Virtual Reality Loses Luster But Stays in the Game

(Beijing) — Two days before Christmas, a maker of augmented-reality goggles suddenly broke its office lease in an upscale Beijing building, forcing staffers to box up their belongings and move out.

Beijing Alto Tech Co. Ltd.’s unexpected downsizing was tied to a capital crunch more serious than anything the 3-year-old company had ever experienced, company founder Ye Chenguang told Caixin.

Alto's experience is not unique among Chinese companies in the virtual reality (VR) sector and its cousin, augmented reality (AR). The industry whose players include computer-game makers, manufacturers of VR goggles and app developers is now cooling off following an investment splurge driven by high expectations for consumer demand — a demand that has yet to materialize.

|

Chinese entrepreneurs and investors started smelling profit potential about three years ago after Facebook bought the VR startup Oculus for $2 billion. Startups and investors later piled in after global tech giants Sony Corp., Google and HTC Corp. started developing VR hardware.

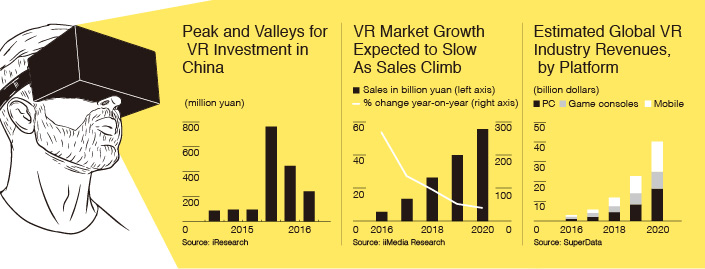

VR-targeted investment grew rapidly. For example, investment in Chinese VR companies surged to 761 million yuan ($110 million) in the fourth quarter of 2015, up 720% from the third-quarter total. Some of China's largest electronics companies such as Huawei Technologies Co. Ltd., Xiaomi Inc. and LeEco also got into the game.

The industry was still rocketing skyward when the government's securities regulator decided trouble was brewing for major listed companies whose core businesses had nothing to do with VR.

To rein in fundraising tied to potential speculation, the China Securities Regulatory Commission (CSRC) in early 2016 ordered listed firms to stop selling stock specifically designed to raise capital for investments related to VR as well as internet finance, video games, films and television. The rule thus cut off an important funding channel for the emerging VR industry.

Moreover, startup VR companies with private funding sources, as well as the listed electronics giants targeted by CSRC, have been affected by a shortage of quality content, a lack of consumer-pleasing apps, and technological limitations. These obstacles have thus limited the VR industry's nationwide user base and, ultimately, revenues.

Investors responded to the industry's woes by stepping back, which, in turn, forced companies such as Alto to scale down operations.

Down But Not Out

Looking ahead, industry insiders say the content production and delivery through apps, not goggles and other hardware, will be the most competitive arena for VR companies in the future.

Already, Xiaomi VR app downloads exceed the company's VR goggle sales by as much as 50%, the general manager of the company’s VR department Tang Mu told Caixin. That's because many app users access VR content through hardware made by other companies.

To really spark consumer demand, according to industry watchers, China's VR industry will need a phenomenally popular app. So far, though, no such app has been developed.

Complicating the industry’s development is the Chinese government prohibition on the globally popular Pokemon Go app, which helped make AR familiar to millions of the game’s players worldwide. The State Administration of Press, Publication, Radio, Film and Television, which oversees the computer game industry, said in January that the popular app will not be allowed for the time being because it poses “a relatively large risk to society.”

In addition to gaming, many firms are working to produce virtualized video content. But the video field is being approached cautiously, in part because VR video production costs are high.

China’s leading online video producer and platform, iQiyi, plans to release only 10 shows viewable with VR technology in 2017, company Vice President Duan Youqiao told Caixin. And each show will be less than 20 minutes long.

iQiyi's commitment is influenced by the fact that a VR video costs several times more to produce than a standard video, Duan said.

Neither do VR games come cheap. A simple game can cost tens of millions of yuan, Li Wen, co-founder of the Beijing-based VR startup Snooow, told Caixin. Snooow makes ocean-related video and games for educational purposes.

High costs against the backdrop of regulatory restrictions and content limitations have thus cooled investor interest. Li said a VR game developer these days is having trouble raising even 1 million yuan. As a result, he said, nascent game companies have found it “extremely difficult, instead of relatively difficult," to make ends meet, Li said.

Big game names in China have thus chosen to keep their VR staffs small. The nation's second-largest game developer, NetEase, launched its first VR game in November after it was crafted by a team with only 20 members. And Xiaomi’s VR department has only 50 people.

The modern history of the consumer electronics sector has been cited by some futurists who argue that VR is the next big thing.

But industry players such as Yao Zhen, a veteran game developer, thinks VR users are merely video gamers. He also doubts the technology will be able to duplicate the success of smartphones, which appeal to old and young, rich and poor.

Duan of iQiyi likens VR's current status to the highest part of a pyramid, arguing the sector shares a consumer market with movie theaters. Television and video, meanwhile, can be compared to the rest of the pyramid, owing to their much larger user base.

Duan uses this analogy to explain that VR use, like moviegoing, will probably never equal TV as an everyday form of entertainment.

“Some say that in the future, everyone in China will hold VR gear in their hands," he said. "That's nonsense, just as it's impossible for people to go to the theater every day.”

Underscoring Duan's argument is another disappointing segment of the VR industry: The VR theme store, where customers pay to play virtualized games, ride roller coasters and race cars.

Although China's leading VR theme store operator Leke has a network of more than 2,000 franchised outlets, regular customers are few. The stores have attracted more than 7 million people since 2015, company founder He Wenyi told Caixin, but no more than 6% have visited more than once. And Leke has yet to turn a profit.

Of course, it takes time for any new industry to mature. The U.S.-based technology research firm Gartner Inc. last year predicted another five to 10 years would likely pass before VR reaches the level of "mainstream adoption."

So while companies such as Alto are now struggling to make money, and investors have caught a chill, the VR industry is still very much a reality.

Contact reporter Coco Feng (renkefeng@caixin.com)

- 1Cover Story: China Carves Out a Narrow Path for Offshore Asset Tokenization

- 2Drownings Shake Chinese Enthusiasm for Travel to Russia

- 3Over Half of China’s Provinces Cut Revenue Targets

- 4Li Ka-Shing’s Port Empire Hit by Forced Takeover Amid Panama Legal Dispute

- 5In Depth: China’s Mutual Fund Industry Faces Overhaul After a Banner 2025

- 1Power To The People: Pintec Serves A Booming Consumer Class

- 2Largest hotel group in Europe accepts UnionPay

- 3UnionPay mobile QuickPass debuts in Hong Kong

- 4UnionPay International launches premium catering privilege U Dining Collection

- 5UnionPay International’s U Plan has covered over 1600 stores overseas