Shang Zhou: What the World Can Learn From Italy’s Covid-19 Debacle

|

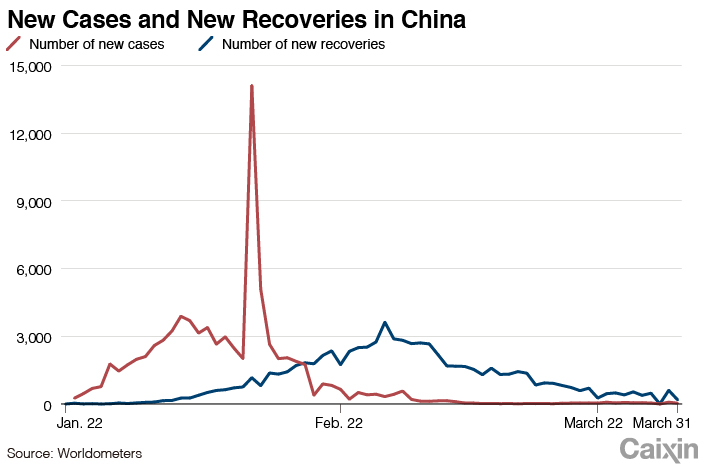

The global picture of the Covid-19 outbreak looked promising Feb. 19 as China’s desperate fight against the disease since January showed signs of progress. On that day, new infections inside China steadied on a downward track, and local authorities started easing restrictions to clear the way for business to resume.

Elsewhere in the world, everything seemed to be under control. Two patients were identified in Iran Feb. 19 while worse-hit South Korea confirmed 58 cases. In Europe, most countries had fewer than 10 confirmed cases. Germany reported the most with 16, but every case was traceable. France had 14 cases by then, and the U.S., 15.

On Feb. 19 the world was quite confident that the new coronavirus outbreak was approaching an end.

What happened next surprised most people as the virus suddenly and quickly spread to every corner of the globe, ravaging more than 880,000 of the world’s population. The battle against the highly infectious virus turned even more desperate than in China.

|

Breaking the calm

Europe first reported Covid-19 cases Jan. 24 in France involving three people who traveled from China. After that, sporadic cases were confirmed in Finland, Sweden, Britain and Italy. As of Feb. 19, a total of 19 cases with travel history to China were recorded. The first local transmission was confirmed in Germany with a cluster of 15 infections.

Altogether, Europe recorded a total of 44 Covid-19 cases by Feb. 19, with only one death of an 80-year-old Chinese traveler in France. Transmission could be clearly tracked for all cases.

At that time, the Covid-19 outbreak still seemed to be too far away for most Europeans to worry about, although local airlines suspended flights to China and traveler screening was toughened at airports.

But the calm broke with a sudden flare-up of cases in Lombardy, a region in northern Italy with 10 million people that includes Italy’s financial capital Milan.

Lombardy was not where the first infections were found in Italy, but it soon became the epicenter of the country’s outbreak.

According to a paper published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) by researchers at the University of Milan, a man in his 30s was confirmed with Covid-19 in Lombardy Feb. 20, setting off the explosive growth of cases. Following the first case, 36 more were confirmed within 24 hours.

None of the new cases in Lombardy had clear links with previously confirmed cases in other parts of Italy, an ominous sign of wider spread of the disease.

The caseload in Lombardy started to surge — surpassing 1,000 by March 2 and 10,000 by March 14. As of March 29, total infections in the region topped 41,007 while case count in Italy reached 97,689.

The fatalities also rose at an astonishing pace. On Feb. 21, Lombardy reported a Covid-19 death in the small town of Vò, the first mortality caused by the disease in Italy. As of March 29, the nation’s death toll reached 10,779, including 6,360 in Lombardy.

With less than 20% of Italy’s population, Lombardy accounts for 40% of the country’s infections and more than half of deaths. It also became the starting point for the journey of the virus across the continent.

The outbreak in Lombardy in late February set off the rapid spread of the virus in Europe. As the chart shows, 41 European countries reported cases imported from Italy, 30 of which had their first case from Italy.

|

The dreadful scene in Lombardy reminds us of Wuhan, the epicenter in China where the virus first emerged. With a similar number of infections, the fatalities in Lombardy have far exceeded those in Wuhan. But unlike Wuhan where early details and statistics remained obscure, the outbreak in Lombardy has been closely tracked with detailed data and records, allowing us to figure out what went wrong in Italy’s combat with the virus.

Out of control

The unknown origin of the first cases in Lombardy posed a huge challenge to the region’s disease control as it was hard to trace where the virus came from and who might have been infected.

But there must be other reasons behind the virus’s freewheeling spread in Italy. The New York Times in a March 21 report blamed Italian authorities for a reluctant and belated response that missed an opportunity to control the virus.

Earlier reaction and stricter enforcement would undoubtedly have made the situation much better in Italy. But before pointing figures at the Italian government, let’s take a closer look at what happened.

Jan. 31, the day Italy confirmed its first two cases, the government set up a special committee overseeing disease control and suspended all flights linking with China.

Feb. 22, two days after the cluster in Lombardy emerged, Italy quarantined more than 50,000 people by placing towns in Lombardy and Veneto on lockdown.

March 1, as the national caseload topped 1,600, Italy rated all regions in the country based on contagion risks and placed quarantine measures in regions with higher risks.

March 4, all schools were closed as nationwide cases surpassed 3,000.

March 7, the government toughened lockdown measures in Lombardy and Veneto.

March 17, Italy allocated 25 billion euros to fund the combat against Covid-19.

March 19, troops were dispatched to Bergamo to support disease control.

March 21, as the country’s total caseload reached 52,578, the government ordered a nationwide lockdown, suspending all nonessential businesses.

The outcome has proved that the government’s moves failed as they always lagged behind the virus’s lethal trajectory. But what exactly went wrong?

|

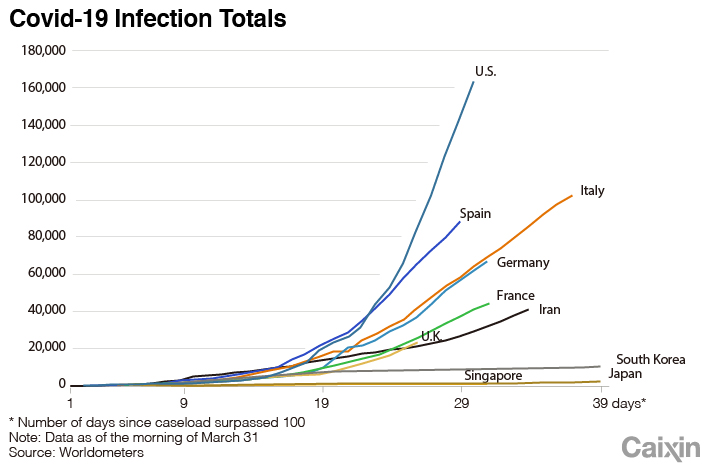

To answer this question, we need to take a look beyond Italy at the rest of the world. A comparison of the outbreak’s curve in different countries shows that Singapore and Japan effectively contained the disease without an explosive growth of infections. South Korea, which suffered a surge of cases around the same time as Italy, also did well by flattening the curve within a month.

But in other European countries and the U.S., the curves are very similar to Italy’s, lagging only a little behind.

Clearly, the failure in containing Covid-19 is not unique to Italy. Instead, it is repeating in other European countries and the U.S. The differences in disease control strategies between these countries and the three better-performing Asian countries could explain the reason.

Europe and the U.S. have followed a similar path in the outbreak by responding with piecemeal efforts and with hesitation to interrupt normal life. The three Asian countries took more aggressive measures to stop the virus. They all adopted broader testing and more-stringent quarantine measures, which are the key to their success in containing the outbreak.

Research by scientists at the University of Padua may explain why the European and American approaches are not enough to control Covid-19. According to The Guardian, scientists conducted virus tests for all of the 3,300 residents in Vò two weeks after the first case was confirmed there and the town was locked down. Ninety of the tests, or 3% of the population, returned positive, although most people showed no symptoms by then.

A second test of residents several days later found no new infections, and six people who previously tested positive returned negative.

The research, although small in scale and not yet completed, indicates that many Covid-19 patients have a long incubation period or are even asymptomatic. If those infected could be identified through massive testing and placed under strict quarantine, the disease could be effectively controlled.

However, in Europe and the U.S., people can get a virus test only when they either show symptoms or had close contact with someone infected. The strict testing standard leaves many asymptomatic patients as hidden sources of infection. In South Korea, about 3,692 out of every 1 million people were tested, while the figure in Italy was only 826.

Lax quarantine measures also undermine disease control efforts in Europe and the U.S. Simply asking suspected patients to stay in self-isolation without strict enforcement doesn’t ensure that everyone follows the rules.

In Asia, more-stringent quarantine measures were applied. For instance, in Singapore, the government used remote surveillance and random inspection to make sure people who should stay in isolation followed the rules.

Using proactive testing to find patients and effective quarantines to isolate those infected are the key reasons the Asian countries were more successful in fighting the virus than Europe and the U.S.

The European and American approach may be effective in dealing with less-infectious diseases such as SARS and MERS, but the unique characteristics of Covid-19 made those measures inadequate.

A comparison of different strategies offers valuable lessons for countries battling the disease. The experiences from Asia could be helpful to other countries. For instance, for those with moderate growth of new cases, the experiences of Singapore and Japan would be useful for preventing a surge of cases. For those entering rapid growth, adopting South Korea’s measures could help contain the surge. And for those suffering explosive growth, lessons can be learned from China’s early battle.

Why is the virus more lethal in Italy?

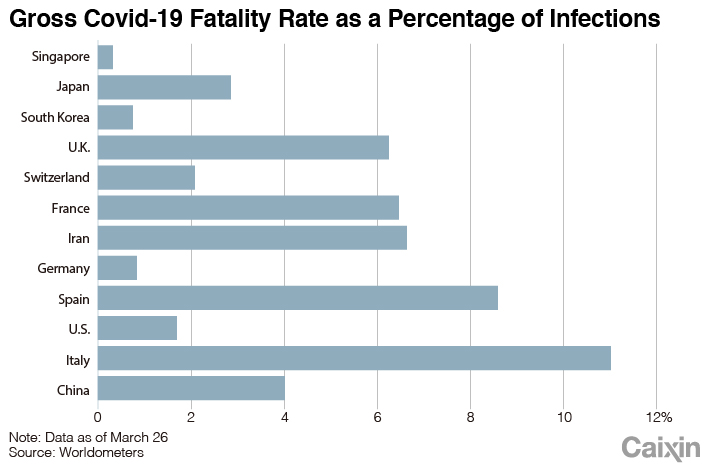

Covid-19 has caused a strikingly high fatality rate in Italy at almost 11% ― 32 times the rate in Singapore. As of March 29, the disease has claimed 10,779 lives in Italy.

|

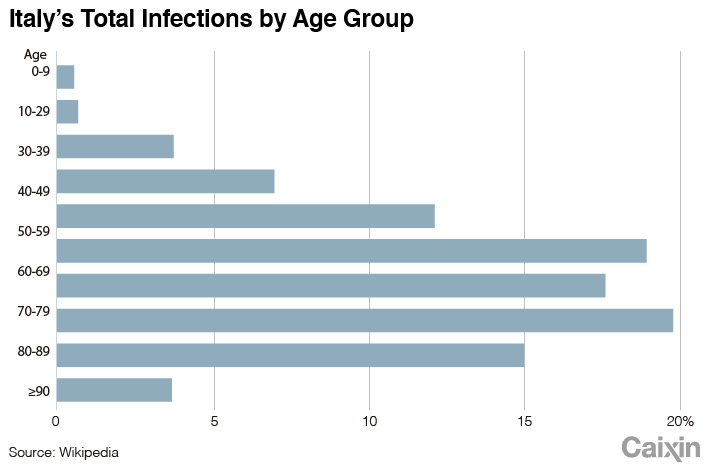

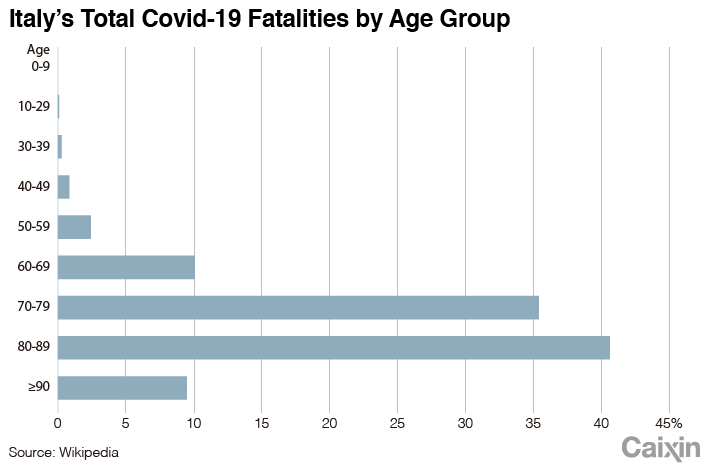

Italy’s elderly are the major victims of the virus. People older than 60 account for 55.7% of Italy’s Covid-19 patients, compared with 20% in South Korea and 15% in Germany.

|

The elderly are much more vulnerable to the disease. Among Italy’s Covid-19 death cases, 95.8% are people older than 60, statistics show.

The high infection rate among older people partly reflects Italy’s aging population. But Germany also has older demographics, so why does it have fewer patients among the elderly?

|

Scholars at Oxford University addressed that question in a preprint paper published on MedRxiv. The article observed that Italy’s tradition of larger families often involving several generations living together and more frequent family gatherings expose the elderly to more infection risks.

Another reason for the high fatality rate is inadequate medical resources. Italy has around 7,000 beds in intensive care units (ICUs), or 13 beds for every 100,000 people. That compares with 28,000 ICU beds in Germany, or 29 for every 100,000 people.

In Lombardy, there were 720 ICU beds with 85% of them occupied by patients with other diseases Feb. 20 when the outbreak started, according to a paper published by JAMA in March.

Although hospitals in the region tried to reserve more beds for Covid-19 patients, the institutions were filled by March 8 and had to transfer patients to other areas. About 16% of Covid-19 patients in Lombardy turned to critical condition, according to the paper.

But as the outbreak worsened outside Lombardy, medical facilities across the country were overwhelmed. Since March 24, Italy started sending some Covid-19 patients to Germany for treatment.

Who’s Patient Zero?

It is still unclear who was the patient zero that ignited the outbreak in Lombardy. According to Italian media reports, the first confirmed patient in Lombardy was a 38-year-old man who started feeling ill Feb. 14. The man made several visits to doctors before he was confirmed with Covid-19 Feb. 20. A number of people who had contact with him, including his wife and several medical workers, were later confirmed with the infection.

But where that patient contracted the virus remains a question as he had no contact with the previous three patients confirmed in the country. Doctors initially believed the patient was infected by a colleague who returned from a business trip in China in late January. However, that man tested negative.

Researchers tried to trace the transmission path of Italy’s outbreak by comparing the virus’s gene sequence. A virologist at the Charité University Hospital in Berlin Feb. 28 found that the virus from a German patient infected in Italy was very similar to that of a virus found in a patient in Munich about a month earlier — both shared three mutations not seen in early sequences from China. The finding indicates that the outbreak in Italy is likely to be linked to a previous cluster of infection in Bavaria, although German authorities said that outbreak was contained.

A separate study by scientists in Milan also suggested that Italy’s coronavirus outbreak might have come to the country via Germany instead of directly from China, based on the sequence of the viruses found in the two countries.

But some researchers also argued that the similarity in gene sequence is not sufficient to make a link between Italy’s contagion and Munich. Therefore, the hunt for the origin of the contagion in Italy continues.

Tracing patient zero is not to find someone to blame but to help us better understand the transmission of the virus. The Covid-19 pandemic has proved that the virus doesn’t respect boundaries, and it will require the united efforts of the whole world to defeat the disease.

I am confident that humanity will be the winner in its war with this virus. The only question is the time and cost we pay for the victory.

Shang Zhou is an immunologist and a blogger. The original Chinese version of this article was published on the science-focused website Zhishifenzi.com

Translated by Han Wei (weihan@caixin.com)

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR