Weekend Long Read: A Groundbreaking Architect’s Journey From France to China

If you’re a parent in Beijing, you’ve most likely been to Beijing Children’s Hospital at least once. At present, it is China’s largest and best children’s hospital. However, what few people know is that Léon Hoa, a legendary Chinese architect who divided his life between China and France, was chief designer of the hospital in 1954.

Hoa (华揽洪) drew up plans that were in line with functions and procedures of modern hospitals, including how people moved through the building. His designs featured a number of special spaces that took children and their parents into in consideration. The hospital’s exterior has a modernist, minimalist facade. Its flat rooftop tilts slightly in a nod to traditional Chinese architecture.

In 1957, the Chinese architect and architectural historian Liang Sicheng (梁思成) judged the building this way: “I think the best new building in China over the past several years is Beijing Children’s Hospital. That’s because its architect Léon Hoa understands the basic principles of Chinese architecture, designing the hospital’s room and window widths to the proper proportions for demonstrating our national style.”

|

A photo sent by Zhu Futang from Beijing Children’s Hospital to Léon Hoa in 1955. |

In the architectural circles of 1950s China, “large roofs” were the dominant trend and the norm was “socialist content plus national form.” Hoa had his own opinion on this point: “If we’re just imitating by collecting decorative patterns, we end up sacrificing comfort and economic advantages for outdated forms, and there is nothing resembling progress.”

Beijing Children’s Hospital offers powerful proof of Hoa’s claim. The hospital succeeds in combing socialist content with national form, but without following mainstream architectural design. Unlike architects seeking fame for their national styles, Hoa was more interested in providing convenience to ordinary people: How, under the given constraints, can one create the best conditions for their well-being?

This hospital officially opened on June 1, 1955. Decades later, Chinese architects widely regard it as one of the most successful works of architecture since the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949. It has also been recognized internationally, included in “Sir Banister Fletcher’s A History of Architecture (20th edition)” in 1996. Its place in the history of world architecture is secure as a representative of outstanding work of 1950s Chinese design.

A star in France

In 1912, Léon Hoa was born in Beijing’s “hutong” alleyways. His father, Hoa Nankouei (华南圭), was a well-known railway and municipal engineer who also taught architectural engineering. The elder Hoa was also one of the first government-sponsored Chinese students sent to France to study in the early 20th century. Hoa’s mother was a Polish author who wrote in French. Hoa Nankouei personally designed their hutong home, which featured a combination of Chinese and Western styles. The younger Hoa thus grew up immersed in Chinese and French cultures.

At 16, Hoa’s parents sent him to Paris to complete high school. He was later admitted to his father’s alma mater, ESTP Paris. In 1936, he was granted admission to the Beaux-Arts de Paris; six years later he obtained a an advanced degree in architecture. The year of his graduation, he married a French woman named Irène. The tranquility of Hoa’s life was soon broken by the outbreak of World War II. During the war, Hoa participated in the French Resistance and joined the French Communist Party. As the war progressed, Hoa and his family were forced to move south to Marseille. In spite of the surrounding social upheaval, he managed to start a career in architectural design.

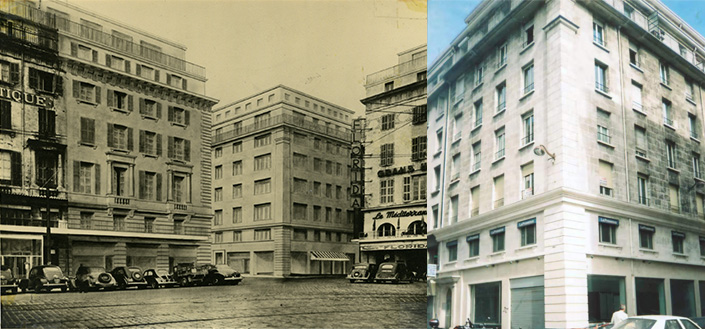

|

A veterinarian that located in the suburban area of Paris, designed by Hoa in 1937. Photo: Courtesy of Hua Xinmin |

For the first few years, he worked in the architecture office of his mentor, Eugene Beaudouin. After the war ended in 1945, Hoa established his own firm. The vast extent of post-war reconstruction in Europe gave him the chance to engage in dozens of urban planning and architectural projects, ranging in scale from huge urban areas to small private villas. Hoa was the only Chinese architect practicing in France at that time. Completing numerous projects before he was 40, Hoa became a star in the French architectural world.

