Weekend Long Read: Views on China’s Green Transformation From Inside the Central Bank

Shanghai will likely be China’s first city to achieve peak carbon dioxide emissions and carbon neutrality. Why?

To start with, it has an overall urbanization rate of over 88%, significantly higher than China’s national urban average (around 63%) and even higher than that of developed countries (80%–85%). This shows how large the urbanization gap is in China. The national target for the urbanization rate is a one percentage point per year increase — it will take at least 15 years for China to approach the level of developed countries. However, we have less than nine years until 2030. Therefore, I think the 2030 carbon goal has put the country as a whole under heavy pressure. But in Shanghai the level of urbanization has surpassed the average of developed countries, even approaching the Japanese level (around 93%). So Shanghai can also be expected to take the lead in the carbon peak and neutrality initiatives.

Still, we need to keep in mind that urbanization is an evolving process. The current urbanization rate only takes the local population structure into account. Besides current residents, we must also consider the factor of migration. As Shanghai continues developing, migrants are likely to keep pouring in. This will fuel large-scale investment and never-ending demand for infrastructure and public services, which in turn will require more steel, cement and concrete as well as crude oil, power and natural gas — all of which are carbon-intensive and leave a big environmental footprint.

Therefore, Shanghai has the conditions to succeed, but it won’t be an easy task. But we should identify specific quantitative objectives and approaches to achieve peak carbon dioxide emissions which can then serve as a foundation for carrying out other work.

|

Finance-led evaluations

Financial institutions will need to carefully check and evaluate their own balance sheets. As long as the two carbon goals are national requirements supported by the central government and quantifiable constraint indexes, their strict implementation may impact financial institutions’ business and balance sheets quite significantly.

Some financial institutions may be very good at traditional risk management and controlling regulation indexes, such as the non-performing loan ratio (NPL ratio), capital adequacy ratio and the liquidity or concentration ratio indexes. However, further investigation reveals that about 70% to 80% of assets on their balance sheets are carbon-intensive or have a high environmental impact. This suggests these financial institutions may be vulnerable to risk in the next step of transformation and systematic asset revaluation.

Green finance: Meeting the international standard

At a macro level, there are generally three major areas in the green and low-carbon transformation that are supported by finance — green finance, the carbon market and transformative finance.

Ever since seven ministries and commissions, including the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), jointly issued the “Guidelines for Establishing the Green Financial System” in 2016, the whole financial community has gradually reached a consensus on the development of green finance and begun taking practical steps in reform and innovation. After five years of development, China’s green finance has ascended to the world’s top echelon with its credit balance ranking first and green bond issuance ranking second.

Nevertheless, we should remember that green finance is strictly defined and follows a rigid classification scheme. At the international level there is a wide consensus on an increasingly mature definition and set of standards for green finance. This rigidness in definition, classification and standards means that financial products and services have to meet certain qualifications.

The PBOC, National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) and China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) recently issued the latest edition of the “Catalogue of Green Bond Projects Under Support (2021).” The new edition includes two remarkable advancements: first is the fact that the catalogue was jointly issued by the three ministries and commissions, unifying a set of consistent standards; second and more importantly, the catalogue is geared toward international standards, disqualifying what were once considered “green” clean coal utilization projects in China but did not meet standards for international recognition. In other words, not all financial products and services that support green transformation automatically qualify for the label of “green finance.” In fact, a key task of green finance regulation is the prevention of “greenwashing.”

What does this mean? It’s a reminder of limitations on the scope and coverage of green finance, a reminder that we cannot pin all our hopes on green finance.

Statistics indicate that China’s green credit balance is approximately 12 trillion yuan ($1.9 trillion) and its green bond issuance now exceeds 900 billion yuan, approaching 13 trillion yuan in total. But this is still not enough for China to realize green transformation, its emissions peak and carbon neutrality. These goals will require a level of investment and financing at approximately 100 trillion yuan. PBOC President Yi Gang has taken many opportunities recently to elaborate on this point.

Recently, Goldman Sachs released a report entitled “China’s Path to Net Zero” which estimates that China reaching its carbon neutrality goal will require an investment of $16 trillion. Compared with 100 trillion yuan of investment and financing needed for the green and low-carbon transformation, the current financial scale of 13 trillion yuan may not be nearly enough. In addition, after years of support and promotion to bring green finance to the large scale it is at today, its future development will be challenged by diminishing marginal returns. As quality projects become scarce, the cost and difficulty of further development may increase. In anticipation, we need to broaden our horizons now, pulling attention and energy to the development of transformative finance even as we continue to vigorously develop green finance.

Transformative finance: A practical solution

Unlike green finance, transformative finance is more flexible, adaptive and targeted. The international community has already reached a preliminary consensus on transformative finance, but unlike green finance, there is no strict definition, no clear set of standards and no catalogue of classifications.

Specifically, the preliminary international consensus is on the broad definition of transformative finance as financial support given to a certain investment, economic activity or business behavior that has clear targets for low-carbon transformation and net zero carbon emissions, specific implementation paths, technical plans, clear and performable assessment indicators, a system of evaluation and the willingness to adhere to strict information disclosure and accept social supervision, even if the activity in question is carbon-intensive or has a large environmental footprint.

Transformative finance is thus more flexible, adaptive, targeted and practical, with wider coverage than green finance. Especially for industrial countries like China, which has such a massive scale of high-emissions industries, I believe transformative finance to be of great significance.

Although there is this consensus on a broad definition, there are no specific classifications or standards for transformative finance at present. Formal international discussions on this issue only began in March of last year. Almost all of the documents regarding transformative finance — issued variously by a small number of polities or international organizations, such as the European Union, Japan, the Climate Bonds Initiative and the International Capital Market Association — are tentative, still in their infancy. Undoubtedly, this is a great opportunity for China. We can and should seize this chance to actively participate in discussions, research and experiments, striving to be a player, contributor and leader in the development, innovation and standardization of international transformative finance.

Moreover, the international community has recognized that different countries will take different paths to achieve low-carbon transformation and net-zero emissions in accordance with their economic and social conditions, stages of development and industrial compositions — this is another international consensus worthy of our attention. Even if countries across the world have reached a consensus on green finance, with increasingly convergent and relatively strict corresponding standards and classifications, it is unlikely that classifications and standards will be unified among all the specific areas of support. Instead, most cases will follow the principle of “seeking points of commonality while reserving difference,” a better reflection and full respect of various countries’ differences in transformation path.

Just so, when it comes to implementing the low-carbon transformation and working toward the two carbon goals, the case of Shanghai will be quite different from that of Jiangsu, Guangdong, Hubei or even Beijing. Thus it is necessary to explore, as soon as possible, the most appropriate transformation path and corresponding financial support plan considering Shanghai’s socioeconomic development and industrial composition, especially if Shanghai is to take the lead in achieving peak carbon dioxide emissions and carbon neutrality.

Carbon market

As for the carbon market, I have long been advocating for the construction of a market for carbon that conforms to the rules of the financial market. I have also called for advancing the market’s design, development and innovation using financial concepts, methods, tools, products, services, infrastructure and even the financial supervision and management framework. Carbon market commodities — or more precisely, the carbon emission rights themselves — are more or less standardized financial products. They have distinct financial features; they can be divided, standardized, registered for trusteeship and participate in continuous trading.

Internationally, as in the more mature European carbon market, spot transactions usually account for less than 20% of the total; more than 80% of emission rights trading is in futures. Although it is clear that our carbon market will be operational in June, there are still a number of critical issues that I believe require further discussion and clarification given the current positioning of its design.

