In Depth: How Wuhan Lost the Fight to Contain the Coronavirus

|

|

|

This is the first part of Caixin’s exclusive four-part in-depth report on China’s fight against the coronavirus outbreak. Please click here to check out part 2 and part 3.

(Wuhan) — Zhang Qi was planning to spend a week of leisure in Wuhan when he arrived Jan. 21. It looked like any other day in the historic, prosperous central China metropolis of 11 million people.

That sense evaporated in the evening as Zhang watched renowned epidemiologist Zhong Nanshan issue a sobering warning in a TV interview. A new form of viral pneumonia was showing signs of spreading among people in the city and had already sickened a number of medical workers, Zhong said.

“I felt something was wrong,” Zhang said.

His plans as a tourist abruptly changed early on the morning of Jan. 23. News popped up on Zhang’s phone that the Wuhan government would lock down the city in several hours for disease control, halting all outbound air, rail and bus services. Zhang quickly packed and rushed to the main railway station.

“I am just a tourist,” Zhang told Caixin before he boarded a train back home to Beijing. “I don’t want to be trapped in this dangerous city.”

The Wuhan government announced its decision to “lock down” the city at 2 a.m. that day, effective from 10 a.m. Nobody knew what the lock-down would mean and how long it would last. In those 8 hours of uncertainty, anxiety and panic, hundreds of thousands of people rushed out of the city via whatever means they could find. There were 9 million residents left.

At 10 a.m., the 121-year-old Wuhan railway station closed its doors. Wuhan cut off its airports, railways, roads, waterways and even mail. The city was isolated.

About 5 kilometers (3 miles) away, infectious disease doctor Zhao Lei at Wuhan Union Hospital was still sleeping. He was exhausted by the sudden surge of patients over the past month. Since late December, people with fevers and pneumonia-like symptoms had been flooding in, forcing the hospital to expand the fever clinic from one floor to almost the entire building. There could be as many as 900 fever patients in one day.

What’s more, a few nurses in the neurosurgery department had fevers too. They had all treated one patient, who had surgery on Jan. 7. The 69-year-old patient started to have a fever four days after surgery, and his CT scan showed signs of lung infection. This patient was transferred to Zhao’s infectious disease department, but not before he infected a total of 14 medical staff. This case was cited by experts and officials as clear evidence of human-to-human transmission when the lock-down was imposed, and the patient was deemed the first identified super-spreader of the new coronavirus.

Beijing was deserted during the normally convivial holiday, as people were encouraged to stay home. Medical experts say they think the coronavirus has an incubation period of as long as 14 days, so strict limits on movement of for at least two weeks from the Wuhan lockdown will be a crucial measure for containing the disease.

|

The Hankou station in Wuhan is locked down for the first time in its 121-year history at 10 a.m. Jan. 23. |

“Shutting down the city was no surprise as it is an effective way to prevent disease from spreading,” Zhao said.

But there was no precedent worldwide for putting a city as big as Wuhan under complete quarantine. Over hundreds of years, Wuhan, the capital of Hubei province, has played a critical role in central China as an economic and transportation hub connecting major parts of the country via an extensive network of road, railway and water routes on the Yangtze River. During the Qing Dynasty, Wuhan was known as the “Thoroughfare to Nine Provinces.”

For most of Wuhan’s residents, nothing seemed unusual, although word was circulating about a mysterious disease. As the quarantine order fell and more timely information was published, they found themselves at the epicenter of a new pandemic known as novel coronavirus, or 2019-nCoV. Although the origin of the deadly virus hasn’t been clearly confirmed, it is believed to have spread from Wuhan to the rest of China and around the world.

Things moved quickly after the quarantine order. Three days after Wuhan cut itself off from the outside, it halted all public transport inside the city. In six days, almost all other cities in Hubei imposed similar lockdowns. By Jan. 29, all of the 31 provincial-level regions in the Chinese mainland enacted top-level emergency responses to the virus. More than 6,000 medical workers have been dispatched from across the country to Wuhan.

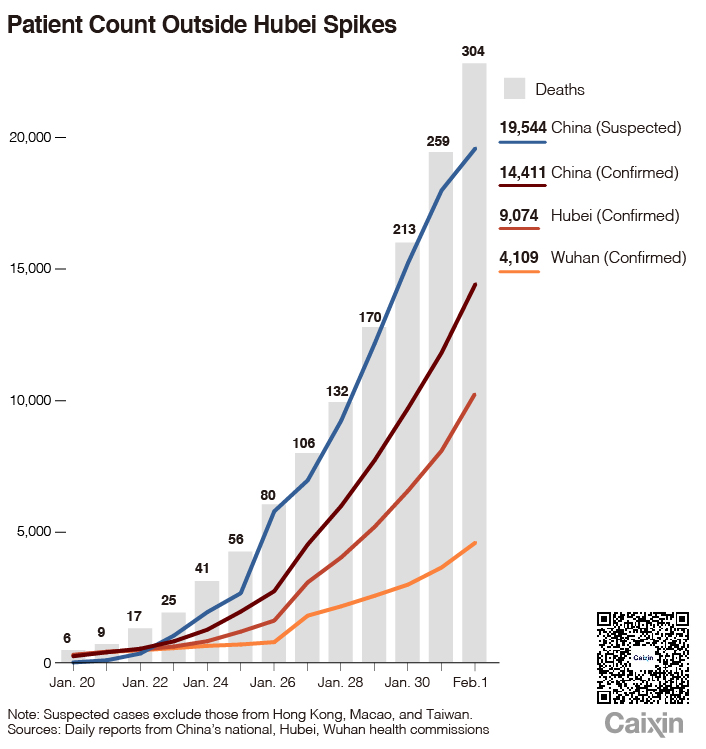

But the measures have yet to stop the virus from spreading. Casualty numbers continued rocketing over the past week. As of Saturday, 11,821 coronavirus infections were confirmed across China with a death toll of 259. Hubei alone reported 7,153 confirmed cases and 249 deaths, including 192 in Wuhan. The virus has also spread globally as 134 cases have been confirmed in 23 countries, spurring several countries to impose travel bans on China.

On Thursday, the United Nations’ World Health Organization (WHO) declared the coronavirus outbreak a global health emergency while emphasizing its confidence in China’s capacity to control the outbreak. WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus praised China’s efforts to contain the outbreak, saying he had never seen a nation respond so aggressively to a disease.

Read More

Coronavirus Whistleblower Li Wenliang Dies of the Disease

Whistleblower Doctor Who Died Fighting Coronavirus Only Wanted People to ‘Know the Truth’

Opinion: China Needs to Institutionalize Whistleblower Protection

Since the Wuhan lockdown, many major Chinese cities have sought to contain the virus by restricting transit or extending the Lunar New Year holidays. Streets in many cities including Beijing were deserted during the normally convivial holiday, as people were encouraged to stay home. Medical experts say they think the coronavirus has an incubation period of as long as 14 days, so strict limits on movement of for at least two weeks from the Wuhan lockdown will be a crucial measure for containing the disease.

Now China is fighting a war against the virus, which has cost the economy heavily and disrupted the lives of ordinary people, especially those in Wuhan. As the country gradually recovers from the shock and fear inspired by the virus, many questioned why the virus crisis spread so quickly in Wuhan and whether there was any chance of a better outcome.

|

The demon returns

Word circulated online since late December that a mysterious pneumonia was spreading in Wuhan, recalling Chinese people’s painful memory of the SARS epidemic in 2003, which claimed nearly 800 lives.

On Dec. 30, a document from Wuhan’s public health authority went viral on the internet, confirming that the city’s hospitals had received a rising number of patients who showed pneumonia-like symptoms. All the patients had contact with the South China Seafood Wholesale Market in downtown Wuhan, according to the document.

Established in 2003, the 30,000-square-meter market accommodates more than 1,000 merchants selling a wide range of farm products and seafood. The market supplies almost all the restaurants in Wuhan and neighboring areas.

“Without the market, the whole catering industry in Wuhan would stop,” a vendor told Caixin.

It is widely believed that the market, which is home to a gray market for trade in wild animals, is also where the virus started its journey around the world.

On Dec. 31, one day after the city health officials’ warning, the Wuhan city government for the first time disclosed that 27 pneumonia cases were confirmed in the city including seven severe cases and two recoveries.

On the same day, a team of public health experts from the National Health Commission arrived in Wuhan to investigate the mysterious disease. Meanwhile, a group of epidemic prevention workers were sent to the seafood market for disinfection. “The market was closed, cleaned up, and the ‘crime scene’ was gone. How can we resolve the case without evidence?” said Guan Yi, director of the State Key Laboratory of Emerging Infectious Disease at the University of Hong Kong. “Tracing the pathogen is a complicated process. We can’t just find an infected animal and determine that was the origin.”

The next morning, a notice posted at the South China Seafood Market ordered it to be closed for “environmental and sanitation rectification.” As vendors packed to leave, unease grew among them about a rumored epidemic.

“The seafood market has been known for its dirty environment for years,” said a resident living nearby. “There is always the smell of seafood and dead poultry.”

Unknown origin

People familiar with the South China Seafood Market know that it is not only a place to find a rich variety of seafood but also exotic wild animals sold by vendors in deep corners of the market.

There have always been vendors “selling snakes, pheasants, giant salamanders, crocodiles and hares,” said a merchant at the market. Most of the wild animal vendors were located at the western part of the market, the merchant said.

Trading certain wild animals including live ones is prohibited by Chinese laws and industry regulations. Although market authorities conduct regular inspections and impose heavy fines on violators, sales of wild animals at the market have never been stopped in the past decade, vendors told Caixin.

According to research published Jan. 26 by the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 33 among 585 environmental samples extracted from the market tested positive for the virus. Of the positive samples, 93.9% came from the western part of the market.

The CDC later reported that the new coronavirus was very likely passed from certain wild animals to humans at the South China Seafood Market and then evolved into human-to-human transmission.

While all eyes are on the seafood market, some experts said the situation may be more complicated. An essay published by The Lancet medical journal said that while wild animals are the most likely source of the virus, there was more than one venue where the virus was passed to humans. The essay, penned by doctors at Wuhan Jinyintan Hospital, found that only 27 of the first 41 patients diagnosed with the coronavirus infection in Wuhan had contact with the South China Seafood Market.

“Now it seems clear that (the) seafood market is not the only origin of the virus,” said Cao Bin, one of the essay’s authors quoted by ScienceInsider, a publication of the 172-year-old American Association for the Advancement of Science. “But to be honest, we still do not know where the virus came from.”

|

Patients pack the hallway of the Red Cross Hospital in Wuhan on Jan. 22. |

Muted warnings

Doctors on the front lines of epidemic outbreaks always sense the danger ahead.

Zhao Lei at the infectious disease department of the Wuhan Union Hospital said he received the first patient suspected with coronavirus infection in December. The patient’s pneumonia symptoms were quite unusual, and a CT scan showed shadows in his lungs, Zhao said. Although CT scan results are not the only reference for coronavirus diagnosis, they are a key indicator.

In the following days, patients with similar symptoms started to flood into the hospital, sometimes reaching 800 or 900 in one day, Zhao said. The hospital had to transfer more doctors and nurses to the fever clinic to treat the influx of patients.

Several doctors raised concerns of a new strain of virus that showed stronger contagion and severity than normal respiratory infections, but they were confused by health-care authorities’ hesitance to take measures and official statements declaring the disease controllable.

Li Yunhua, a radiologist at the Hubei Xinhua Hospital in Wuhan, said he first heard of some patients with SARS-like symptoms in his hospital Dec. 30. That night, Li received messages from an online chat group of doctor colleagues in several Wuhan hospitals who warned of a new epidemic emerging in the city.

But the next day, Li said he felt a little relieved when the Wuhan health authority issued a public statement saying there were 27 confirmed pneumonia cases with no sign of human-to-human transmission. No medical worker had been infected, according to the statement.

The following day, Wuhan police said eight people were punished for spreading rumors online, and the government reassured the public that there was “no obvious human-to-human infection,” or “cases of medical staff being infected.”

What Li witnessed was arguably the most significant whistleblowing case in China’s medical history. The eight were mostly doctors who sent disease warnings in various chat groups on Dec. 30. Among them was Li Wenliang, an ophthalmologist in Wuhan, who shared with an instant messaging group chat that the ophthalmology department in his hospital had put seven patients from a local seafood market who were diagnosed with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) into isolation wards.

The punishment of the eight “rumor spreaders” was widely reported by the police, local media and Wuhan health authorities. It silenced many doctors, Li said, and although more of them sensed the danger of the disease they were afraid of “being called in by the police.”

The official infection number looked severe but not too worrisome. However, the Wuhan government suspended updating the infection numbers between Jan. 5 and Jan. 10. It didn’t explain the reason, but it coincided exactly with an annual meeting of provincial lawmakers. When briefings resumed Jan. 11, the government again said there were no medical worker infections or evidence of human-to-human transmission, while reporting that the number of infections declined to 41.

“All doctors in our hospital knew it was not correct as it was so different from what we’d seen,” said a doctor at a large public hospital in Wuhan on condition of anonymity.

A radiologist at another public hospital also raised doubts about the official statistics.

“On Jan. 15, I found 50 cases (with lung infections shown on CT scan), but the health commission still reported 41, unchanged from Jan. 11,” he said.

Doctors sickened

Li noticed an infection on Jan. 6 in a CT scan of a respiratory doctor in his hospital. The doctor had never been to the South China Seafood Market, Li said. But officials at the hospital ordered doctors to not disclose any information to the public or the media, Li said.

Li was shocked by the surge of patients with lung infections. Since Jan. 3, “it started at two to three per day and increased to four to five the next day, and then the number doubled every three to four days,” Li said. On Jan. 18, Li read 86 CT scans with lung infections, and after that more than 100 cases every day.

Even the CT scan machine refused to work under the strain, and shut down regularly. The number of diagnosed infected lungs finally stopped rising in Li’s department — because the machine reached its maximum reading capacity.

“I’ve never seen a virus grow so quickly,” Li said. “The speed is stunning.”

Li’s colleague Liang Wudong underwent a CT scan Jan. 16 after showing symptoms of fever.

“The whole lungs were infected,” Li said. Liang was transferred to Jinyintan Hospital Jan. 18 and died a week later.

As more and more medical staff grew sick, the atmosphere in the hospitals became tense. Li said that his hospital refused to disclose the fact that medical professionals were infected, and even came up with a strange requirement – CT scans of hospital staff were not allowed to be given to the person.

Caixin interviews with several doctors from different hospitals in Wuhan found the same decree – the test results of medical staff cannot be disclosed. If a test came out positive, the person would be notified by phone.

It is still not clear who gave the order to the hospitals to hide the fact that medical staff were infected.

Outside its hospitals, Wuhan seemed to operate normally, warming up to embrace the most important holiday of the year. On Jan. 19, a massive community dinner was held with 40,000 households eating together to celebrate the New Year.

It wasn’t until Jan. 20 that the public became aware of the risk of human-to-human transmission. On January 20, Zhong Nanshan, a leading authority on respiratory health who came to national attention in his role fighting SARS, confirmed in a TV interview that the 14 medical workers infected in the neurosurgical department in Wuhan Union Hospital caught the virus from the super-spreader.

The next day, the Wuhan Municipal Health Commission confirmed for the first time that 15 medical workers were infected. But sources close to the matter said the actual number was much higher.

Li told Caixin that as of Jan. 29, more than 30 medical workers at his hospital were suspected of being infected.

On Jan. 28, China’s Supreme Court corrected the Wuhan police’s punishment of the eight people who first flagged the danger of the coronavirus outbreak online. In a statement published on its social media account, the top court said “if the ‘rumor’ was heard by the public and led some of them to start protection, we would be in a better position of disease control.”

