In Depth: China’s Social Security Balancing Act

* China’s pension fund faces a widening shortfall as the population ages

* Social insurance collection overhaul intended to close loopholes sparks concerns over rising business costs

Chinese policymakers are walking a tightrope between an emerging pension shortfall as the population ages and concerns that toughening collection of social insurance levies will hurt businesses just as economic growth is slowing.

The threat of a pension shortfall is imminent as the population greys. In 2017, China’s pension funds collected 3.3 trillion yuan ($515 billion) and handed out 2.9 trillion yuan in payments. But the system avoided going into deficit mainly because of subsidies from the central government, official data showed.

At stake are hundreds of millions of retirees who rely heavily on the pension fund for a living.

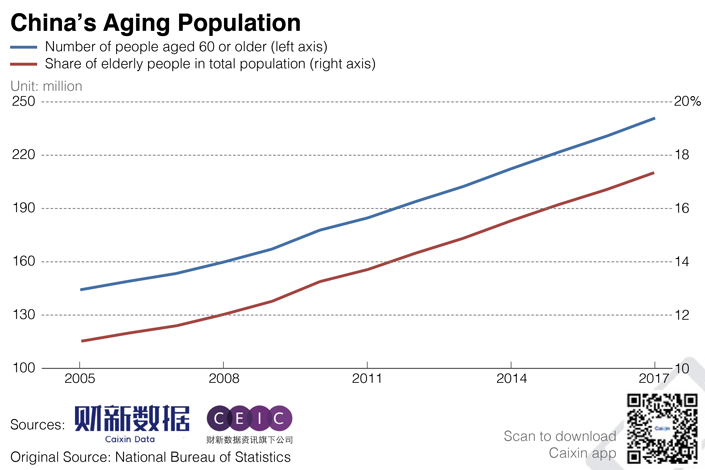

The challenge to make ends meet is ever growing because of China’s rapidly aging population and declining birth rate. At the end of 2017, China had 241 million people over the age of 60, or more than one in every six of the country’s 1.4 billion people. By 2050, one of every three Chinese will be over 60, according to the United Nations. Meanwhile, the number of newborns fell by 3.5% in 2017 to 17.23 million, despite the end of the one-child policy.

Policymakers have stepped up efforts to shore up the pension fund and strengthen the entire social security network, introducing measures such as transferring shares of state-owned enterprises to retirement funds and building up a commercial pension market to provide more channels for individuals to save for retirement.

Now the central government is preparing an overhaul of the mechanism for collecting social insurance levies. China’s pension funds are controlled by provincial-level governments, but the responsibilities for collecting the levies are inconsistently distributed between taxation and social security authorities. Under the new system, power to collect the funds will be consolidated in taxation departments to seal loopholes enabling evasion and make collections more transparent and efficient.

|

The new rules may lead to a wave of small business closures because of higher costs and will put companies under closer scrutiny by tax officials, critics say. If all companies are required to fully meet their social insurance payment obligations, the average costs for businesses will increase by 30%, according to Wang Dehua, a financial analyst at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS), a top think tank.

Under Chinese law, employers are obligated to make payments to help provide basic social insurance for employees, including pensions, medical care, unemployment benefits, work- injury coverage, maternity and the housing provident fund, which helps workers cover their rent and home purchase. Contributions for pensions vary among regions and range from 13% to 20% of employees’ wages. Workers pay 8%.

Total social insurance payments by Chinese employers and employees amount to 39.5% of payrolls, a rate higher than in many other countries. In 2014, the average rate of OECD, a group of mostly rich countries, was 29%, according to China Social Security Journal.

To reduce costs, it is common for employers to find ways to avoid making the full contributions, for example by dividing compensation into basic wages and bonuses, paying taxes only on basic wages, or by hiring more temporary workers to skirt social security obligations.

Some companies have struggled with the payments amid rising labor costs and slowing business. In July, China’s largest telecom equipment maker, Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd., cut its payment to the housing provident funds in several cities from over 10% of wages to 5%, the lower limit of a national standard. Analysts said Huawei made the move to cut labor costs.

The dilemma is testing China’s policymakers as they seek a balance between efforts to expand social insurance revenue and to allow businesses to thrive, analysts said.

While ensuring that all employers pay their contributions according to law, regulators should also consider lowering the contribution rate to alleviate pressure on businesses, said Yu Qingquan, chief executive officer of social insurance information provider 51Shebao. Other experts said that making China’s social security system sustainable will require systemic reform and introduction of more sophisticated management of both collection and spending.

Closing loopholes

With provinces’ collection of social insurance levies split between tax and social security authorities, the duties of the departments often are not clearly defined. Coordination and information-sharing are also poor, according to Wang Yanzhong, a CASS professor who conducted a nationwide survey of the local social insurance system between 2016 and 2017.

The methods of tax calculation also vary across regions. Some local authorities have offered preferential policies or reduced social insurance payment requirements to attract investment, Wang said.

That has left some employers leeway to minimize payments by underreporting their wage payments or workforce size, experts say.

A survey by 51Shebao this year found that only 27% of companies have made full payment of their share of social insurance contributions, while 31% paid at the bottom of the range of national standards leaving their employees with the least insurance coverage, according to a research paper published Aug. 24.

“Taxation departments have comprehensive information about companies’ business operations, and it is possible for taxation authorities to require companies to fully fulfill their social insurance obligation,” CASS’s Wang Dehua said.

Official data back him up. In Guangzhou, where social insurance payments are already collected by tax departments, more than 90% of registered business taxpayers reported social insurance payments in 2015. In Beijing, where social security departments are in charge of the collection, the figure was only 42.9%.

Under the government’s reform plan, taxation departments across the country will finish building systems in preparation for taking over collection tasks by Dec. 10 and will start their new duties Jan. 1. In addition, social security department will connect their systems with taxation departments to share information and jointly deal with disputes.

Pension shortfall

China’s basic pension insurance fund is a crucial part of the country’s social insurance system as it accounted nearly 70% of the entire national social insurance collection in 2017, according to figures from the Ministry of Human Resources and Social Security.

While the fund had an aggregate surplus of 4.1 trillion yuan in 2017, that mainly reflected government subsidies, according to CASS professor Zheng Bingwen. Subsidies accounted for 15% of nationwide fund gains in 2016. Without them, the system would have been in the red since 2014, according to an actuarial team led by Zheng.

Without subsidies, China’s pension funds will post deficits widening from 234 billion yuan this year to 534 billion yuan by 2022, according to Zheng’s team.

In some provinces, local pension funds have already been running deficits. The pension fund of the northeastern rust-belt province of Heilongjiang was in the red by more than 23.2 billion yuan in 2016, according to official reports.

To help out regions struggling with pension deficits, the central government in July created a national pool to take a portion of money from provincial-level pension funds and redistribute the money among regions. The government said this centrally controlled pool will balance pension-fund burdens across the country and strengthen the overall system.

The centrally controlled pool is the first step for China to address the country’s fragmented pension system and huge imbalances between poorer and wealthier provinces, CASS’s Wang Dehua said. Yu at 51Shebao said compulsory transfers to the central government fund will also encourage local authorities to tighten scrutiny of companies’ pension payments.

As governments step up collection efforts, policymakers should carefully control the strength and pace of new policies to avoid excessive impacts on businesses, Wang Dehua said.

In addition to tightening collections, China should also push forward reforms in social insurance fund management and spending, other analysts said. Lou Jiwei, former finance minister and current chair of the National Council for Social Security Fund, said social insurance policy design should take into consideration various factors such as demographic change and population mobility and set up a system based on actuarial balance.

“China has a high social insurance contribution rate but still can’t reach a balance. Despite the aging population issue, it also reflects inappropriate incentive mechanisms,” Lou said.

Contact reporter Han Wei (weihan@caixin.com)