Late Journalist Opened Window Onto World for Emerging China

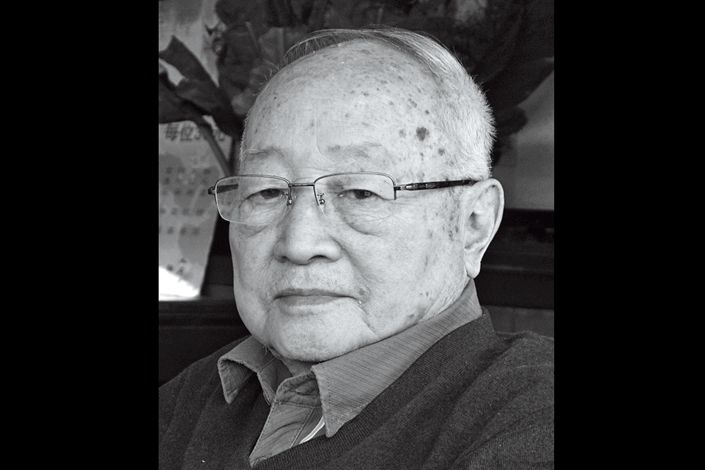

Zhang Yan, the People’s Daily’s first U.S. correspondent and a respected journalist whose career spanned a dramatic half-century of Chinese history, has died at the age of 96.

He witnessed war, the surrender of the Japanese, and Mao’s founding of the People’s Republic — all by age 23. He narrowly missed being caught up in an assassination attempt, was banished to a re-education camp, and later went on to become one of China’s most celebrated reporters as he covered historic events abroad.

Born in Guangdong province in 1922, Zhang spent his formative years under the shadow of the Japanese occupation. In the 1940s, he attended the National Southwestern Associated University, which was the result of a temporary merger between the prestigious Peking, Tsinghua, and Nankai universities, whose staff and students had been driven inland by Japanese forces from their campuses in Tianjin and Beijing to Kunming in remote Yunnan province.

Zhang, a strong advocate of communism as a young man, got his start in journalism at the U.S. Office of War Information outpost in Kunming. His first assignment was the Japanese surrender ceremony in Zhijiang county, Hunan province, on Aug. 21, 1945. Watching representatives of the Japanese military sign the surrender document was the “happiest experience of my life,” after years of war, Zhang later wrote (link in Chinese).

Kunming was also where Zhang developed his first links to the United States, as he recalled to China Daily in 2011, when he began lifelong friendships with a few American soldiers at a bookstore in Kunming.

Birth of the People’s Republic

After the war, Zhang became a reporter at Hong Kong-based periodical China Digest. He was at Tiananmen Square when Mao Zedong declared the founding of the People’s Republic China on Oct. 1, 1949 — a moment Zhang captured on film with his Contax rangefinder.

Zhang made his first trip out of the country in 1952, as part of a Chinese delegation to the Soviet-organized World Congress of People for Peace in Vienna, led by politician and widow of Sun Yat-sen Soong Ching-ling.

He was also asked to follow Chinese premier Zhou Enlai to the first Afro-Asian Conference in Bandung, Indonesia, in 1955 — a pivotal meeting of delegates from newly independent Asian and African states that laid the groundwork for the Non-Aligned Movement.

Zhang planned to leave for Bandung on April 11, 1955, along with a number of other journalists and Premier Zhou himself. But an emergency medical appointment delayed Zhou’s travel plans for a few days, and Zhang’s team was also asked to wait (link in Chinese) before traveling to Indonesia. That twist of fate may have saved the premiere’s life — and Zhang’s as well.

On the afternoon of April 11, a bomb exploded on board the aircraft Kashmir Princess, which they had initially planned to travel on. The plane crashed into the South China Sea, killing 16 of its 19 crew and passengers, including a number of Chinese delegates and an international group of journalists. The explosion was later found to have been an assassination attempt on Zhou.

Fall from favor

The late 1950s and 1960s brought a major change in circumstances for Zhang. He went from hobnobbing with the party elite to being a target of the Anti-Rightist Campaign in 1957. He was expelled from the Communist Party in 1959.

Then, during the Cultural Revolution of the late 1960s and the preceding “Four Cleanups Movement,” Zhang was labeled a “rightist spy” and sent to rural Ningxia for re-education. He faced public criticism, and his home was searched and possessions confiscated.

Zhang was finally rehabilitated in 1979. Later, reflecting on the dramatic changes he lived through, Zhang said that in the 21 years between 1957 and 1979, “it was like a nightmare, where I suddenly somehow changed from man to ghost.” Then, just as suddenly, he “returned to being a normal person, a respected person.”

Window onto the world

The year Zhang emerged from exile, 1979, was also a year of earth-shattering transformation for his country. Deng Xiaoping, the new chairman of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference, had announced major reforms the previous year including decollectivizing farming and allowing private enterprises to operate for the first time since 1949.

Beijing officially established diplomatic relations with the U.S., and the newly rehabilitated Zhang was selected to be the People’s Daily’s first U.S. correspondent.

Zhang’s work opened a window onto the rest of the world for readers in China, which was emerging from decades of isolation. He covered the 1980 landslide victory of presidential candidate Ronald Reagan against Jimmy Carter, explaining the electoral college system to readers and analyzing the mid-campaign deadlock between the candidates in articles like “What Happens if No President is Elected?” (link in Chinese).

Toward the end of his career, Zhang worked at China Reconstructs, a periodical focusing on China’s development, founded by Soong Ching-ling in the 1950s and later renamed China Today. He retired in 1989.

Zhang took a modest view of his role as a witness to history. In a letter to his son in the 1990s, he wrote: “The bumpy road I have travelled is something that many people in China — hundreds of thousands of them — have experienced, some even worse than me.”

Contact reporter Teng Jing Xuan (jingxuanteng@caixin.com)