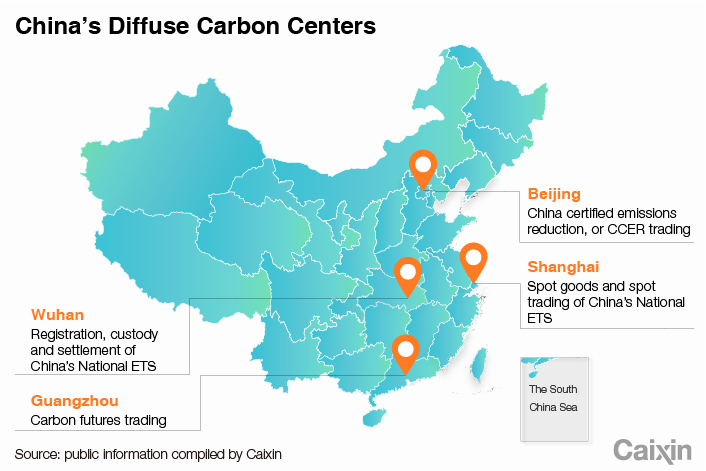

First, the diversity of its market players is severely lacking. Its main body includes 2,225 power enterprises, but lacks participation from various other sectors, including finance. Second, the market is only designed for spot trading, with futures and other derivatives trading not under consideration for the time being. Third, in terms of market infrastructure design and institutional arrangements, Shanghai is the designated location for spot goods and spot trading; Wuhan is the location for registration, custody and settlement; Guangzhou is for futures trading, and Beijing is for CCER trading. I’m worried that this regional fragmentation of markets and infrastructure will result in low efficiency, making it difficult to achieve a large volume of trade and hindering the formation of quality mechanisms for pricing and discovery.

|

Fourth, there are many other basic issues which have yet to be clearly interpreted — for example, quota determination, the legal attributes of carbon quotas’ property rights, accounting measurement, financial processing and risk measurement. This makes me worry if the market really will be ready to enter successful operations in June as scheduled.

In spite of these concerns, Shanghai possesses favorable foundations, conditions and talents for the launch of the national carbon market.

Shanghai’s carbon market is the current leader among the seven carbon markets nationwide. This means the municipality must take on corresponding responsibilities — regarding the carbon market as a financial market, clarifying its financial features, arranging the supporting infrastructure and basic systems and promoting the design, construction and development of the carbon market in accordance with the laws of the financial market.

International cooperation

Shanghai should strive to be at the forefront of international cooperation on carbon. The holdings, transactions and supporting services of relevant financial assets — whether they are carbon assets, green finance assets or transformative finance assets — must be considered from a global rather than a solely domestic perspective.

China is currently in the lead in terms of its post-pandemic economic recovery. This is a great advantage, enabling China to maintain a stable and healthy macroeconomic situation and provide yuan assets with good security and a high rate of return. If China allows global market entities to enter its market, share the benefits of its fast-growing economy and obtain the high returns of yuan assets — especially if China offers them yuan assets involved in the green transition, ESG and sustainable development — this will only further assist China’s financial opening-up, implementation of the new development pattern of “dual circulation” and execution of the requirements for high-quality development. Meanwhile, China will be able to play its role as a great power, shouldering responsibilities, taking on missions and building a community with a shared future for mankind. Of course, it will also be conducive to the internationalization of the yuan and construction of the Shanghai International Finance Center.

As for China’s Belt and Road investment projects or sovereign bonds issued overseas, if a portion of them have a good rate of return, have generated cash flow or (if possible) are green bonds, we should be willing to securitize them for investment in the global issuance of green bonds or similar products. For one, this will allow us to strip these assets from the balance sheet as early as possible and gain early returns, recover cash flow and better disperse and control risks; for another, this will allow investors from all over the world to purchase these assets and share in the high returns and cash flow of the Belt and Road investments.

In China, there are currently nine cities in six regions piloting green finance reform and innovation projects. They’re achieving remarkable results. Shanghai can consider leveraging its current advantages to bring itself into the scope of pilot zones for green finance reform and innovation. It can then implement comprehensive reform and innovation in products, services, technology, relevant infrastructure and systems, giving the financial industry the chance to support the municipality’s pioneering work on green transformation, peak carbon dioxide emissions and carbon neutrality.

Zhou Chengjun is the director of the People’s Bank of China financial research institute. It is based on a speech Zhou delivered on May 13 at a symposium called Improve the Green Finance Policy System, Facilitate the Building of Shanghai Financial Center at the Shanghai Institution for Finance and Development.

Translated by Lan-bridge Communications.

Contact editor Joshua Dummer (joshuadummer@caixin.com)

Download our app to receive breaking news alerts and read the news on the go.

Get our weekly free Must-Read newsletter.

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR