Is China Succeeding in Its Efforts to Curb Smog?

(Beijing) — Desperate times call for desperate measures. Or so said one family that decided to leave smog-choked Beijing for a leafy border town near the Mekong River.

Huang Jingjing and many of her neighbors in a newly built apartment block in Xishuangbanna — more than a nine-hour drive from China’s “spring city,” Kunming — call themselves “smog refugees.” Huang said she decided to quit her well-paying job as a civil servant in the Chinese capital after her 4-year-old daughter developed a chronic cough and signs of asthma.

“Half the students in my daughter’s kindergarten (preschool) had coughing spells or a fever that lasted for several days around New Year,” she said.

Smog blanketed Beijing and many cities in northern China for nine consecutive days from Dec. 30 to Jan. 7. Kunming, the provincial capital of Yunnan, is one of the top 10 cities in terms of the cleanest air in China. Xishuangbanna is not one of the cities whose air quality the Ministry of Environmental Protection is monitoring.

Many of Huang’s neighbors are also those who have fled the filthy air in northeast China’s “Jing-Jin-Ji” — shorthand for Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei. (“Ji” is a one-character abbreviation often used for Hebei province.)

Policymakers have proposed integrating these three areas into an immense megalopolis to rival any other in the world. Despite coordinated efforts to tackle pollution and congestion in this region, families like the Huangs are leaving because they say years of government efforts have done little to improve air quality, particularly in winter.

|

|

Hundreds of flights were grounded by smog at Beijing Capital International Airport on Dec. 25, 2015. Photo: Visual China |

Northern China was choked by two serious spells of smog in the winter of 2016-17, triggering the highest government warning for foul air, in dozens of cities, where schools were shut, highways closed and flights canceled due to poor visibility. One-fifth of the country was engulfed by toxic air for a week in mid-December, and just two weeks later, 60 northern cities, including Beijing, rang in New Year’s amid a red alert when the foul air lasted for nine days. Huang left the capital just weeks after purchasing her apartment in Yunnan in late December.

A short time-lapse video, shot by a one-time Beijing resident, showing a mass of brown-colored air on Jan. 02, 2017 assaulting Beijing, went viral.

There aren’t any official figures in China about people relocating due to pollution, and therefore it is difficult to say whether the Huangs’ case is part of a larger trend. But 41% of those living in the country’s smog-stricken north said they frequently thought about leaving for a place with cleaner air, a recent China Youth Daily survey found. Another 14% have already left.

“Many of my neighbors still head back to Beijing and Hebei to work for most of the year while they leave their elderly parents and children behind in Xishaungbanna,” she said.

The ‘smog-bowl’ states

Beijing, Tianjin and Hebei are home to nearly 10% of China’s 1.4 billion people — about six times the population of the New York City metropolitan area. And despite government efforts to cut emissions — including phasing out polluting industries, retiring old vehicles and replacing dirty coal with cleaner natural gas — the region is frequently smothered by chronic air pollution in winter.

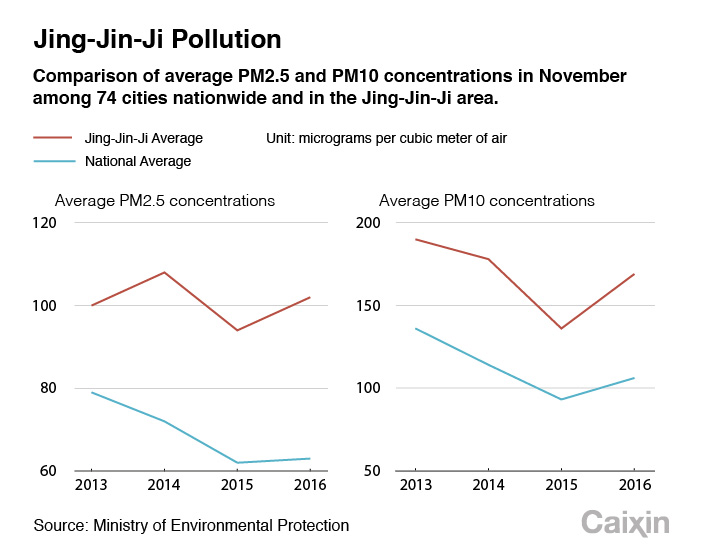

The average concentration of fine, cancer-causing PM2.5 in the air in the Jing-Jin-Ji area in November has not dropped in the past four years, hovering at around 100 micrograms per cubic meter, data from the Minister of Environmental Protection showed.

|

Environmental Protection Minister Chen Jining blamed the problem on the huge amount of coal used to power winter heating systems in the area and the concentration of heavy industries that are high emitters.

Six provinces and municipalities in northern China — Beijing, Tianjin, Hebei, Henan, Shanxi and Shandong — account for only 7.2% of the country’s total area but consume one-third of the coal, Chen said.

The six also accounted for 43% of the country’s steel production, half of the coke output and 20% of cement manufacturing, according to government statistics.

|

The amount of toxic pollutants usually goes up by 30% in the Jing-Jin-Ji area when citywide heating systems are turned on, according to an estimate by the ministry.

Private homes, small restaurants and hotels in the area add to the woes by burning 40 million tons of low-quality coal each year, the ministry said. That’s one-fifth of the annual national consumption. Low-quality coal emits 10 times the pollutants of industry-grade coal used by power generators.

So have government efforts to clean up air in and around the capital failed, or does progress require more time?

China rolled out a national clean-air action plan in September 2012. The government pledged 10 billion yuan ($1.5 billion) to a smog-fighting fund in 2014, with the money distributed to nine provincial-level governments in the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region and the Yangtze and Pearl River deltas.

Under that plan, about 800,000 households in the Jing-Jin-Ji area were told to switch from using coal to natural gas or electricity to power their heating systems in 2016. This has cut the consumption of low-quality coal by 2 million tons. But that’s just a 5% reduction compared to the total.

Nearly 4 million old clunkers spewing carbon and sulfur dioxide were also removed from roads in the area in the last four years, said Liu Binjiang, a department head overseeing air pollution control at the ministry.

In Beijing alone, such initiatives cost the city government 16.54 billion yuan last year.

In the Chinese capital, the average annual PM2.5 concentration level dropped 18% to 73 micrograms per cubic meter of air from 2013 to 2016. In the entire Jing-Jin-Ji area, it has dropped by a third, to 71 micrograms per cubic meter of air over the same period.

But the gray pall hanging over Beijing and its two sister regions in winter hasn’t lifted.

The level of PM2.5 particles shot up to 135 micrograms per cubic meter from Nov. 15 to Dec. 31, which was 2.4 times the average during the other three seasons, data from the Ministry of Environmental Protection showed. Five bouts of smog were recorded in December alone.

Winter blues

Ji Tao, a postgraduate student who has lived in Beijing for seven years, said he did not feel any improvement. “Smog last year was just as bad as it was in 2015, and it smells the same,” he said.

Another long-term Beijing resident told Caixin that she felt air quality has deteriorated because toxic spells had become more frequent and lasted longer in 2016 than it did in 2015. She said she was depressed by the foul air during New Year’s. “You almost couldn’t see your fingers when you stretched out your arms in front of your face,” she said.

The two rounds of smog in late December and earlier January were as severe as the levels of air pollution recorded in January 2013 and February 2014 and again in December 2015 and lasted as long as those previous bouts, said Dr. Wang Yuesi from the Institute of Atmospheric Physics at the Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Although air in Beijing and its surrounding areas has notably improved for most of a year, “it’s no wonder the public don’t feel the change given the ghastly choking spells in winter,” he said.

Unfavorable weather conditions in recent years including warmer winters and the lack strong winds to blow out pollutants have also made the battle against smog even harder to win, Chen said.

The average wind speed in December was 19% lower than the 30-year average between 1981 and 2010, said Wang from the Institute of Atmospheric Physics.

Some residents who are frustrated over the slow progress are going the extra mile to hold the government accountable.

Sun Hongbin, an activist from Hebei, is suing the city government in Zhengzhou, the provincial capital, demanding 32 yuan for the anti-smog mask he bought to protect himself from toxic air while on business trip to the city on Nov. 20.

The 25-year-old claimed that the regional government should be responsible for the high level of toxins on the day rates as “heavily polluted.” The lawsuit, which caused a public stir when it was filed on Nov. 25, is still ongoing.

This lawsuit is not just a random outburst, but a sign that the public was now ready to hold authorities accountable for the poor air, said Ma Zhong, dean of Renmin University’s School of Environmental Studies.

Even on days with a “red alert” for smog, factories continue with business as usual, despite orders to cut production and some cities light tons of fireworks during the Lunar New Year, he said.

“The failure to rein in smog in China lies in the lack of an effective accountability system,” he added.

Contact reporter Li Rongde (rongdeli@caixin.com)

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR