Questions Persist Over Coronavirus Fatality Rate

|

As China’s coronavirus outbreak continues to sicken tens of thousands of people across the country, public health officials are puzzling over a grim, but elusive, question: just how deadly is it?

Wide local, provincial, and national discrepancies in a statistic called the case fatality rate — the proportion of deaths among confirmed cases — have complicated the response from governments in China and around the world to the fast-escalating outbreak, which as of Wednesday had infected more than 28,000 people globally and killed at least 565.

Closely linked and frequently confused, the case fatality rate is different from what’s known as the mortality rate. The former looks at how many people who catch the disease actually die from it, while the latter counts how many people die from it within a given population.

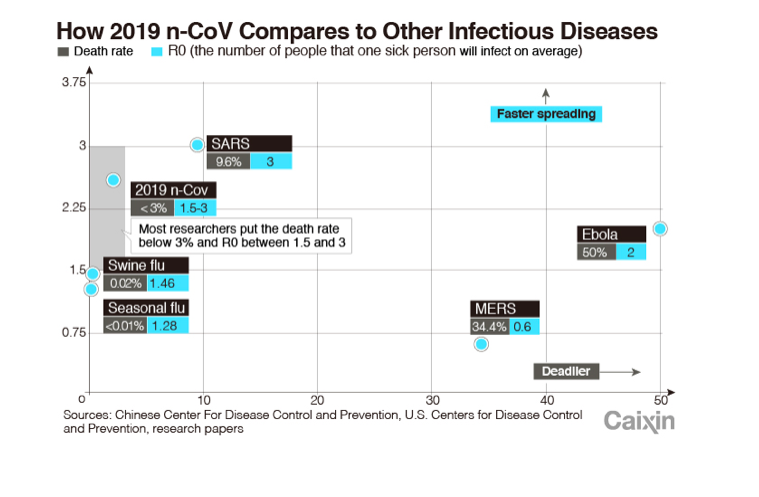

On Tuesday, Jiao Yahui, deputy director of the National Health Commission’s state health administration, said the nationwide case fatality rate for the new coronavirus was 2.1%, meaning around 1 in 50 people diagnosed with the disease in the country so far had died. That compared to a rate of around 10% for SARS.

But a breakdown of that figure revealed significant variations. In Wuhan, the city at the center of the outbreak where nearly three-quarters of China’s coronavirus-related deaths have occurred, Jiao said the case fatality rate was as high as 4.9%. Similarly, when the nationwide rate was calculated excluding data from Hubei, the province where Wuhan is located, the figure fell to just 0.16%.

Jiao attributed the higher figure in Wuhan to the city’s overwhelmed hospitals, saying that at the start of the outbreak patients with severe symptoms rapidly occupied the available beds at three designated hospitals, forcing many to transfer to more than 20 other facilities. That dispersed infected patients more widely around the city and diluted the quality of medical care they received, she said.

Jiao added that Wuhan was setting in motion more robust measures for managing severe coronavirus cases and she believed that “before long, their effects will become apparent and Wuhan’s case fatality rate should gradually come down.”

Large differences in case fatality rates were more likely to reflect underlying biases in currently available data than “true” variations in the virus’ deadliness, experts told Caixin.

“It could be accurate that the (proportion) of deaths in Wuhan is higher because there are capacity shortages and overburdened staff,” said Tom Inglesby, a specialist in infectious diseases and the director of the U.S.-based Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security. “But there is not enough information being shared internationally to be able to assess that.”

|

Ben Cowling, a professor in the School of Public Health at the University of Hong Kong, said though the final case fatality rate was as yet unclear, he expected it to increase beyond the current 4.9% in Wuhan and 2.1% across the country.

“The current estimates are only based on cases who have already died and do not include people currently in a serious condition who unfortunately may not survive this infection in the coming weeks,” he said.

That can be a significant bias when an epidemic is growing quickly, said Marc Lipsitch, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health who previously studied the spread of the deadly 2002-3 SARS outbreak and the 2009 swine flu pandemic. “If we count (unresolved cases) … we are missing some of the fatalities that will later happen among those cases,” Lipsitch said. True case fatality rates take the number of people who were infected with a disease and give the proportion of deaths versus recoveries.

But there’s also a big potential bias the other way, said Inglesby. “Wuhan’s public health authorities have said they don’t have the capacity to test all of the mild cases, so at least a portion of those people will not be counted,” Inglesby said. “It may be that there’s a very large number of people who have been infected and are either asymptomatic or have only mild disease.” A significant uptick in mild cases could be expected to lower the overall case fatality rate.

“At the beginning of an epidemic you usually see the more severe cases. Any place that sees milder cases is going to get a more accurate, and lower, case fatality ratio,” Lipsitch said.

That may partly explain why the ratio is so much higher in Wuhan, where hospitals are straining under the burden of more serious cases, than in other parts of the country where fewer severe infections have been recorded.

Inglesby added that information disclosure problems in some areas and overly narrow screening guidelines could also affect who gets tested, and hence the proportion of recorded deaths from the disease.

Ultimately, the effects of the different biases will become apparent in time. “During SARS … people were underestimating the case fatality risk because they hadn’t accounted for the lags (in the number of deaths),” Lipsitch said. But during the 2009 flu pandemic, the number of mild cases was a far more significant factor. “We were seeing very severe cases at the beginning, but ultimately the real case fatality ratio was orders of magnitude lower.” So it’s really a matter of which bias is stronger.

Questions over the virus’s true deadliness haven’t stopped countries and territories across the world from taking dramatic measures to contain its spread. Last week, the U.S. and Australia imposed entry bans on foreign nationals who recently traveled in China. Others, including Hong Kong, India, Russia, and some EU countries, have imposed quarantines or travel restrictions.

Chinese authorities have placed cities under unprecedented lockdown, rolled out mandatory quarantine regimes, and extended the Lunar New Year holiday.

“Varying definitions of the case fatality rate directly affect how governments around the world react to it,” Inglesby said. “If it turns out that the rate is on a par with seasonal flu — around one death per 10,000 people — then governments would be likely to develop responses and public statements in line with how they treat seasonal flu.”

But if the rate is substantially higher than that and sustains an effective reproduction number of more than two — in other words, if each infection on average causes two more — “then governments will react with higher urgency and the pressures on health care systems will be greater,” Inglesby said.

Analysis of the confirmed cases in China suggests that the virus poses a greater threat to men, older people, and people with underlying health conditions, Jiao said at Tuesday’s press conference. Two-thirds of all recorded deaths so far have occurred in men, with 80% striking down people over the age of 60 and 75% hitting those with additional ailments like diabetes, heart disease, and tumors. The latter two groups are naturally at higher risk of death from pneumonia regardless of whether the infection comes in the form of the coronavirus or another pathogen, Jiao stressed.

No specific formula currently exists for determining the full recovery rate of infection with the new coronavirus, Jiao said. Those who do get better spend an average of more than nine days in hospital, but in Hubei that figure is 20 days due to a large number of serious cases there and stricter standards in Wuhan for discharging patients, she added.

Additional reporting by Zhou Dongxu.

Contact reporter Matthew Walsh (matthewwalsh@caixin.com) and editor Flynn Murphy (flynnmurphy@caixin.com)

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR