How the ‘Tree’ of Chinese Writing United People Through the Millennia

(ThinkChina) — From the oracle bone scripts of the past to the Modern Standard Chinese script of the present, written Chinese is pictorial and highly evocative. What’s more, it has a unifying effect on Chinese culture. While Chinese languages vary from place to place, the written script remains similar. Singapore’s Teo Han Wue explores the characteristics and philosophy of the Chinese writing system.

(Photos provided by Teo Han Wue unless otherwise stated)

As a teacher of Mandarin at an international school decades ago, I was puzzled as to why many of my ethnic Chinese students hated the subject while other students and colleagues welcomed the opportunity to learn it.

Though I couldn’t accept that these kids should be so indifferent if not hostile to their own heritage, I somehow came to rationalise that they had no motivation to learn what was widely regarded as the world’s hardest language. After all, schooled in an Anglophone education system, they most probably felt English was all they would ever need.

Besides, they could not have foreseen China’s rise that is only too obvious today. Neither did they, being children of expatriate families, see any real functional purpose of it given the social circles they moved in.

That was the early 1970s and the tide has definitely turned since. In many parts of the world there is growing demand from students learning Chinese. Perhaps those erstwhile detractors, now grown up, would need little persuasion to ensure their own children do well in Mandarin instead of rejecting it as they themselves did.

Singapore’s fading bilingual advantage

However, during a half-century that saw increasingly keen interest in studying Chinese worldwide, Singapore seems to have been still struggling with doubts about its own bilingual advantage. There has also been concern and anxiety about the declining standards of Chinese among younger Singaporeans.

|

Singapore's founding Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew made repeated pleas to Chinese parents to speak Mandarin to help lighten the learning load of their children. In this photograph, he is making his speech at the opening of the Speak Mandarin Campaign at the Singapore Conference Hall on Sept. 7, 1979. Photo: SPH |

For a start, the term “mother tongue” for Mandarin has frequently been disputed by many ethnic Chinese especially the English-educated, who are identifying increasingly with English and the Chinese languages of their parents and grandparents. There has also been growing concern about the decline of Hokkien (Fujian or Minnan), Cantonese, Teochew (Chaozhou), Hakka and Hainanese due to the annual Speak Mandarin Campaign.

|

Speak Mandarin Campaign posters in 1979, when the campaign was first launched. Photo: SPH |

On the 40th anniversary of the annual Speak Mandarin Campaign in 2019, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong cautioned that Singapore may be losing its bilingual competitive edge; he quoted a Ministry of Education report to illustrate how English had become the main language in most Chinese households.

Why might Singapore be losing the advantage which should have been one of our greatest strengths despite so many decades of bilingual policy reinforced with a national drive to speak Mandarin?

Written Chinese overlooked

Could it be that we have been too preoccupied with how Chinese variants are spoken rather than how they are written? In 1999, The Straits Times ran an extensive feature arguing vehemently that Mandarin was not the mother tongue of Chinese Singaporeans and had been erroneously categorised in schools as such. A Harvard scholar Lee Ou-Fan happened to be in town and was asked to comment. He stressed that one could not discuss the Chinese language without considering its writing. Nonetheless, the newspaper stuck to its guns still insisting on separating spoken Chinese from its written form, which led to Lee reiterating his position in a newspaper column in Hong Kong.

Indeed a proper understanding of the Chinese language must begin with an appreciation of the exceedingly important position of its writing system, which seems to have often been overlooked, especially in Singapore.

|

Seal carving “一日复一日” (Day after Day) by Nyan Soe. |

Once, gazing at some Han dynasty inscriptions on bamboo strips in a museum I visited in China some years ago, I was amazed by how parts of the ancient text still spoke to me, a Singaporean, more than 2,000 years later because I could read some of the characters which were strikingly similar to their modern written forms.

When watching the Beijing Olympics on TV in 2008, I noticed how the pictograms for various events were symbols inspired by hieroglyphic scripts on ancient oracle bones of the Shang dynasty (about 2000 B.C.) and bronzes of Zhou (about 1000 B.C.) presented in the seal-carving style, signifying a lineage going back to its distant past.

