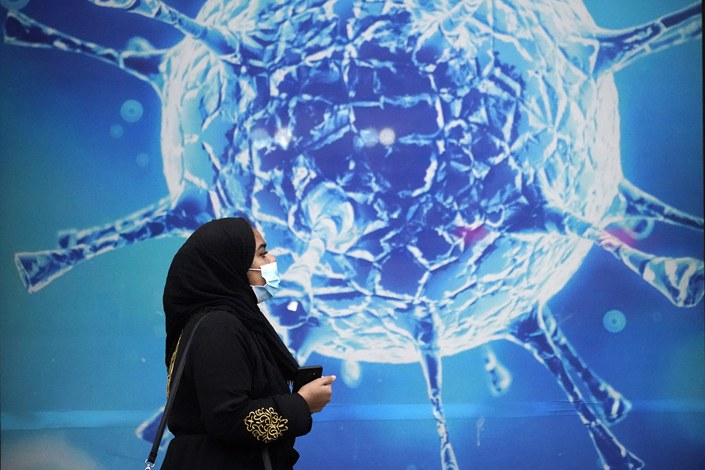

Blog: Repurposed Cancer Drug Shows Potential for Treating Covid-19

Listen to the full version

On May 13, the state-owned Science and Technology Daily published an article entitled “Chinese Scientist Discovers a New Drug for the Treatment of SARS-CoV-2 Virus and Obtained Invention Patent Authorization,” which excited readers in the science community and the general public.

According to this report, the applicants are professor Tong Yigang, dean of the School of Life Science and Technology at Beijing University of Chemical Technology, and his team. In Tong’s 2020 paper, he used in vitro cell models to screen 2,406 drugs that have been approved for treating other diseases in an effort to find components that can inhibit virus activity, with the goal of discovering drug candidates that can be used to treat Covid-19. This strategy is called “drug repurposing,” which in layman's terms means “repurposing an old drug.”

Unlock exclusive discounts with a Caixin group subscription — ideal for teams and organizations.

Subscribe to both Caixin Global and The Wall Street Journal — for the price of one.

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR