The Wake-Up Call for China’s Chip Industry

When Zhang Zhenhui’s plane landed in Dubai on April 16 and his phone lit up with a dozen missed calls, he knew that something terrible had happened.

While Zhang was in the air, the U.S. government had issued a seven-year denial order against Chinese telecom equipment-maker ZTE, preventing the company from buying crucial components from American chip companies. The ban, which has since been lifted, threatened ZTE’s survival and caused it to report a net loss in the first quarter of the year.

The ban also dealt a major personal blow to Zhang, then an executive vice president at ZTE. He was dismissed from ZTE alongside many other company executives as part of the corporate overhaul required by the U.S. government before the ban could be lifted. It was a “truly unwilling and deeply humiliating” departure after 18 years at the company, Zhang said in a farewell letter.

The effect of the 88-day ban against ZTE, one of the world’s largest communications equipment manufacturers, was a serious wake-up call for China’s chip industry, and drew renewed attention to its years-long struggle to catch up with global chip leaders.

Reliance on chip imports

Chinese companies currently rely heavily on chip imports due to a lack of advanced chip production technology in the country combined with high demand from increasingly telecommunications-dependent industries.

When it comes to higher-end central processing units (CPU), field-programmable gate arrays (FPGA), and electronic design automation tools, imports account for as much as 95% of the components used in China, according to Zhu Jing, research director at the Beijing Semiconductor Industry Association.

The lag between chips produced by domestic companies and foreign companies is significant, Zhu said, with domestic CPUs only 30% to 50% as efficient as equivalents produced by U.S. industry leader Intel.

That lag is actually small compared to other parts of the chip industry, since CPUs are considered more important and receive more government funding than other types of chips. “China is catching up when it comes to CPUs, but for areas like graphics processing units and FPGAs, it hasn’t begun to close the gap,” Huang Bowen, an engineer at the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Computing Technology, told Caixin.

Chinese companies’ biggest weakness is in chip manufacturing, rather than design. International players Intel Corp., TSMC Ltd., and Samsung Group have already begun to develop a 7-nanometer process for manufacturing chips, while China’s leading foundry, the Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation (SMIC), has just mastered the 28-nanometer process. The lower the number of the process, the smaller, faster, and more efficient the chips they can produce. SMIC is at least five to ten years behind its overseas counterparts.

|

|

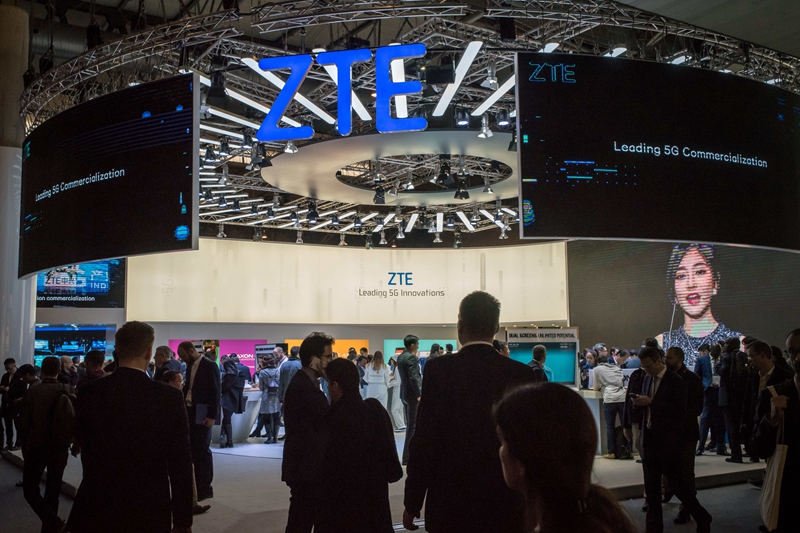

A ZTE booth at the 2018 Mobile World Congress exhibition in Spain in February. An 88-day U.S. ban against the company was a serious wake-up call for China’s chip industry. Photo: VCG |

Chinese-led ecosystem

Some of China’s chip companies and policymakers believe establishing a Chinese-led hardware and software ecosystem is the only way to guarantee that domestic companies will be self-sufficient and able to withstand threats from foreign interests and governments.

Loongson Technology, incubated by the Chinese Academy of Sciences, is one such domestic player. Loongson is one of the few chip-makers in the world that has independently developed its CPUs, on the basis of abstract models developed by American chip designer MIPS. Loongson’s products are used mainly in defense science and technology.

Zhao Weiguo, president of Tsinghua University-controlled chip company Tsinghua Unigroup, originally hoped to build domestic integrated circuit companies from the ground up, but gradually found that this would require huge investment, and expose the country’s nascent chip-makers to overpowering competition from far stronger foreign counterparts.

So Zhao decided to use mergers and acquisitions to consolidate resources and quickly gain new capabilities. Between 2013 and 2014, Tsinghua Unigroup acquired Shanghai-based fabless chip-makers Spreadtrum and RDA Microelectronics for $1.78 billion and $907 million, respectively. In 2015, Hewlett-Packard sold a controlling stake in its China-based H3C Technologies to Tsinghua Unigroup for around $2.5 billion.

Zhao compared succeeding in the chip industry to a dangerous river crossing, telling Caixin the acquisitions of Spreadtrum and RDA Microelectronics in particular were “equivalent to buying the bridgehead on the opposite bank of the river.”

But growing through acquisitions has its downside. As Chinese companies look abroad for new assets, foreign governments are growing increasingly wary of high-tech acquisitions, citing security concerns. Tsinghua Unigroup’s reported recent deal to buy French components-maker Linxens for around $2.6 billion is expected to be a test of French and German regulators’ tolerance for Chinese investment.

Controversial partnerships

Foreign companies are an important source of direct access to technology for many Chinese companies, whether through mergers or joint ventures. But some foreign-Chinese chip partnerships have attracted controversy.

In May 2017, U.S. chip giant Qualcomm announced a joint venture with Chinese state-owned company Datang Telecom Technology, which would focus on the low-end mobile phone chip market. But many in the Chinese chip industry, including Tsinghua Unigroup’s President Zhao, fear that Qualcomm’s ability to produce chips on a large scale and at low cost could threaten domestic companies unable to match Qualcomm’s capacity — a fear that delayed approval of the joint venture until May this year.

Another Chinese partnership involving Qualcomm, this time involving the government of remote Guizhou province, has also raised questions over how beneficial foreign partnerships really are for domestic chip-makers. Qualcomm established Guizhou Huaxintong Semiconductor Technology Co., its joint venture with Guizhou, in January 2016, to produce chips for data servers.

But after a protracted hostile takeover attempt by Singapore-based Broadcom that ended in March, Qualcomm found itself weakened and forced to cut expenditure in the server chip sector in order to meet shareholders’ demands — causing worry that it would withdraw support from Huaxintong.

There are two major risks for Chinese companies acquiring technology through foreign joint ventures, according to Gu Wenjun, chief analyst at industry research company ICWise. Firstly, foreign companies are not interested in cultivating competitors, so they will never transfer core technologies to Chinese joint ventures. Some companies are actually forbidden by other governments’ from handing their most advanced technologies over to China.

Secondly, while many Chinese companies may be able to master existing technologies through joint ventures, they may have the ability to independently progress onto next generation processes, and may also be dependent on authorization from their foreign partners to use new technologies, Gu said.

Wake-up call

Industry observers expect a flood of capital into the domestic chip industry in response to the shock of the recent ZTE ban.

The government-led China Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund is in the process of a massive 150 billion yuan ($22 billion) fundraising round, while private companies like internet giant Alibaba Group Holding Ltd. and even household appliances maker Gree Electric Appliances Inc. pledging their support for and willingness to invest billions of yuan in the chip industry.

The Chinese government has offered policy support to the chip industry from as early as 2000, with the aim of helping Chinese companies catch up despite chip technology transfer restrictions put into place by many developed countries. But, in the past, “the government believed that we could develop the integrated circuit industry through the market allocation of resources, but that is actually not feasible,” said Wei Shaojun, the director of Tsinghua University’s Institute of Microelectronics.

Chips are a high-risk industry, compared to internet companies, and “as long as all other things are more likely to generate returns and higher profits than chips, investors will be few or mainly government-led,” Zhang Suyang, a partner at Volcanic Venture, a fund investing in smart technologies, said at a forum in April.

The Chinese government should continue to provide extensive support for areas like memory chips, which involve high technical standards and large capital input, as well as long investment cycles, Zhu Jing from the Beijing Semiconductor Industry Association said.

At the same time, China’s educational institutions should elevate microelectronics to the status of a top-level discipline, and increase enrollment through scholarships in order to provide a larger talent pool for the domestic chip industry, ICWise’s Gu said.

Contact reporter Teng Jing Xuan (jingxuanteng@caixin.com)

- 1Cover Story: China Carves Out a Narrow Path for Offshore Asset Tokenization

- 2Drownings Shake Chinese Enthusiasm for Travel to Russia

- 3Over Half of China’s Provinces Cut Revenue Targets

- 4Li Ka-Shing’s Port Empire Hit by Forced Takeover Amid Panama Legal Dispute

- 5China Business Uncovered Podcast: A $15 Billion Bitcoin Seizure and the Fall of a Cybercrime Kingpin

- 1Power To The People: Pintec Serves A Booming Consumer Class

- 2Largest hotel group in Europe accepts UnionPay

- 3UnionPay mobile QuickPass debuts in Hong Kong

- 4UnionPay International launches premium catering privilege U Dining Collection

- 5UnionPay International’s U Plan has covered over 1600 stores overseas