A research report jointly published by the CDC and the Hubei Disease Prevention and Control Center Jan. 29 said evidence showed that the new coronavirus started passing from patients to their close contacts in mid-December.

While the paper provided hard evidence that vindicated the doctors under gag order, it too became a center of controversy.

The authors of the report based their conclusions on a study of 425 people who had been infected with the coronavirus since December. Of those, 15 were medical workers — seven were confirmed as having contracted the disease between Jan. 1 to Jan. 11, and eight during the period from Jan. 12 to Jan. 22.

“There is evidence that human-to-human transmission has occurred among close contacts since the middle of December 2019,” the paper said in its conclusion.

It went viral on Chinese social media and prompted a wave of angry comments from internet users. Many were questioning whether health officials from CDC withheld critical information from the public.

CDC issued a statement, saying the paper’s conclusion was made retrospectively.

Contributors to the paper including Feng Zijian, a deputy director at the Chinese CDC, and Gao Fu, a director, have spoken to Caixin about the study. Feng told Caixin the center only obtained the data related to the 425 cases on Jan. 23 and immediately began its research and analysis. Its contributions to the paper were submitted on Jan. 25 and 26.

But Feng and Gao dodged the question about when they first learned about the infection of medical staff.

|

Nurses wearing protective gear prepare to enter the quarantine zone at the Wuhan Red Cross Hospital Jan. 24. |

Struggles in Wuhan

Wuhan’s approach towards the disease suddenly switched from slow motion to decisive action.

Wuhan Mayor Zhou Xianwang on Jan. 29 acknowledged that the city had failed to disclose information on the coronavirus outbreak in a timely way, and offered his resignation over the Jan. 23 decision to lock down the city.

However, the mayor said he was complying with rules for information disclosure under the country’s infectious disease prevention law.

All of Wuhan was locked down from Jan. 23. But was it ready?

Xie Zuoliang, 69, felt he had a fever and went to Wuhan Xinhua Hospital on Jan. 19 for a CT scan. The result showed an infection in his lungs. The doctor told him that only designated hospitals could admit patients with a fever at that time, according to a new city government policy. In other words, he needed to check in to a different hospital.

Early the next day, Xie arrived at the Wuhan Union Hospital in hopes of seeing a doctor but found hundreds of people queuing up ahead of him. He gave up waiting after five hours.

The next morning, Xie rushed to another designated hospital — Wuhan Xinhua Hospital — but was again stopped by the long queue. A busy nurse told him the hospital was completely full.

On Jan. 22, Xie said his hopes rose after hearing news that the Wuhan government cleared more medical facilities to receive patients suspected of coronavirus infection. He went to the Red Cross Hospital but was shocked by the chaos — desperate patients angrily shouting at doctors while exhausted medical staff could barely hold themselves up. A young doctor cried out to his supervisor begging for a break.

“I felt both doctors and patients were in despair,” Xie said.

|

The construction site of a new quarantine hospital to admit coronavirus patients in suburban Wuhan Jan. 28. |

Xie got some prescription medication after seven hours of waiting but was told there was no room for him to be hospitalized. Failing to find a taxi, Xie walked more than an hour back home in the middle of the night.

The chaos in hospitals was partly caused by the frequent policy changes by city health authorities, causing confusion to patients and institutions, Li said. But more importantly, it reflected how the government and the public were stunned by the fast-spreading virus after the long absence of true information.

Li said he feels guilty for not disclosing the truth to the public earlier on.

“Doctors and disease prevention officials have known how serious it is, but none dared to speak out,” Li said. “We should have taken the risk and spoken up.”

“Now us medical workers work days and nights to race with death to save the patients. They are all human beings living in one city with us. They don’t deserve such pain.”

Qin Jianhang, Zhang Shulin, Peng Yanfeng, Di Ning, Yang Rui, Huang Yuxin and Huang Yanhai contributed to this story.

Contact reporter Han Wei (weihan@caixin.com) and editor Bob Simison (bobsimison@caixin.com)

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR