The Silver Way: How Mexican Silver Coins Paved a 16th-Century Sea Route to China

Many Americans think Chinese immigration to the continent started with their country’s railroad projects in the 19th century. But long before San Francisco’s fabled Chinatown, 16th-century Mexico City was home to a sizable Chinese population, and a Pacific trade route to and from Spanish America had turned China into the “factory of the world” 400 years ago.

The sea route that brought most of the silver coins needed to fuel the Chinese economy for nearly 250 years, starting in the mid-15th century, has been long forgotten by the Chinese- and English-speaking worlds, both because the route may have precipitated the fall of the Ming Dynasty in 1644 and because it was overwritten by Anglo-American narratives.

But a new book, The Silver Way: China, Spanish America and the Birth of Globalization, 1565-1815 (Penguin Random House North Asia) — by Hong Kong International Literary Festival founder Peter Gordon and Juan José Morales, a former president of the Spanish Chamber of Commerce in the city — shows that long before the greenback, the Spanish dollar minted in Mexico served as “the first global currency that supported trans-Pacific trade.”

The authors also trace the roots of globalization to the Manila galleons — silver-laden ships that traveled once a year from Acapulco in Mexico to the Philippines from 1565 to 1815 — and not to the sooty Industrial Revolution in Britain in the 18th century.

Europeans who knocked on the doors of the Middle Kingdom in the 15th century found they had nothing that interested the Chinese, except for one thing — silver.

China by the 15th century had adopted silver as the medium to pay taxes and civil servants, but it didn’t have an adequate supply of the metal, according to Morales. The governor of the Philippines at the time, Juan Niño de Tabora, wrote to the Spanish king in 1628 that, for the Chinese, “their god is silver, and their religion the various ways that they have of gaining it.”

If that was so, the Chinese god lived up a mountain in the Andes, in a great mine discovered in 1545 in what is now Bolivia, according to the authors of The Silver Way.

|

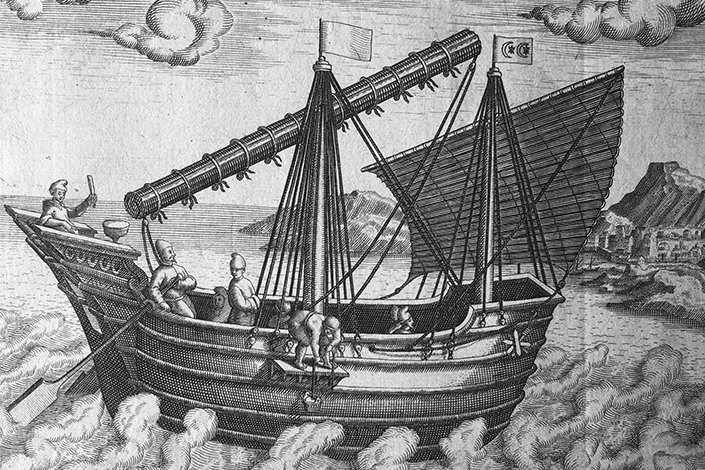

This 1602 illustration by Theodore de Bry, titled “Navigational Vessel of China,” is one of the earliest Western depictions of a junk boat. Photo: Latin edition of Les Grandes Voyages |

The adventurous friar

Andres de Urdaneta had come in search of nutmeg and clove and was shipwrecked. He had been studying the winds and plotting a way to return for nearly a decade when in 1529 the pope decided to draw a line that separated the world into two spheres of influence. East of the line —drawn near the Cape Verde Islands and including Africa all the way to Indonesia — would come under Portuguese influence. West of the line, namely the Americas, would be controlled by the Spanish. And the Spanish emperor, Charles V, “sold” the Spice islands — where Urdaneta was stranded — to the Portuguese for 350,000 gold ducats to fill his war chest, completing the imaginary boundary.

The Portuguese took Urdaneta to Lisbon, threw him in jail and stripped him of all his maps, fearing that if he succeeded in finding a way back from Southeast Asia to Latin America, it could destroy their monopoly in the global spice trade. But the Spaniard escaped to Madrid, redrew the maps from memory and handed them over to the king. He then left for Mexico and took up robes as an Augustine friar.

But the price of pepper and cloves in Spain began rising soon after, and the country’s new king, Philip II, wanted another chance at cracking the spice trade. Several sailors under the Spanish flag, including Christopher Columbus, had tried to discover a route to the Orient, but no one had returned from the Spice Islands through the Pacific Ocean. Urdaneta then was enlisted for another expedition, which in February 1565 led to the establishment of the Philippines as Spain’s trading outpost in Asia — and to the priest completing the first successful trans-Pacific voyage eight months later, opening the floodgates for trade between Asia — including China — and Latin America.

|

A map of China by Jodocus Hondius of Amsterdam, made in 1607, is a replica of the first modern map of China, made by Abraham Ortelius in 1584. Photo: Courtesy Juan Jose Morales |

Silver came from Acapulco to Manila, and Chinese silks, porcelain and lacquerware, and Indian cottons and spices flowed back. The world economy started to integrate through silver, according to Morales.

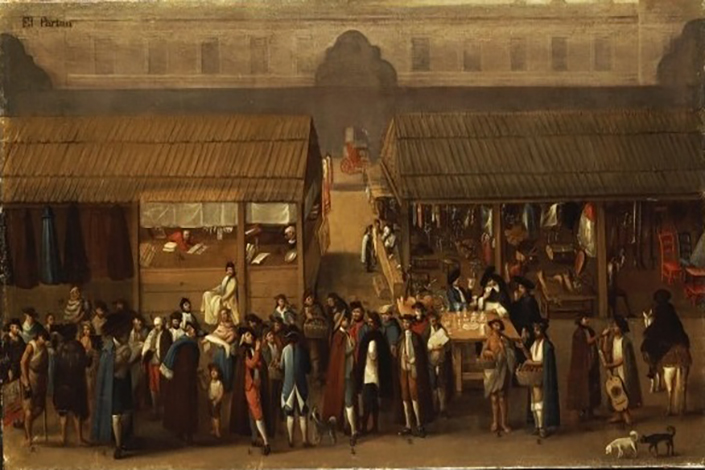

“Inflation or contraction of the silver supply could affect the economies in China or Europe. And there was also a large flow of immigration, particularly from Fujian, first to Manila and from there to Mexico City,” he said. And this gave rise to a bustling Chinese market in the heart of 16th-century Mexico City.

“Even a generic term for ‘market’ in Spanish, ‘parián,’ was derived from the name given to the Chinese market located in the main square in Mexico City at the time,” says co-author Gordon.

|

Spanish King Charles IV is portrayed on a 1798 Mexican dollar, known by the Chinese as "Buddha heads" due to the perceived resemblance of the busts of the Spanish monarchs to images of the Buddha. Photo: Courtesy Juan Jose Morales |

China’s influence on Spanish America spread quickly from fashion to pottery. A southern Spanish fashion symbol, the Manila shawl, originated in Guangdong. Mexico’s main pottery hub in Puebla emulated the Chinese blue-and-white style.

China even began making products exclusively for the Latin American market. One example was a porcelain remake of a traditional coconut-shell cup, known as a “jícaras,” used for drinking chocolate — a fad in South America long before it was in vogue in Europe.

“But complaints about immigrants stealing jobs also existed back then,” Gordon said.

|

A "jícara" is a cup for drinking chocolate made to order for the Latin American market by Chinese artisans. Photo: Museo Nacional de Artes Decorativas in Madrid |

In 1635, the Mexican municipal council received a complaint from the Spaniards about Chinese barbers, who were allegedly undercutting prices. “The municipal council pushed out all the Chinese barbers into the suburbs, but after a year, they were all back,” said Gordon. “In 1667, there were more than 100 (mostly unlicensed) Asian barbershops operating within Mexico City,” he wrote.

An example of a similar rivalry can be found in a 1590 letter by Bishop Domingo Salazar to Philip II, in which the bishop tells the story of a Spanish book-binder who lost his business to his Chinese apprentice after the latter secretly mastered the art and set up shop.

“I assure your majesty that… he (the Chinese worker) has become so excellent a workman,” wrote the bishop. “His work is so good that there is no need of the Spanish tradesman.”

But the Chinese weren’t always good at sniffing out business opportunities. One account by the Jesuit priest Diego de Bobadilla, written in 1640, portrays a woodworker who caught onto the “wrong” fad.

“In the 1590s, there was a Spaniard who lost his nose in a sword fight in the Philippines, and he contracted a Chinese woodworker to whittle him a new nose,” said Gordon. “It was so perfect that he would go to parties and show off his nose. And the Chinese woodworker thought he was onto something big, so the next year he came back with a trunk full of wooden noses. So there were ‘slight’ miscalculations.”

The trade and migration also led to curiosity about Chinese culture.

|

"The Silver Way: China, Spanish America and the Birth of Globalization, 1565-1815" by Peter Gordon and Juan Jose Morales is published by Penguin Random House North Asia. |

It was Martin de Rada, the first Spanish ambassador to China, in 1575, who realized that Marco Polo’s Cathay was actually China, solving a riddle that had puzzled Europe for ages, according to Morales. It was Spaniard Juan González de Mendoza who published a book about China after Marco Polo, which was immediately translated into English, Dutch, German and other major European languages, and remained a best-seller for decades.

The first translation of a classical Chinese text into a European language was also into Spanish — the Confucian text Mingxin baojian, translated by Juan Cobo with the aid of a Chinese scholar and published in Manila in 1593. “It was printed, interestingly enough, using the Chinese method of woodblocks,” said Morales.

But the Manila galleons that plied the trans-Atlantic route for 250 years supporting this knowledge exchange ceased in 1815, at the height of the Mexican War of Independence, and it was slowly forgotten.

Or was it?

New Silver Way

“It was the English-speaking people who forgot,” said Gordon. “The Spanish-speakers never did. The story of early globalization during the Manila galleons was slowly replaced by a new narrative — that of the Industrial Revolution, the Enlightenment and laissez-faire capitalism. It’s a narrative that has very clear philosophical underpinnings: liberal political systems, the rule of law, and as you move forward it becomes very much the Anglo-Saxon political-economic philosophy.”

But this post-Adam Smith model fails to explain the rise of China. “So, to really understand where we are now, you have to expand the data set back to 1565,” Gordon said. “This earlier period of globalization wasn’t dominated by one party or the other,” and trade progressed without any international institutions to support it.

At a time when China is trying to rekindle old ties and revive ancient trade routes, especially under its trillion-dollar “Belt and Road” initiative, the authors of The Silver Way believe revisiting this old model may hold clues to where the world is heading.

“In the English-speaking world, in books and magazines, when people ask what will happen in a case when China and the United States aren’t the best of friends, the examples of what might happen are taken from the darkest days of the 20th century,” Gordon said. “So you hear words like ‘the new Cold War.’”

But a longer view of history may offer alternative models by showing how Asia and the Americas collaborated even before New York existed.

“China is very active in Latin America today. At last year’s Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation meeting in Lima (Peru), when it was clear that the United States would pull out of the Trans-Pacific Partnership, there were alternatives being proposed which didn’t involve the U.S.,” said Gordon, who sees this as a harbinger.

“And something that was not widely reported in the English-language press was that on his way home, President Xi Jinping stopped in the Canary Islands to meet with the vice president of Spain, and they discussed Sino-Spanish collaboration for projects in South America — which has echoes of The Silver Way, ” he said.

Contact reporter Poornima Weerasekara (poornima@caixin.com)