Can Services Save China?

(Beijing) — Developing China’s services sector has played a key part in government strategy to shift the country’s economy to a model based on consumption and away from the credit-fueled investment and export-led growth that propelled its expansion for three decades.

A milestone was reached in 2013 when services, also known as the tertiary sector, became the biggest part of the economy, accounting for 46.7% of gross domestic product (GDP), compared with 44% for the secondary sector and almost double its 23.9% share in 1978, when China embarked on its reform and opening-up policy. (See graphic “Share of Value-Added Output in GDP.”)

|

The services sector is also the biggest employer, accounting for 43.5%, or 337.6 million, of the total workforce of 776 million in 2016, and compared with 28.8% for the secondary industry. Data from the National Bureau of Statistics show that from 2012 to 2016, services-sector employment rose by 60.67 million, while employment in agriculture fell by 42.8 million and in the secondary sector by 8.91 million.

But economists say size alone may not be enough to ensure that services can truly become a growth driver without government action to open up markets dominated by the state-owned sector to the private sector, boost competition, do more to support innovation, and get rid of distortions such as tax incentives that benefit industry at the expense of services. Boosting demand and supply of services such as education, health care, logistics and tourism may transform the structure of the economy in terms of size and composition, but it won’t necessarily create the kind of high-wage, high-productivity jobs needed to sustain a relatively fast rate of GDP growth.

“Economic structural transformation hinges on the strength of the services sector rather than its size,” said Raymond Yeung, chief Greater China economist at Australia and New Zealand Banking Group. “The rising share of services in GDP does not guarantee the economy will grow in a sustainable and stable way. The contribution of services to economic growth hinges on its efficiency rather than its share.”

The key to increasing incomes and thus consumption is raising productivity, the amount of output each worker in the labor force produces. If companies can produce more with the same amount of resources, or produce the same with less, they will increase their profits and should increase wages, which boosts demand and economic growth.

Low productivity

The problem for China is that it’s still stuck in low-end, labor-intensive and low-productivity services.

Lu Zhengwei, chief economist at China’s Industrial Bank, points out that “the increasing share of the services sector has been largely due to the growth of traditional services such as wholesale and retail trades, which continue to account for the largest share of services’ value-added output.”

Data from the National Bureau of Statistics show that the wholesale and retail trades still accounted for the biggest share of services value-added output in 2016, almost unchanged from a decade earlier. In second place is financial services, which has shown the biggest growth, jumping to 16% from 13.1% over the last 10 years. Real estate is third with a share of 12.5%, up from 11.9% 10 years ago.

A study published in 2016 by the East-West Center, a U.S. think tank, said that China has made progress in shifting from traditional services to high-end, knowledge-intensive services such as finance, information transmission, computer services, software, legal and technical services: The share of high-end services in total service sector output increased from 27.3% in 1991 to 39.9% in 2011. But in 2011, China was still lagging behind other upper-middle-income countries like Malaysia and Thailand, where high-end services accounted for about 45% of the services sector.

Taking China’s GDP per capita into consideration, the share of services in GDP was 46.1% in 2013, about 13 percentage points lower than an economy would typically reach at that level of GDP per capita, according to a working paper prepared by Liu Tao and Wang Wei at the Development Research Center, a think tank under the State Council, in 2015.

There are many reasons why China is lagging behind. Zhang Bin, a researcher from the Institute of World Economics and Politics at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), said one important factor is that state-owned enterprises (SOEs) that are protected by preferential policies still dominate many middle-to-high-end services, including aviation, post and communications, financing, leisure, culture and social services. Market access for private and foreign companies has been limited until relatively recently.

Government data show that while SOEs account for only 8% of fixed-asset investment in manufacturing, they account for 43% of investment in the services sector, although that’s down from 57% in 2004. A report by the McKinsey Global Institute, a U.S. think tank, in 2016 said that continued domination by SOEs leads to limited competition, a lack of motivation to innovate, and limited choices for consumers.

Growth in services has also been hindered because government policies, including taxation, traditionally favored capital investment and manufacturing, which were better at boosting GDP and also were the backbone of the country’s massive export machine.

The government has for many years been aware of the problems and the steps it needed to take to address them — including deregulation, opening up markets to competition, reducing barriers to entry, cutting red tape, giving private companies better access to funding, and offering more incentives and policy support.

In 2005, the State Council, China’s cabinet, issued a document containing 36 policy measures to attract nonstate capital into services industries, including aviation and opening them up to competition. The document was updated in 2010 with more-specific policies to encourage the private sector to invest in 18 industries, including transportation, power, oil and natural gas, telecommunication and finance.

Services innovation

The 13th Five-Year Plan (2016-20), released in 2016, devoted a large section to the tertiary sector and set a soft target for services to account for 56% of GDP by 2020. It pledged to encourage private enterprises to enter more sectors, open up services to foreign competition, improve logistics, and promote high-end services such as industrial design, engineering consulting, insurance and credit ratings. It also reiterated its commitment to open up more sectors to “nongovernmental capital,” including civil aviation, banking, education and logistics.

In June, the National Development and Reform Commission, the country’s economic planning agency, released a policy document, “Outline of Innovation and Development of Services Industry for 2017 to 2025,” with a focus on employment, productivity and policies. Among the targets is increasing the share of services in GDP to 60% by 2025 and raise the proportion of jobs provided by services industries to 55% of total employment from 43.5% in 2016.

Some industries are opening up, but it’s slow going. The East-West Center report points out that many of the policy measures in the 2005 and 2010 documents have yet to be implemented because relevant laws and regulations haven’t been changed.

Several new private low-cost airlines were established in the mid-2000s, including Shanghai-based Spring Airlines and JuneYao Airlines, and Beijing-based Okay Airways, but they have made little impact on the overall industry. In an interview with the Beijing News in 2012, Spring Airlines Chairman Wang Zhenghua said it took the company six years to get regulatory approval for a red-eye flight from Shanghai to Beijing.

China started a pilot program to open the banking industry to the private sector in 2014. Five licenses were awarded that year, including to WeBank, co-founded by Tencent Holdings; and MyBank, co-founded by Alibaba Group Holding Ltd., two of the country’s largest Internet companies. Last year a further eight private banking licenses were granted.

In 2014, the government issued 11 mobile virtual network operator licenses to private companies, including Alibaba, allowing them to resell mobile services and create packages and features. In a report last year, management consultants McKinsey said these companies have taken less than 1% of the market, and industry reports suggest they have not generated much profit because they lack sufficient bargaining power to obtain a competitive wholesale prices from the three big telecom companies, and their products are not competitive with those of the big three in the retail market.

The need to move China’s services sector up the value chain and improve productivity is becoming more urgent as the economy continues its transition from heavy industry and manufacturing toward services and consumption.

There are several factors involved. Economic history shows that as an economy develops, it naturally shifts from industry and manufacturing to services. When that happens, productivity growth slows because services industries tend to use more labor than capital, so it takes more people to produce one unit of services output than manufacturing output. The way to increase productivity is to get more output out of one person or to get the same output from fewer people. Moving up the value chain to provide services that cost more and employ people at higher wages, such as IT, software or engineering services, should also increase labor productivity.

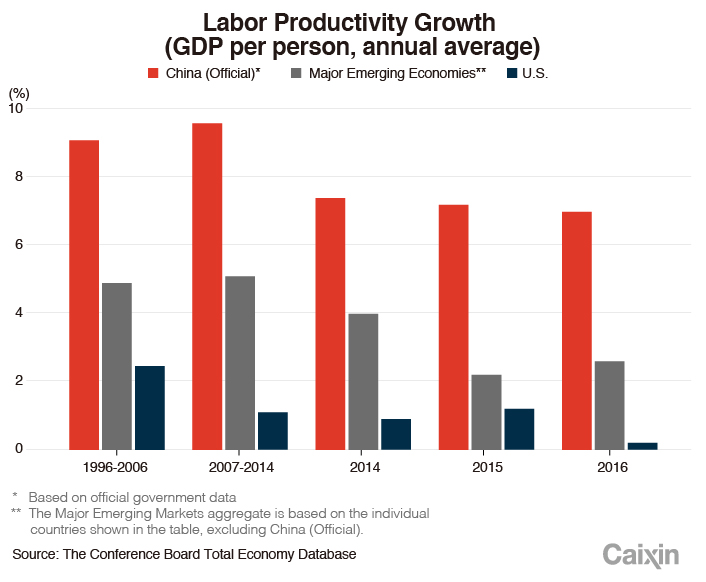

China notched up very high annual rates of growth in labor productivity in the 16 years through 2014, according to data from The Conference Board, a New York-based research group. It calculates that based on official government data, China’s average annual growth in productivity, or GDP per person employed, from 1999 to 2006 was 9.1%, compared with 4.9% for major emerging economies and 2.5% in the United States. That rose to 9.6% from 2007-14, and compared with 5.1% for major emerging markets and 1.1% in the U.S. In 2016, China’s productivity growth declined to 7% compared with a 2.6% increase for major emerging economies and 0.2% in the U.S. (See graphic “Labor Productivity Growth.”)

|

But China was starting from a very low base, and in spite of the impressive growth, productivity is lagging. Although as a middle-income developing economy, China’s productivity could reasonably be expected to be lower than advanced economies such as the U.S., research shows that it is also trailing other countries at similar stages of development. The Conference Board calculates that in 2016, labor productivity in China was just 23% of that in the U.S. based on official data, better than Indonesia, but trailing Thailand, Mexico and Brazil.

Services productivity is even more of a problem. In 2012, China’s labor productivity in services was only equivalent to about 34% to 66% of that in Brazil, Mexico and Peru, 49% of that in Malaysia and 82% of that in Thailand, according to World Bank data.

On the one hand, that gives China a lot of room to catch up, but on the other hand, it means that if China doesn’t manage to improve its productivity by becoming more efficient and increasing the share of high value-added services, then economic growth, competitiveness and incomes could suffer.

The McKinsey Global Institute estimates that more than 200 million workers may need to shift into other industries by 2030 as the economy goes through its structural shift. It says services industries are likely to provide most of the jobs for displaced workers from traditional manufacturing sectors and for those newly urbanized, potentially employing around 500 million people by 2030, up from 320 million today.

Ensuring the economy can provide jobs for all those people puts even more pressure on the government to push forward with reform, open markets to competition and encourage companies to upgrade to higher value-added services.

There is, however, a danger that China is moving too quickly in its pursuit of a services and consumption-driven economy and that it will deindustrialize too early. This phenomenon, in which developing countries see the share of industrial output in the economy decline before it has reached maturity, could have serious economic consequences, according to Dani Rodrik, a professor of international political economy at Harvard University who is known for his research into the trend. Premature de-industrialization can lead to a sharp growth slowdown, widening inequality and preventing countries from catching up with advanced economies. Roderick said his research shows that Latin American countries have been especially hard hit by this trend.

A working paper prepared for the International Monetary Fund in 2016 by economist Zhang Longmei noted that China has already started to deindustrialize, as the share of the industrial-sector output in GDP peaked in 2011, and the share of industrial employment in total employment peaked in 2012. The turning point happened when China’s GDP per capita was around the same level as that of many other countries when they started deindustrialization. Zhang said that as industrial productivity in China is still much lower than that of advanced economies, there is still need and scope for the country to increase industrial productivity.

In a report last year, HSBC China economists Qu Hongbin and Li Jing pointed out that countries such as South Korea and Singapore started to deindustrialize when their GDP per capita levels were relatively high, which enabled them to catch up with advanced economies. However, countries such as the Philippines, Brazil and Mexico all started to deindustrialize when their respective GDPs per capita were only about 15% of the level of the U.S. and have shown almost no further improvement in GDP per capita since they started to deindustrialize. As China’s GDP per capita was only 14% of the level of the United States in 2015, the economists said it was too early for China to shift toward services-led growth and should continue on the industrialization path but also make its investment more efficient.

Zhang Bin from CASS said that manufacturing and services can both be engines of growth, and that the industrial economy should still be supported and expanded.

“The rising share of the services sector in GDP doesn’t necessarily mean that industry is no longer important,” Zhang said. “The restructuring and upgrading of industrial sectors can bring about increases in salary levels and productivity, which will be an important driving force for the services sector.”

China’s economy grew by an average 10% a year from 1998, after the Asian financial crisis, to 2007, just before the global financial crisis struck, as the government opened up the industrial sector to competition. Hundreds of millions of migrant workers flooded into the cities to work in factories, and China’s entry into the World Trade Organization in 2001 triggered a manufacturing boom that propelled the country into second place in the global economic rankings in terms of absolute size.

The structural transition toward a services-driven economy appears inevitable. The big question now is whether that will unleash the same burst of growth the country experienced during its industrialization, or whether the policies and reforms needed to open up industries to competition and push services up the value chain will fall short and leave China facing a future of low growth and stagnant incomes.

Contact reporter Pan Che (chepan@caixin.com)

- 1Luckin-Backer Centurium Capital to Buy Blue Bottle Coffee From Nestlé

- 2Two Sessions: With 4.5%-5% Growth Target, China Aims to Create Space for Reform

- 3China Business Uncovered Podcast: Brazil’s ‘Very Chinese Moment’

- 4First Tanker Crosses Strait of Hormuz Since Iran’s Closure Threat

- 5War Risk Insurance Returns to Strait of Hormuz — at a Price

- 1Power To The People: Pintec Serves A Booming Consumer Class

- 2Largest hotel group in Europe accepts UnionPay

- 3UnionPay mobile QuickPass debuts in Hong Kong

- 4UnionPay International launches premium catering privilege U Dining Collection

- 5UnionPay International’s U Plan has covered over 1600 stores overseas