|

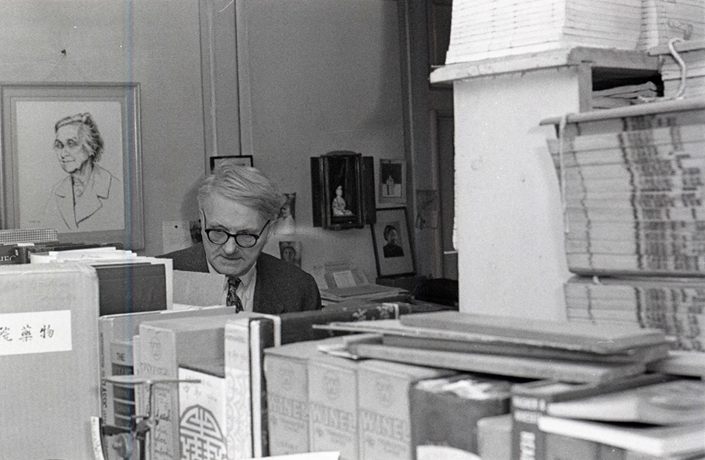

British biochemist turned sinologist Joseph Needham (1900-1995), who started learning Chinese at 37 before starting his monumental work “Science and Civilisation in China,” refers to written Chinese as a powerful factor in assuring the unity of Chinese culture in the face of geographical division.

In his view, whether a Chinese poem was written 1,000 years ago or yesterday, it is as readable and enjoyable to one who has mastered the language. The literature of the millennia is open to the Chinese.

|

Joseph Needham in his office in 1965. (Photo: Kognos/Licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0) |

“It is true that this old language, in spite of its ambiguity, has a concentrated laconic, lapidary quality, making an impression of austere elegance, pith and virility, unequalled in any other invented instrument of human communication,” Needham writes in the introduction to his work mentioned above.

A constant through the ages

This idea of Chinese cultural unity through the written language is even more fully articulated by Jao Tsung-I (1917-2018), a great classical scholar known also for his work on epigraphy and ancient languages such as Sanskrit and Akkadian, an old Semitic language now extinct. Written Chinese evolved from the oracle bone script about 3,700 years ago, always based on a one-character-one-sound (monosyllabic) principle. While pronunciations differed due to geographical divisions, written Chinese developed separately after it was standardised under Qin Shi Huang (259 -210 B.C.).

This process has led to the entire ethnic Chinese population using the same script wherever they are and however they speak. Unlike Latin in Europe, says Jao, where it changed according to the language as spoken in different regions over time.

|

Jao calls written Chinese “a great miracle” and likens it to a huge tree blending calligraphy and drawing, with its literary expression in visual and aural forms developing into a highly aesthetic entity.

This miracle has fascinated people since ancient times and has today continued to inspire artists not only in China but also around the world.

In his iconic 1988 work “Book from the Sky,” which is a text printed with completely unrecognisable and meaningless characters, celebrated Chinese artist Xu Bing deals with the identity of Chinese. Twenty years later he turned to the flip side of the same language issue in “Book from the Ground,” which tells a story in the most widely used symbols and emoticons that anyone anywhere can understand.

|

Cover of Xu Bing’s “Book from the Ground.” |

Xu Bing names French thinker Jean Douet who suggested in 1627 that Chinese was a potential model for an international language and credited it as the inspiration for creating a book with only symbols instead of writing. Today human communication seems to be happening more often with images as predicted by the philosopher centuries ago.

|

From Xu Bing’s “Book from the Ground” is told entirely in symbols and emoticons instead of written words. |

“Traditional methods of learning and accessing information is increasingly being replaced with recognition of images. Mankind seems to be replicating the history of character-forming starting with the mode of the hieroglyphics or pictographs yet all over again,” says Xu.

Sealed with passion

For some time I have been observing a group of young Singaporean seal carvers practising the art of engraving characters on hard surfaces such as stones and ceramics. The work they did early last year fascinated me with what they have made possible with this very ancient art form otherwise regarded as antiquated or archaic.

|

Young seal carvers learning the art of engraving characters on hard surfaces. |

Instead of the usual literary references suggesting poetic elegance, they carved phrases that expressed their edgy responses and reactions to the pandemic. It was as though their feelings of fears, anxieties and hopes facing the threat of Covid-19 had found expression or relief as they worked in solitude with intense concentration struggling with the strict constraints of this very old traditional medium.

When I discussed with seal carving instructor and artist Oh Chai Hoo this series of seal mark prints his students made, he readily mentioned Jao Tsung-I’s analogy of the “tree of Chinese writing” saying, “Yes, the beautiful tree grows here too and the unique aesthetics of the characters is its greatest appeal.”

|

Artist Oh Chai Hoo working on a seal carving. |

Those who still debate about the mother tongue of ethnic Chinese without reference to its written form should consider this tree that Jao calls a great miracle.

This story was first published by ThinkChina.

Download our app to receive breaking news alerts and read the news on the go.

Get our weekly free Must-Read newsletter.

- MOST POPULAR