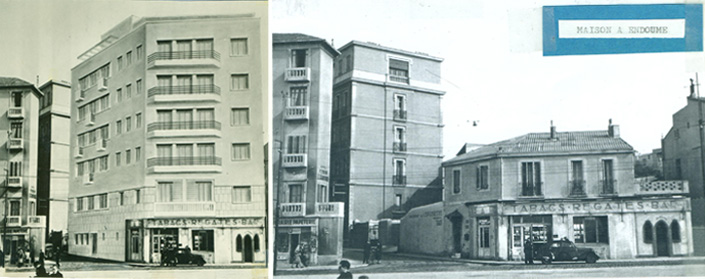

|

An apartment located in Marseille, France designed by Hoa in 1948. Photo: Courtesy of Hua Xinmin |

|

An apartment designed by Hoa in 1950 in Marseille. Photo: Courtesy of Hua Xinmin |

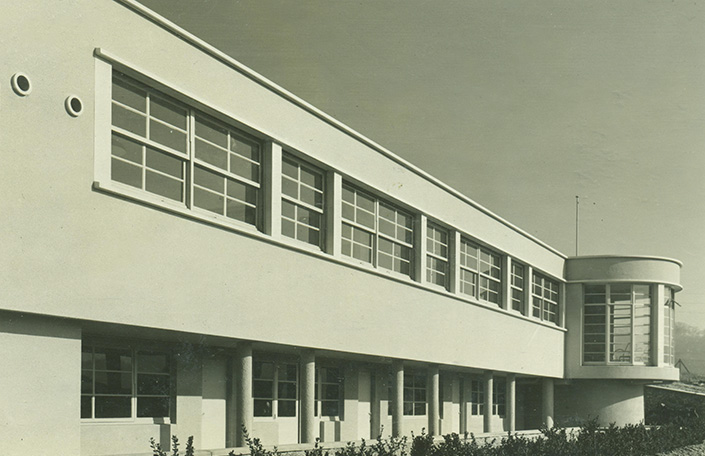

|

A student canteen designed by Hoa in Marseille in 1951. Photo: Courtesy of Hua Xinmin |

‘China awaits your return’

However, Hoa’s attention was soon drawn to the rapidly changing China emerging out of revolution and war. He learned that his father was then serving in the Beijing Municipal Commission of Urban Planning. This helped convince him that China — his faraway childhood home — was ushering in a promising, if unpredictable, new future.

During a chance encounter, Hoa met a member of the Communist Party of China in France and expressed his wish to return to the country. Three weeks later, as Irène was returning home from the farmer’s market, the family received a telegram from the Chinese government. It was written in English: “China awaits your return. Provided for your travel is $2,000, available at the bank.”

All long-awaited dreams can be overwhelming when they finally come true. Should they really just up and go, leaving behind their lives in France?

Hoa made the call: “Let’s go there first, and consider the future later.”

He proposed that the family live in China for five years. If everyone found they could get used to life there, then they’d settle in.

Which post-war country would be more suitable stage for Hoa’s talents — France or China? This question never seemed to loom large in Hoa’s mind. Instead, his only concern was that China — a country of longstanding poverty and weakness — had great need of him. Continuing to build things in France would have been easy, but alleviating the suffering of the Chinese people through urban construction would be more of a challenge — clearly more valuable.

A shelved blueprint for Beijing

Hoa’s father did not support the decision. The father had a certain intuition, honed through the experience of countless social upheavals in 20th century China, which told him his son would suffer from this impulsive move.

Beijing presented a major challenge for urban design.

At the People’s Representative Conference of Beiping (Beijing’s previous name) in 1949, Hoa’s father proposed a plan to build a new urban area in the capital’s western outskirts. Then in 1950, Liang Sicheng and Chen Chan-siang (陈占祥) put forward their well-known “Liang-Chen Proposal,” which also supported building a new functional city in the outskirts while keeping the old city intact. After numerous discussions and a variety of drafts, the younger Hoa and Chen Chan-siang were assigned the task of preparing two overall schemes in March 1953 for Beijing’s urban plan, tabbed as Plan A and Plan B. However, the government ultimately selected a third plan, which was influenced by the Soviet style.

|

Hua (left) and Chen Chan-siang (right) in Beijing in 1954. |

An academic intuition informed the Hoa and Chen that there must be some problems with this rigid and dogmatic scheme. However, considering the urgency of China’s need to develop industry under the planned economy, as well as the Soviet experts’ overwhelming influence on the decision-making process, their suggestions went unheeded.

