Why The New York Times Said ‘No’ to Apple News

Taking his Android phone out of his suit pocket, 62-year-old Mark Thompson noted the many news apps on his phone: The New York Times, the Wall Street Journal, The Economist, The Guardian and more.

“I always say to people, if you’re serious about news, get multiple perspectives and different publishers,” he said. “I’m also interested in what my competitors have to say because that list of competitors, they’re all great news organizations and they do great journalism.”

Thompson worked at the BBC for 33 years in total before becoming CEO of The New York Times in 2012. Since then, the number of subscribers has increased fourfold.

Apple’s recent launch of a subscriber-based news service has triggered strong reactions from the media industry — including The New York Times.

Journalism’s savior?

Within 48 hours of launching on March 25, Apple News+ had over 200,000 subscribers, according to a New York Times employee.

The app acts as a one-stop shop for news, with users paying a monthly fee to access material from over 300 publications.

Apple has long said that it wants to help “save journalism,” and believes its huge user base can help the declining paper media industry expand subscriptions and readership online. However, not all traditional media organizations have been enthusiastic.

Most of the outlets taking part are magazines, but Apple also has three major newspapers on board: The Wall Street Journal, the L.A. Times, and the Toronto Star. All three anticipate that the partnership could expand subscription numbers.

But two of America’s most influential papers, The New York Times and the Washington Post, are not participating. These classic brands may be worried that Apple is not saving news — but subverting it.

|

Humans or algorithms?

As one of America’s oldest and most influential papers, The New York Times has cooperated with online platforms such as Google and Facebook. When Apple launched Apple News in 2015, the Times joined as a content provider.

Thompson believes that one of the major problems with Apple’s new platform is the “jumbling of news from lots of different sources,” especially in the age of “fake news.”

“News is not like music. You can listen on Spotify to a set of suggested tracks and it doesn’t matter where they come from — what matters is whether you like the sound of it,” he said. “News is different. It’s provenance. Who made it and whether you can believe it or not really matters.”

Another problem is its challenge to how the media decides what’s important.

Today, media and tech companies use algorithms to understand reader preferences and push more relevant content, but this completely “user-oriented” presentation breaks the news media’s ability to present what news is most important, Thompson said.

“I think the top news on the home screen should be selected by humans,” he said, but noted that there should be a balance between what readers should know and what they like. It would be difficult to “ask a piece of AI to parse the overall significance of a news story. That’s a very, very sophisticated judgement,” he said.

Worries about the model

News organizations may hope that tech platforms can help expand their influence, but they also recognize that they lose some ownership of their content.

“We like distributing our journalism very widely,” Thompson said. “But we really want people to become used to using our apps, our website.” Speaking to Reuters before the launch of Apple News+, Thompson likened the platform to Netflix, saying that it was monopolizing content distribution.

Thompson’s worry is not without reason. At first, Netflix shelled out for rights to stream movies and shows and is now producing its own content.

The New York Times also worries that a third-party mediator will alter the relationship with users. Apple News+ is a closed system, where users don’t have to change apps to read articles from different sources. This was a big selling point for protecting user privacy because Apple can see how many clicks an article got but not who read it. It also doesn’t allow advertisers to track user information.

However, this means that advertisers can’t learn about users’ reading preferences, which also blocks content providers from learning about their readers. This makes it harder to find new subscribers through Apple News+.

“We want to be able to email our users and develop a relationship with them. And we don’t really want anyone between us and that,” Thompson said.

Splitting income

The most controversial point of Apple News+ is that it might hurt the media’s “subscription model,” where revenue is driven primarily by subscription fees rather than by advertising. The Apple News+ monthly fee is only $9.99, lower than a standard digital subscription to The New York Times, which is $15 per month.

According to the Wall Street Journal, Apple will take half the subscription revenue and distribute the remainder to its partners depending on the traffic and the length of time spent on each article. Taking into account the number of magazines and newspapers that have signed up to the service, each outlet is unlikely to receive the same revenue obtained through subscriptions on their own dedicated site or app.

Thompson believes the key to successful cooperation between media and tech platforms is mastering the relationship between the business model and the users. Currently, the economic benefits of cooperation are not going to publishers, he said.

Thompson declined to comment on ongoing negotiations between The New York Times and Apple. However, Thompson stressed repeatedly that The New York Times does not exclude the prospect of collaboration with other platforms, citing Snapchat. “We had a financial arrangement and we made a very visual version of The Times for Snapchat for a period of time,” he said. “When there's a different audience or there’s a particular creative proposition, we’re not against in principle working with platforms.”

Read more

New York Times publisher A.G. Sulzberger touts future of digital journalism

He also spoke of the paper’s ongoing collaboration and negotiations with Google. After The New York Times erected a “soft” paywall in 2011, users could search for articles in The New York Times on Google and read three free articles per day before they hit the paywall. This allowed users to read up to 90 articles for free per month, much more than the now only five-article allowance dictated by the Times. “Google has changed that and now they allow us to adopt our pay model in Google search,” he said, touting a successful lobbying campaign by the Times and other outlets.

“We’re working together to develop ways to make it easy for people who are using Google to subscribe,” Thompson added. “Google is an example of a platform that tries to understand what we need to get our business to work. That’s an example of a good collaboration.

Invest in journalism

News organizations may turn to platforms to adapt to new technologies while trying to also transform their business models.

The New York Times strategy for the future is simple, Thompson said: keep investing in good journalism.

“Most other news organizations are cutting journalists now. I don't see how you create successful journalism business if you don’t invest in your products,” he said. The New York Times has increased its investment in investigative journalism, as well as into cross-discipline reporting. For example, when the Boeing 737 Max crashed in Ethiopia, it began as an aerospace story, but quickly turned into a political story and a business story about the global competition between Boeing and Airbus, he said.

Thompson also spoke of the newspaper’s emphasis on appealing to young readers, citing the “The Daily” podcast as an example. It was the most-downloaded podcast on iTunes in 2018. “46% of the audience is 30 years old or younger,” he said. “I think we’re doing a better job of getting younger people to connect with news than many of the new digital publishers.”

Thus, the newspaper is also working to help readers to understand the process behind the news, especially amid accusations of “fake news” from U.S. President Donald Trump. In June this year, The New York Times will launch a weekly TV show showcasing how their journalists report news.

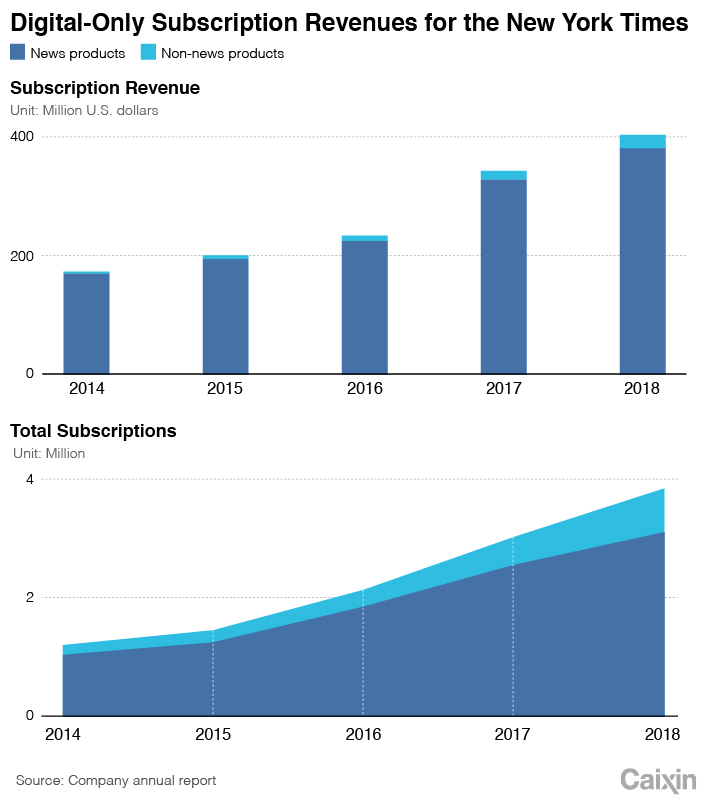

So far, The New York Times’s strategy is working — according to the organization’s annual financial report released in February, total revenue in 2018 reached $1.749 billion, up 4.4% from 2017. Advertising revenue was almost the same, but net revenue from digital subscriptions increased 17.7% to $401 million, and the number of subscribers to various digital products reached 2.26 million, including 2.71 million subscribers to digital news, a 21.6% increase.

However, operating profit decreased by 17.5 percent, to $75 million, and total subscription revenue increased by only 3.4%, reflecting the poor performance of print newspaper subscriptions. Thompson said that the print business will continue until it ceases to contribute positive margins.

In the age of the internet, The New York Times hopes to use high-quality original content to enhance its competitiveness and bargaining power. The ambitious Thompson has also set a new goal for the newspaper: to surpass 10 million subscribers by 2025.

Contact reporter Ren Qiuyu (qiuyuren@caixin.com)

- 1Cover Story: China Carves Out a Narrow Path for Offshore Asset Tokenization

- 2Drownings Shake Chinese Enthusiasm for Travel to Russia

- 3China Business Uncovered Podcast: A $15 Billion Bitcoin Seizure and the Fall of a Cybercrime Kingpin

- 4Over Half of China’s Provinces Cut Revenue Targets

- 5In Depth: Inside the U.K.’s China-Linked Shell Company Factory

- 1Power To The People: Pintec Serves A Booming Consumer Class

- 2Largest hotel group in Europe accepts UnionPay

- 3UnionPay mobile QuickPass debuts in Hong Kong

- 4UnionPay International launches premium catering privilege U Dining Collection

- 5UnionPay International’s U Plan has covered over 1600 stores overseas