In Depth: What Will Chinese Apps Do After India Ban?

An hour after the Indian government announced a ban on 59 Chinese apps late last month, Chinese residents in this South Asian country rushed to leave alternative contact information for friends on WeChat.

“You can find me through Alipay if India really cuts off WeChat,” read one posting, for example, on the Chinese social media platform that was among the banned mobile applications.

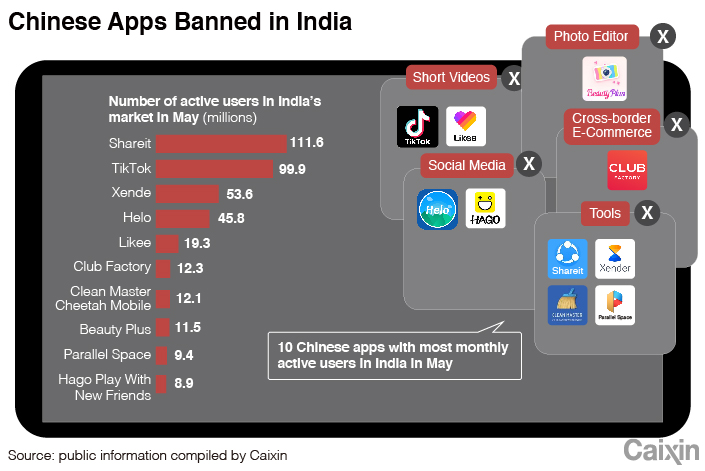

Days later, the Google Play Store and the Apple Store removed all 59 of the apps in India, including short video platform TikTok with 200 million users in India, Tencent’s WeChat, Sina’s Weibo, Baidu Map and Alibaba’s UC Browser.

The government action is not only forcing local users to scramble to switch to alternatives but is also forcing Chinese tech companies to rethink their strategy in the nation of 1.35 billion people, the world’s second-largest population after China’s 1.39 billion.

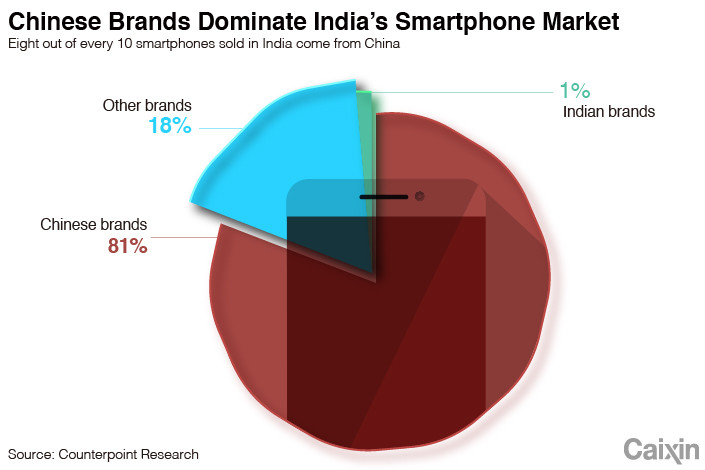

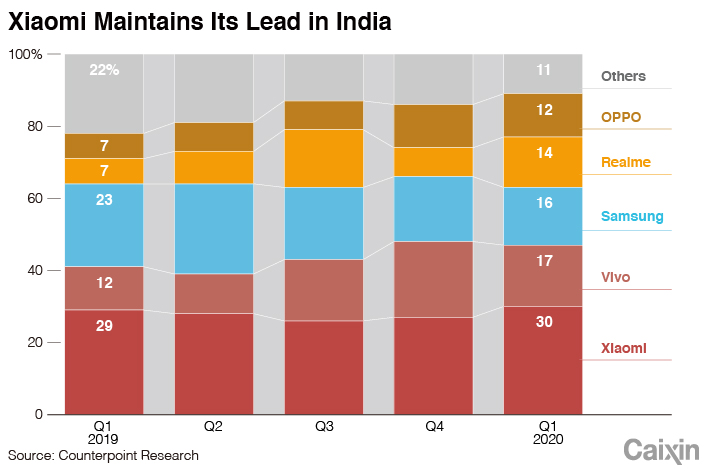

India and Indonesia, reflecting a demographic dividend of youthful populations, have become the most important markets for Chinese tech companies in recent years. With rapid growth in smartphone penetration, the Indian market is particularly appealing for mobile phone hardware and short video and game applications. ByteDance Ltd., owner of TikTok, projects a loss of more than $6 billion over an unspecified period after three of its apps were banned.

Policy shift

The unprecedented exclusion took place against a backdrop of strained relations between China and India and came days after a border clash in the Himalayas left 20 Indian soldiers dead. Even before that confrontation, India’s policy toward Chinese internet companies was growing more hostile.

To curb opportunistic foreign acquisitions of Indian companies made vulnerable during the Covid-19 pandemic, the India government in April revised its foreign direct investment policy to narrow the scope of eligible investors. Under the new rules, companies from countries that share a land border with India will be permitted to invest only with government approval rather than automatically as previously allowed.

Read More

Cover Story: Will TikTok Be the Next Huawei?

Given the limited investment capability of India’s other neighbors — Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Myanmar, Bhutan and Afghanistan — the new rules effectively target Chinese investors.

This requirement has already delayed many projects by Chinese investors, according to Indian law firm Link Legal, which advises several Chinese companies.

The Himalayan border dispute escalated anti-China sentiment among many Indian citizens. In May, an app called Remove China Apps, which enabled users to easily delete apps developed by Chinese enterprises, was downloaded more than 5 million times in India before it was pulled from the Google Play Store.

|

Facebook is biggest winner

There are many forces behind India’s ban on Chinese apps, and the border conflict was just a trigger, said Lin Minwang, deputy director of the Institute of South Asia Studies at Fudan University. American apps such as Facebook and Indian local tech companies want to drive their Chinese rivals out of the Indian market, he said.

With the Chinese apps kicked out, Facebook and Indian apps will become the biggest winners. Facebook’s messaging app WhatsApp and photo and video-sharing platform Instagram entered the Indian market in 2010 and had long been at the top of the most-downloaded nongame apps in the country before Chinese rivals came.

Facebook and its Messenger app ranked as the top two most-downloaded nongame apps in India in 2018, and WhatsApp ranked fourth, while TikTok was sixth, according to mobile data and analytics platform App Annie.

Within just a year, Chinese internet companies changed the Indian app landscape. Among the top 10 most-downloaded apps in India, five were Chinese. TikTok took over the top position from Facebook. Other Chinese apps that quickly gained popularity included another short video platform Likee, social media app Helo, cross-platform web browser UC Browser and video editing and sharing app VMate. Even though these Chinese apps’ monthly active users were no match for Facebook’s apps, their functions cover almost all of the same aspects.

Facebook is eager to grab back market shares as it has spent billions of dollars in the market. In April, the U.S. social media giant paid $5.7 billion for a 9.99% stake in Jio Platforms, the digital technology arm of Indian billionaire Mukesh Ambani’s conglomerate Reliance Industries. It is also the parent company of top Indian mobile carrier Reliance Jio, which claimed 387.5 million mobile subscribers at the end of 2019.

Some may choose to exit

Not all Chinese companies affected by the ban take as much of a hit as ByteDance, which makes them view the ban differently.

ByteDance, with its valuation potentially greatly affected by losing its largest overseas market, is expected to aggressively pursue exemption from the ban, while some Chinese companies may look to sell or abandon the market because they see little hope in capitalizing on their market shares, according to Lin Meihan, partner of India Renaissance Capital, a provider of financial advisory services to Chinese internet companies in India.

Still, some have already taken measures to sidestep a ban. Xiaomi, for example, is marketing its products as “Made in India” to take advantage of manufacturing or assembling domestically many of the devices it sells in India.

|

Two apps by Xiaomi — Mi Community and Mi Video Call — are on the banned list, but its main video sharing app, Xiaomi Video, is exempt. An employee at Xiaomi’s Indian office said the company is surprised that the two apps were included in the ban list because they have nothing to do with data security and privacy.

“We are an Indian company, as more than 99% of our phones sold in India are made locally, and 65% of these components are locally sourced or locally manufactured,” said Xiaomi India Managing Director Manu Kumar Jain.

Even though apps developed by local companies with Chinese investors are not on the banned list, market expectations for investment in India have changed fundamentally. Many expect the investment environment to continue deteriorating.

In a televised address to the nation May 12, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi pushed for a self-reliant India. Many see this call as a sign that the government is trying to replace Chinese goods and services with locally made products to reduce the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on local businesses.

One option for Chinese companies is to form joint ventures with local businesses. New Delhi has long adopted a “carrot and stick” approach to Chinese investment, hoping Chinese investors would deepen ties with local businesses rather than just doing business there, according to Link Legal.

Contact reporter Denise Jia (huijuanjia@caixin.com) and editor Bob Simison (bobsimison@caixin.com)

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR