stage. Expecting her to only survive another three months, her doctors adopted a more conservative approach to her treatment. Upon learning about the situation, the Chinese government asked the doctors to spare no effort in extending Shirley Du Bois’ life. It was considered a “political task” because she trusted Chinese doctors rather than American doctors. This put the PUMCH’s doctors under immense pressure.

While Shirley Du Bois was staying at the PUMCH, she was visited by many leaders in the Chinese government, including Deng Yingchao (Editor’s note: Deng was the wife of Zhou Enlai), Wu Guixian (vice premier) and Liu Xiangping (minister of health). Deng mainly consoled the medical staff, commending them for working hard to save Shirley Du Bois’ life. Wu, meanwhile, told the medical staff to try their hardest, considering the international political importance of the task. I still remember Deng’s kindness to the staff.

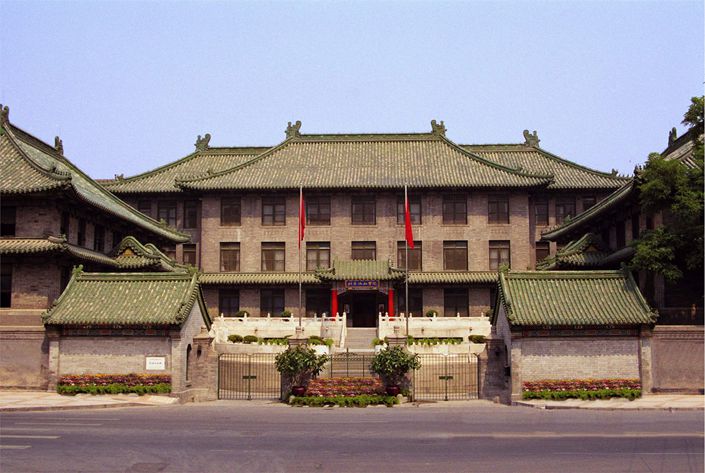

|

Peking Union Medical College Hospital in January 1951. Photo: Peking Union Medical College Hospital |

In the end, medical experts proposed a two-pronged attack: an androgen injection treatment to balance the carcinogenic estrogen, and short-interval blood and plasma transfusions. As the androgen injections caused Du Bois to grow facial hair, a hairdresser was also arranged to manage shaving. Du Bois’ temperament was also affected by the treatment, making her irritable and demanding. As for the blood transfusion, this was an extremely rare and costly therapy at that time. In those turbulent years, hospitals were short on blood. Even patients in critical condition could not get access to it. Shirley Du Bois’ medical treatment at the PUMCH continued not for three months, but for one year. In 1976, when the Tangshan earthquake occurred (Editor’s note: the magnitude 7 earthquake, whose epicenter was not far from Beijing, killed more than 242,000 people), she was transferred to the Huadong Hospital Affiliated With Fudan University for over a month (Editor’s note: Huadong Hospital is in Shanghai), after which she returned to the PUMCH. Later, Shirley Du Bois’ son, David Graham Du Bois, came to Beijing to see his mother. He sensibly declared that as his mother was suffering from an incurable disease, the hospital should not exert great efforts to prolong her life. But, as may be expected, no one proposed terminating the treatment. Finally, David Du Bois wrote a letter to the head of the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries. He expressed his appreciation for the excellent medical treatment China had provided to his mother. David Du Bois believed that medical staff had done everything in their power to save his mother, but no one could cure her of this cancer. As her son, he asked the medical staff to give up the special medical treatment for his mother, and said he would assume full responsibility on his own. With David Du Bois’ letter, everyone could breathe a sigh of relief. Shirley Du Bois passed away in March 1977, peacefully and in the company of her son.

Contact editor Michael Bellart (michaelbellart@caixin.com)

Download our app to receive breaking news alerts and read the news on the go.

Follow the Chinese markets in real time with Caixin Global’s new stock database.