The village of happiness

Hoa turned to different type of design — residential. In 1956, he began working on design for the Happiness Village (Xingfucun) neighborhood, a project that further demonstrated both his modernist design and humanist compassion.

“In early 1956, I received some opportunities to design large projects, but I wasn’t interested in those, and I didn’t want to follow the mainstream trend of historic-nostalgic architecture, either. Instead, I found the concept of planning of a ‘community’ — a more complete residential area centered around a primary school, with kindergartens, shops, clinics and other service institutions — a subject worthy of study.” Léon Hoa used this highly commonplace assignment to explore a new concept of design that could not only resolve urgent needs but also provide a quality environment to live in.

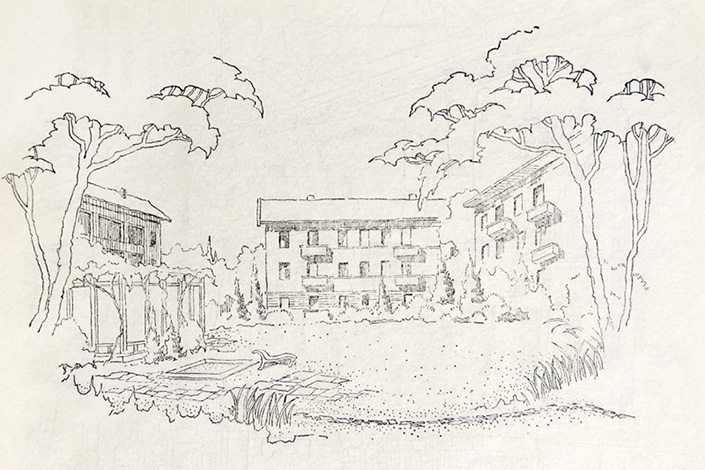

|

A sketch of the Village of Happiness made by Hoa. |

|

The appearance of the Village of Happiness in the 1950s. Photo: Hong Kaiyuan |

Hoa’s design took full account of essential human needs — including the layout of residences, the orientation and lighting of the buildings, as well as recreation areas and basketball courts to complete public facilities for business and education. It was a paragon of community design.

Those details sound all too familiar today, but in the 1950s, when people had little experience living in such communities, they were unimaginable. Hoa was so ahead of his time that he even considered transforming a grassy area into 80 to 100 parking spaces for future residents, even though it would be more than four decades before private cars lined China’s streets.

Who says there is no decency and dignity in a simple life? Who says a life with few resources has to be an unhappy one? The modern concepts Hoa applied to Happiness Village’s design were neither standardized construction industry processes, nor mechanical functionalism, let alone a particular style in architectural form. For him, “modernity” was about people — specifically, about meticulous care for the occupants of a building.

Engulfed in upheaval

Hoa had a voice in architectural circles. From 1956 to 1957, he published several articles whose content made him the object of “pidou”

sessions, or struggle sessions. The elegant architect was repeatedly subjected to all manner of accusations and abuse. He was forced to write a 7,000-word self-criticism entitled “Admittance of Guilt.”

The following year, Hoa was sent first to a hotel formwork depot in the Muxidi area of Beijing. He was tasked with moving and dismantling formwork, transporting formwork by pulling trolleys and pulling out nails and hammering them straight for reuse. Except on weekends, he lived with the other workers in a shed that contained about 20 berths.

In 1959, on the eve of the 10th anniversary of the founding of the PRC, a newspaper reported that representatives of the French Communist Party (PCF) had come to China to attend the National Day celebration. Hoa sighed: “I myself was a member of the PCF, and acquainted with them, but how can I meet them now as I’ve been labeled an anticommunist?”

Under the heavy weight of reality, there were strange moments where Hoa felt as if he were in living in a dream where he still felt a sense of normalcy and had a measure of dignity. Moments melted into each other. Feelings too.

Once, after one of his public struggle sessions where members of the audience took turns criticizing him, Hoa went to Beihai Park to meet his wife. While crossing a bridge, they encountered Feng Peizhi, director of his superior planning bureau. Feng politely grasped the couple’s hands in a warm handshake. At this moment, Hoa noticed a bright light and group of people rushing about busily in the distance. He recognized his eldest daughter among them, wearing a red scarf. Just by chance, his daughter had also come to Beihai Park for a rehearsal of the film “Kite,” a children’s feature produced together by China and France to reflect their people’s mutual friendship.

Although Hoa and Chen Zhanxiang were vindicated in the 1960s and their reputations cleared from false accusations, Hoa could not get a proper job for the next 10 years.

Singing “La Marseillaise”

Despite the gloom hanging over his household, Hoa remained an outstanding figure, not only for his distinctive appearance, but for his persistence. Even in such manic times, he didn’t lose himself or his sense of morality.

While doing hard labor, he would lead the workers in singing the French national anthem “La Marseillaise” — once in French and once in Chinese, though most of the workers weren’t sure what they were singing. And each day, the first thing he did when he went into the office was to call his wife Irène and say that everything was OK. At lunchtime, he would call her again, and never allowed any struggle sessions to break this part of his routine.

When Hoa had nothing to do, he would look for something to improve himself. Thus he began compiling the “French-Chinese Glossary of Architectural Engineering.” He gained a detailed understanding of the distribution of trees in Beijing, knowledge that would later help him protect these trees and incorporate them into the overall protection of the ancient capital. He compiled the information and sent it to the mayor of Beijing at the time. An overpass in western Beijing was the first urban overpass to be built in the city. Hoa identified a number of problems with its design. After that, he developed research programs for more than 10 overpasses. His contributed research went through many hands, from architects to municipal designers to the municipal government, but was ultimately applied in the construction of the Jianguomen overpass. Hoa’s name, however, did not appear on the list of designers.

Return to France

In 1977, Hoa was 65 years old. Irène had retired from her job at the Foreign Languages Press, and the whole family wished to return to France.

Twenty-five years had passed since the day they had hastily set off for China. After returning to France, Hoa traveled the country from north to south, visiting old friends along the way. Good memories of car trips and the jazz music he used to love came back to him, reminding him of his happy life as a youth, relaxing at gatherings with friends. It all seemed like a lifetime ago. Hoa’s modern design concepts had never really been understood or accepted in China, but in the West, where postmodernism had swept in, modernism was already outdated, becoming an object of question and critique.

More importantly, it seemed, Hoa was simply destined to be a lonely narrator.

No one around him could really understand the historical significance of the specific Chinese experience, let alone empathize with Hoa’s personal trials of physical and mental suffering in China. The weight of those 25 years was not lessened by the passage of time or the change of surroundings — on the contrary, those memories became even more difficult to bear with the distance from his homeland.

|

Hoa poses for a photo in front of a court that built in the 15th century in Rouen, France in 2010. |

In 2002, at 90 years old, Hoa was awarded the Commandeur dans L’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (Highest Order of Arts and Letters) by the French Minister of Culture for his lifelong contribution in the field of Chinese-French architecture and cultural exchange: “Throughout your career, you have shown an extraordinary sense of professional responsibility and integrity.”

In 2006, the Chinese version of Hoa’s “Reconstruire la Chine” (“Reconstruct China”) — published in France in 1981 — was finally released. But his wife also died that year.

Hoa took his last long journey at the age of 98. Immediately upon arrival at the Old Port of Marseille, he recognized an apartment he had designed in the post-war reconstruction period. And when he had left France, he had left behind drawings for a middle school; by the time he returned, it had housed generations of teachers and students. In the nearby city of Arles, a milky modern-style apartment he had designed still stood, 60 years later. At 3 a.m. on Dec. 12, 2012, the centenarian slipped away quietly in his sleep.

The last dessert he had eaten was a hawthorn cake brought from Beijing. Opposite his bed hung a print of one of Xu Beihong’s famous horse paintings. It had been purchased from the old antique street shop in Beijing. At the end of his life, he gazed upon it every day.

Contact editor Michael Bellart (michaelbellart@caixin.com)

Download our app to receive breaking news alerts and read the news on the go.

Get our weekly free Must-Read newsletter.

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR