Goodbye, Dali: Hip Tourist Spot Turns Into Ghost Town as Sewage Scare Prompts Shutdown

(Dali, Yunnan province) — Once a magnet for tourists, the bustling waterfront of Dali now looks like a ghost town, a little over a month after the local government ordered over 1,000 bars, restaurants and hotels dotting the shores of idyllic Erhai Lake to shut down.

Owners were given 10 days’ notice to cancel bookings and wind down operations after authorities announced on March 31a sweeping review of the waste disposal systems of businesses around China’s second-largest highland lake. It is not clear how long the review will last, and the government has not announced any compensation for losses accrued.

The drastic move was prompted by a three-month-long algae outbreak on the river in late fall, which reappeared in January and lasted until the end of Lunar New Year at the end of the month.

Authorities have partly blamed these businesses — many of which are operating without a license — for dumping raw sewage, food waste and other garbage into waterways feeding the lake.

But business owners say a freeze on their operations will only turn into a costly temporary fix because the real problem is the area’s lack of a sewage treatment facility and a garbage collection system.

“Why are the businesses suddenly the culprits for a long-standing problem?” asked Tian Jing, a hotel owner from neighboring Guangdong province who invested 3 million yuan ($436,000) in Dali after the local government introduced a slew of measures to attract investors in recent years. “Why has no one been held accountable for taking so long to tackle the pollution problem in Erhai?”

The Dali government has pledged 3 billion yuan to build a pipeline network and a sewage treatment facility through a public-private partnership by 2020. But until then, cleaning crews on boats will have to fish out tons of algae bloom that are choking the lake.

|

Two abandoned fish ponds contain some of the sewage, algae and water hyacinth that flowed into Erhai Lake from the Shuangyuan stream in Yinqiao town of, Dali, Yunnan province, on April 20. Photo: Chen Liang/Caixin |

The number of visitors drawn to this oasis seeking an eco-bohemian lifestyle has nearly quadrupled over the past decade, according to official figures. There were over 40 million visits last year alone.

This influx has fueled a construction boom. In Shuanglang, a 1,000-year-old fishing village, the number of small restaurants and motels exploded from a handful to nearly 580 establishments in the past few years. But nearly 90% were operating without a license, Tian said.

“But who allowed the tourism industry to grow so recklessly in the first place?” she asked.

|

Sewage pipes are laid in Gusheng village, Yunnan province, on April 20 in an effort to reduce the pollution of Erhai Lake. Photo: Chen Liang/Caixin |

“We have no way out but to fight a make-or-break battle when it comes to tackling pollution in Erhai Lake,” Dali Party Secretary Chen Jian said.

The Dali government has also appropriated farmland and shut down cattle ranches near the lake to prevent fertilizer runoff from poisoning its waters. Families have been ordered to seal their wells due to fears that they may deplete groundwater stocks, which in turn would affect water levels in the lake. Fishing has also been banned since January.

|

A sewage treatment plant is under construction in Dali, Yunnan province, on April 20. Photo: Chen Liang/Caixin |

The local government said it will allow businesses that have the necessary sanitation and hygiene certifications and a slew of other documents needed to function legally to reopen as soon as the “reviews on the establishment are completed.” But they haven’t offered any compensation for losses due to the curb.

Local media are calling the government’s move, which has paralyzed the region’s tourism industry, as a form of “shock therapy.”

Choked by Algae

The sudden crackdown by the government has another aim: to reduce the number of permanent residents living on the shores of Erhai Lake and around areas designated as conservation zones.

A local government plan viewed by Caixin said it is best to maintain the population around the lake at 200,000 to 500,000 to control pollution.

But the number of permanent residents running cafes, bars, guesthouses and karaoke clubs on the lakefront has ballooned to 860,000 people, overwhelming the area’s already fragile sewage system.

|

One worker said that his small team of about 10 people usually collects 12 boatloads, or 100 cubic meters, of waste every day, and the algae breakouts were getting worse.

The lake was choked by blue algae for over three months last year, up from just 15 days in 2014 and 45 days in 2015, according to government data.

A local government document viewed by Caixin showed that workers had collected nearly 23,000 tons of algae from the lake between November and March during the latest outbreak.

Officials in Dali fear that Erhai Lake will face the same fate as the province’s largest lake, Dianchi, which has been polluted by agricultural runoff and the unregulated rise of tourism.

Locals still call Dianchi Lake in the provincial capital of Kunming “the mother lake.” Although the government has spent nearly 50 billion yuan to clean it up over the past two decades, it remains toxic.

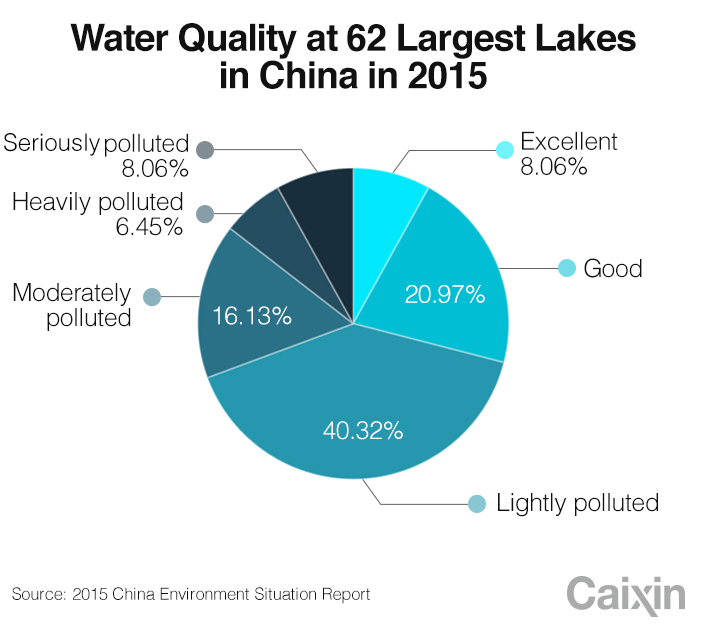

Decades of lax environmental laws and negligible punishments for violators has meant that many of China’s large water bodies are now polluted. Forty-four of the 62 large lakes in China under the watch of the Ministry of Environmental Protection are somewhere between lightly and heavily polluted, according to the 2015 China Environment Situation Report, released by the ministry in May 2016.

In the case of Erhai Lake, booming tourism coupled with reclamation of wetlands around the lake for farming has led to the alarming pollution seen in recent years, according to a recent government assessment.

Killing the Cash Cow

Fertilizer runoff from crop and cattle farms around the lake was the source of more than half of the nitrogen- and ammonia-based pollutants in Erhai Lake, according to a 2013 study by the Central China Normal University.

Nearly 90% of the small cattle farms in Dali that have about 40,000 dairy cows lack proper waste-disposal facilities, according to a research by Zhou Jing, a city planner at the China Center for Urban Development. Each cow generates 25 times the waste a human, said Zhou.

Local farmers also grow garlic, which they called their “cash-cow crop.” “We used to earn 150,000 yuan from planting garlic or tobacco on an acre of land every year,” said Li Zhuhou, a farmer from Gusheng village.

But the government is now taking over the land for “organic and water-efficient farming” and has promised to pay farmers 12,000 yuan per acre in compensation every year, according to land-lease document viewed by Caixin.

Asked how his family will cope with this sudden loss of income, Li fell into a long silence before mumbling, “I don’t know.”

Small-business owners who were the backbone of the local tourism boom are facing this same uncertainty.

Contact reporter Li Rongde (rongdeli@caixin.com)

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR