Cover Story: How Bill Gates Sees China Expanding Its Role in Global Health

Bill Gates transformed his career from technology to philanthropy with his move a dozen years ago from running Microsoft Corp. to working with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. But the billionaire’s belief in innovation and optimization remained unchanged from the business world to charitable missions.

Started by Gates and wife Melinda in 2000, the Gates Foundation has become the world’s largest private foundation with $46.8 billion of assets. It is playing an increasingly prominent role in global health. In the 2018-19 fiscal year, the foundation donated $531 million to the World Health Organization, making it the United Nations group’s second-largest supporter behind the United States.

The Gates couple and billionaire Warren Buffett are the foundation’s only trustees, providing the foundation’s funding.

The group backs a large number of organizations and partners working in a vast range of global health initiatives, including the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, which are leading the development of vaccines for the Covid-19 pandemic.

In January, the Gates Foundation provided $5 million of emergency funding to China as the first global organization to do so. Since then, the foundation has made commitments of more than $350 million to fight against the global pandemic and protect vulnerable populations.

Since he stepped down from Microsoft management, Gates has shifted his focus to philanthropic works and become deeply involved in the foundation’s operations. He describes what he does as “optimization” to ensure that limited resources can help as many people as possible

“We still believe that everyone deserves an equal chance to live a healthy and productive life and that innovation is critical to making that happen,” the 64-year-old business magnate told Caixin.

The Gates Foundation’s network covers 138 countries and regions, making about 1,700 donations every year to research institutions, companies, government organizations, nonprofit entities, U.N. agencies and others, focusing on public health, education equity, environmental protection, gender equality and agricultural innovation.

|

| Bill Gates and wife Melinda |

The foundation has been active in China since 2007, focusing on HIV/AIDS prevention, tuberculosis (TB) treatment and tobacco control. As a growing power, China has contributed to global development, and its increasing global engagement has benefited people in other countries, Gates said.

According to Li Yinuo, China director of the Gates Foundation, the organization is seeking more cooperation with China to bring the country’s advanced agricultural technology, malaria control solutions and more China-developed medicine and medical equipment to the world while helping China to close the gap between its medical system and international standards.

In a recent email interview with Caixin, Gates explained how the foundation sets priorities and deals with unexpected results. He assessed the foundation’s response to the Covid-19 outbreak and his engagement in the foundation’s operations. Although five years ago he predicted that the next big global crisis would most likely be a pandemic and started investing in preparedness, he acknowledged that the world wasn’t ready.

Here’s a transcript of the interview:

Philanthropic strategy

Caixin: The Gates Foundation, jointly with the governments of Norway and India, the Wellcome Trust, and the World Economic Forum, launched CEPI in 2017 aiming to accelerate the response to epidemics and quicken the creation of vaccines once an outbreak occurs. Do you think what CEPI and Gavi are doing now for the Covid-19 pandemic meets your expectations? If you could have done it all over again, what else would you push the Foundation and its main grantees to do in responding to the pandemic?

Bill Gates: One of the things that has impressed me in the Covid-19 response is the way governments, business, and global organizations are working together to solve problems quickly. CEPI and Gavi are an important part of this international collaboration, and they are doing an excellent job.

CEPI has been critical in the quest to find a Covid-19 vaccine. The very fact that an organization dedicated to developing vaccines for epidemic diseases was ready to step in right away is new in the history of global health. And it’s encouraging to see governments stepping up in recent months to donate to CEPI. I’m optimistic we will have a vaccine in the first half of next year, which is phenomenal and shows what a big game changer CEPI can be. It’s important that we continue to fund the organization even after this pandemic ends so it can continue bringing successful vaccine candidates forward.

Gavi was created 20 years ago precisely to make sure vaccines get to children in developing countries. Once a Covid-19 vaccine is ready, Gavi will be a key partner in delivering it to the people who need it. At the recent Gavi replenishment meeting, donors actually pledged more than the organization asked for. This means that it will be able to continue helping countries run routine immunization programs in safe ways while it also prepares to distribute the eventual Covid-19 vaccine.

How has the foundation set its donation priorities over the past 20 years and what is its approach to evaluate and review projects? Has the foundation made significant adjustments to its strategies?

Our overall goal of equity is the same. We still believe that everyone deserves an equal chance to live a healthy and productive life and that innovation is critical to making that happen.

A lot has changed over the last two decades, though, even if our high-level mission is the same. We have adjusted many of our strategies based on lessons learned from our work. We used to focus narrowly on health; now we also focus on other areas of development like agriculture and financial services. We began by looking at health in terms of individual diseases; now we see it more as an interconnected set of issues. We began with a focus on discovering and developing new products; while that is still a key aspect of our work, we concentrate just as much on the challenges of delivering those products to the people who need them. As digital technology has taken hold in the past decade, we have increasingly factored these advances into our work. We have invested in data to understand how gender inequality blocks progress and the role we can play to help women and girls gain power and influence.

Are there projects that received the foundation’s funding but didn’t deliver expected results? If so, which one impressed you most and why?

Over the years, we’ve had a number of projects that didn’t go as expected but still delivered important results. Our work with partners on polio, for example, has brought the world extremely close to eradication, but it has taken longer than I thought it would to finish the job.

When you get down to a very few cases — there have been about 100 cases per year in the past couple of years — the work gets increasingly difficult; the strategies that worked to reduce the disease by 99.9% don’t work for the last 1%. However, we have learned many lessons that will help us do better, not just on polio eradication but also on many other global health challenges, including Covid-19. We have learned how to identify and monitor the spread of a virus with phenomenal precision. We have learned how to organize public health campaigns that reach virtually every single child in large and remote areas. We have learned how to build trust with communities experiencing violent conflict. When our partners encounter a problem, they innovate to find solutions, and many of those solutions have applications beyond polio.

We will eradicate polio. It will have taken much longer than we hoped, but the struggle has made the global health community better at all of its work.

The foundation has become a uniquely important player in the global health system and outperformed many other private organizations in similar areas with its clear goal-setting and achievements. What are the experiences and lessons you can share with other foundations or philanthropists that also want to contribute to global health?

The global health ecosystem is complex, and we all have distinct roles to play. What matters is not how much money an organization has but how their resources align with their strategies. That is why we work together with businesses, governments, and community organizations, among others, because each partner brings important skills and perspectives.

Still, we are learning lessons every day, and we share them whenever they may be relevant to our partners. Take the example of using data and evidence to design strategies and track results. It’s not just our foundation that does that, it’s everyone. We are just as eager to learn from our partners’ experiences. Studying what others do well and adapting those lessons to your unique context is a good way to get better.

Editor’s note: Optimization and innovation are the key words Gates emphasized for the Foundation’s strategy. The goal is “using limited resources to help as many people as possible,” he said. Under the principle set by the three trustees, the foundation is obliged to spend at least $4 billion every year for charities. About 60% of the funds go to support global health projects.

One of the main focuses of the foundation is to promote the coverage of childhood vaccines. “Saving children’s lives is the best deal in philanthropy,” the Gates couple said in their 2017 Annual Letter. “And if you want to know the best deal within the deal—it’s vaccines.” That led to the creation of Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, in 1999 with an initial investment of $750 million from the foundation.

According to the letter, more than 122 million children under age 5 have been saved since 1990. And vaccines are the biggest reason for the drop in childhood deaths.

But not every project runs as expected. The initiative to eliminate polio has gone back and forth. Since 1988, the number of global cases of the disease has been reduced by 99% after large-scale vaccinations. In 2015, the WHO announced that polio is no longer a public health threat. But sporadic outbreaks have never been fully eliminated. In 2018, 33 polio cases were reported, all from Pakistan and Afghanistan. Gates described the remaining work against the disease as a game of whack-a-mole.

“Some of the projects we fund will fail,” the Gates couple wrote on the website of the foundation. “We not only accept that, we expect it—because we think an essential role of philanthropy is to make bets on promising solutions that governments and businesses can’t afford to make. As we learn which bets pay off, we have to adjust our strategies and share the results so everyone can benefit.”

Gates said he has been passionate about tasks to eliminate polio, address climate change and improve global health. To make effective changes, it is important to bolster cooperation among professionals from academic, government and many other fields. “You won’t succeed unless you can reach a broader audience and reshape people’s mindset,” he said.

But in the face of rising protectionism and inward-looking strategies among countries, forging global cooperation to deal with public health challenges is becoming increasingly challenging, he said.

Tech mogul-turned philanthropist

As the founder of a private foundation, you’re unique because you play a key role in the organization and administer a lot of projects in person, while most other foundations are run by professionals instead of the founder. Why are you able and willing to do this?

Almost 25 years ago, Melinda and I read an article that said 500,000 children were dying every year from a disease we’d never heard of called rotavirus, almost all of whom lived in low-income countries. Children in high-income countries got rotavirus, it said, but didn’t die from it. We were blown away. We kept asking ourselves how so many children could die from a disease that was easily treated. And how had this brutal inequity lasted so long without our even knowing about it? So we committed to learning about and eventually investing in global health even while I was still at Microsoft. We thought if our money and our ideas could help save and improve lives, then we had a responsibility to contribute.

As our work evolved, I got increasingly passionate about it. I believed we had an opportunity to do something important, and I wanted to spend more time on the work.

So, in 2007, I stepped down from my full-time role at Microsoft and started working full time with the foundation. In many ways, my careers in technology and global health have been similar. Both have been focused on innovating to solve the world’s toughest challenges and improve people’s lives.

When the foundation was established, was there a picture in your mind about how the world would be in 20 years? What changes did you expect to bring at that time? Is there a gap between your expectation and the reality now?

When we started the foundation 20 years ago, we hoped that investments in vaccines and other medical supplies — and ways to deliver them — would help more kids survive and grow up healthy. And while we have a long way to go in the fight against extreme poverty and disease, the data do show things have gotten better.

Since 2000, the number of children who die before the age of 5 has fallen by nearly half, even as the population has gone up by approximately 25%. Many of our foundation’s partners have been extremely successful. Gavi has immunized more than 760 million children since 2000. The Global Fund, which helps countries tackle HIV, tuberculosis and malaria, has saved more than 30 million lives since 2002. Unfortunately, this progress is likely to slow down temporarily because of Covid-19.

Back in 2000, when we started the foundation, I didn’t expect that our work would intersect with the worst global health crisis in a century. We started our foundation before SARS, before MERS, before Ebola. And so, I did not see the looming threat of pandemic disease, and it wasn’t a major part of our strategy. We started talking about the issue, and our foundation started investing in preparedness about five years ago, but the world wasn’t prepared enough to prevent a pandemic.

|

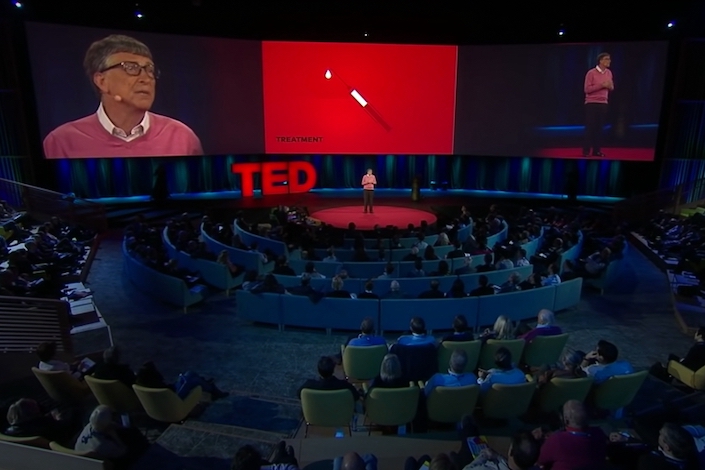

| Bill Gates warned risks from a pandemic in a TED Talk 2015 |

Editor’s note: In a 2015 TED Talk, Gates prophetically warned that the next big disaster to strike humanity would be due to microbes, not a nuclear war. He said that the world would be underprepared for such a viral disaster. Unfortunately, he was proved right by the Covid-19 pandemic.

As a tech superstar, the Microsoft co-founder is known for many anecdotes illustrating his relentless eagerness for learning and working as well as his hyper-competitive personality. The skills he learned at Microsoft including deep understanding of technology and organizational operation has helped him in his philanthropic career, Gates said in a 2016 interview with Caixin.

But years of involvement in philanthropic works focusing on disease control and poverty relief have also transformed him. “I have mellowed. Thank god,” Gates said in Netflix’s three-episode documentary series last year, “Inside Bill’s Brain.”

At the early days of the Gates couple’s philanthropic efforts, they mainly focused on using technology tools to improve fair education, such as donating computers and education resources to African countries. Since the late ‘90s, they started shifting to efforts to control disease and improve global health, especially for children.

Building bridges

The foundation has been in China since 2007. How has its knowledge about China and about what it can achieve together with China evolved?

When we started our work in China, it was to help the country address major domestic public health challenges: HIV prevention, tobacco control, and tuberculosis control.

Last year, I visited China to celebrate the 10th anniversary of the TB prevention and control program with our partner, the National Health Commission. The scale and scope of the effort have been impressive, with breakthroughs in diagnostics, treatment, and backend solutions like insurance reimbursement and information management benefitting 90 million people.

China has become an increasingly important partner in helping the world achieve global health and development goals. That’s a clear trend over the past 20 years: China has transitioned from being a recipient of health and development support to being a donor of it. The country is responsible for providing all sorts of antimalarial products for people in sub-Saharan Africa, like bed nets, and helped develop the latest Japanese encephalitis vaccine, which is now in 12 countries and has protected more than 400 million children.

In the face of the Covid-19 pandemic, it is great to see China continue taking a leading role in global cooperation, with pledges of support for the WHO and Gavi as well as $2 billion to help affected developing countries with Covid-19 response.

What role does philanthropy play? What’s your observation of China’s philanthropy development?

As a percentage of the economy, philanthropy in China is still fairly modest, at less than 0.2% of GDP. But China’s remarkable growth has created new wealth for a generation of entrepreneurs — wealth that can benefit people in China and around the world.

At its best, philanthropy takes risks that governments can’t and corporations won’t. Business doesn’t generally invest in products for people who can’t afford to pay for them. Government can provide a safety net by offering services the market doesn’t. But it’s hard for any government to justify big investments in research that may only benefit people in far-off countries, and some countries simply don’t have enough money to invest in R&D. These are the kinds of gaps China’s new philanthropists can fill.

After all, the Covid-19 pandemic is showing us that the world’s biggest problems can’t be solved by any single entity alone. They require cooperation from governments, businesses and nonprofits. Gavi is a good example. It not only helps immunize millions of children against preventable diseases; it has also pledged that once a Covid-19 vaccine is ready, it will help deliver it to low-income countries. When Gavi needed more funding this year, the Chinese government made a contribution. But so did a collection of Chinese institutional donors, technology firms and vaccine manufacturers.

Investments in multilateral health institutions like Gavi are smart bets, and by contributing to them, China and its philanthropists won’t only accelerate the end of this pandemic; they’ll help create a better world after.

Editor’s note: The Gates Foundation opened its first overseas representative office in Beijing in 2007, but its engagement in China started much earlier. Between 2002 and 2007, Gavi partnered with the Chinese government to launch a $76 million project to develop and promote hepatitis B vaccine in rural China. Over the years, the foundation has been involved in many projects in China including fighting against tuberculosis, improving childhood nutrition, preventing HIV and tobacco control. The foundation’s work approach in China has also evolved from direct donation to more diverse patterns and partnerships.

The foundation also helped link China and other countries in development cooperation as China evolved from charity recipient to contributor. In 2013, a Japanese encephalitis (JE) vaccine developed by China National Biotec Group was prequalified by WHO, and later

selected by Gavi for its vaccination program for developing countries. Between 2014 and 2018, a total of 30 million China-made JE vaccine doses were donated to Laos, Nepal and Cambodia through Gavi. To date, more than 400 million children from 12 countries have benefited from the vaccine, and millions of lives are saved.

In 2015, China for the first time donated $5 million to Gavi to support its global childhood vaccination initiative after years of support from the organization helped China bring hepatitis B under control. Last month, the Chinese government offered additional $20 million to Gavi during the Global Vaccine Summit and pledged to encourage Chinese research institutions and vaccine manufacturers to strengthen collaboration with Gavi.

Contact reporter Han Wei (weihan@caixin.com) and editor Bob Simison (bobsimison@caixin.com)

Correction: The previous version of this story mistakenly stated that the foundation's initiative to control TB has gone back and forth. It should be the initiative to eliminate polio.

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR