Weekend Long Read: How Chinese Society Fell Out of Love With Marriage

Marriage is the foundation of a Chinese family. For individuals, tying the knot means an emotional connection — a sense of belonging to a family. Furthermore, a long-term harmonious marriage contributes to the stability of society. However, in recent years, the country’s divorce rate has been rising.

There has been a change of mindset: young people are now pursuing independence and see wedlock as a padlock. At the same time, it is more difficult for them to start their own families due to the high costs of getting married and raising children. Some young people don’t want to get married, let alone bring a child into this world. China’s declining marriage and birth rates, along with an aging population, are reinforcing each other.

Let’s take a look at what’s behind China changing attitude toward marriage.

Fewer, later, greater chance of failure

As the Chinese economy has grown, the country’s marriage rate has declined, its divorce rate has risen, and people are waiting until they are older to tie the knot.

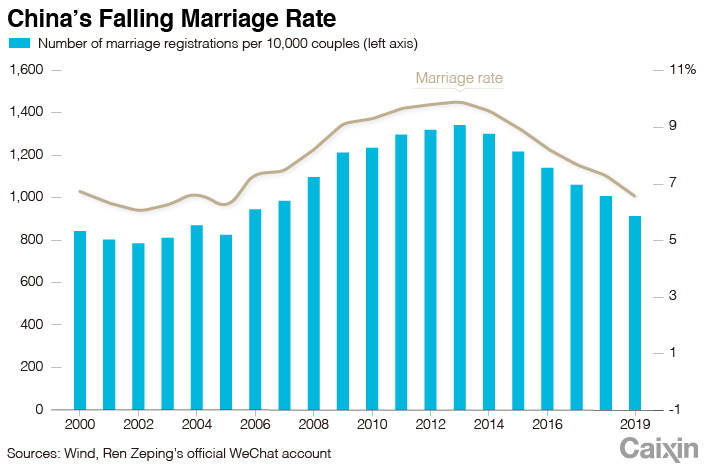

A telling number is China’s marriage registrations, which have been in decline since 2013, when they hit an all-time high of 13.47 million. In 2020, the number fell 12.15 million to 8.13 million. Specifically, the number of first marriages dropped from 23.86 million in 2013 to 13.99 million in 2020, while the number of remarriages increased from 3.08 million to 4.56 million.

|

Then there is the age factor. Chinese people are increasingly getting married later. The largest age group of people getting married in China is now 25-29, compared with 20-24 in the past, while the number of people over the age of 40 registering get married has risen sharply.

Meanwhile, China’s divorce rate has been climbing. Between 1987 and 2020, the number of divorce registrations in the country surged from 580,000 to 3.73 million, with the divorce rate rising from 0.5% in 1987 to 3.4% in 2019.

|

Higher growth, fewer marriages

Most parts of China have witnessed a declining marriage rate since 2013. Generally, there is a negative correlation between a region’s GDP growth and marriage rates.

In general, China’s more developed regions, like its coastal provinces, have lower marriage rates than the rest of the country. In 2019, Shanghai, Tianjin and the provinces of Zhejiang, Shandong, Guangdong and Fujian had some of the lowest marriage rates in the country, with Shanghai’s the lowest at 4.1%.

But marriage rates are generally high in China’s western and less developed regions.

Migration and aging have also influenced the trend.

The provinces of Liaoning, Shandong, Sichuan, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, and Anhui, as well as the municipalities of Shanghai and Chongqing, were the fastest aging regions in China. Regions with slower growth and larger population outflows have higher divorce rates than elsewhere in the country. Married couples in those provinces often have to live and work in different places, which is the major reason why they get divorced.

More choice for women

The rising education level of the population is also playing a role in delaying marriage.

According to data from the National Bureau of Statistics, between 2015 and 2019, the number of postgraduate students surged from 1.59 million to 2.4 million. As more people spent more time getting educated, the average marriage age rose.

In 1982, the average person in China spent 5.3 years in school. By 2017, the figure had risen to 9.6 years. From 1990 to 2016, the average age of a man getting married increased from 24.1 to 27.2 and the figure for women rose from 22 to 25.4.

Women have started outnumbering men in higher education programs in China. In 2017, the proportion of women in higher education reached 52.2%, up from 38.3% in 1998.

Over roughly the same period, the number of single women has grown rapidly. From 2000 to 2015, the number of unmarried women over 29 soared from 1.54 million to 5.9 million. In 2015, the share of unmarried women over 29 with a master’s degree was as 11%, compared with 5% of women with a bachelor’s degree or less education.

As women have gained economic independence, they have become better able to face the adverse consequences of divorce. According to a report by the Justice Big Data Institute, Chinese courts adjudicated more than 1.4 million divorce cases in 2017. Of these cases, 73% were brought by women.

Marriage costs

Traditionally, marriage in China is accompanied by a series of events — all of which are costly. Currently, skyrocketing property prices and children’s education costs are deterring young people from tying the knot, especially in large cities.

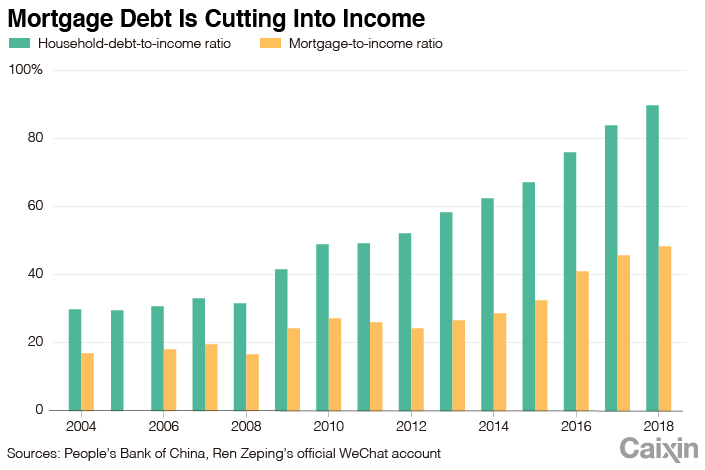

China’s housing prices have been rising sharply since 1998, stressing out newlyweds and their parents. Between 2004 and 2018, the outstanding value of individual housing loans increased sixteenfold from 1.6 trillion yuan to 25.8 trillion yuan. In 2018, these mortgages accounted for 54% of residents' total loans.

During this period, China’s mortgage-to-income and household-debt-to-income ratios both jumped. And because some homebuyers took out consumer loans to help make their down payments, the real debt-to-income ratio could be even higher.

|

Falling birthrates, too many boys

The one-child policy, introduced in the late 1970s, has created two alarming problems that have hurt China’s marriage rate — declining birthrates and a growing gender imbalance.

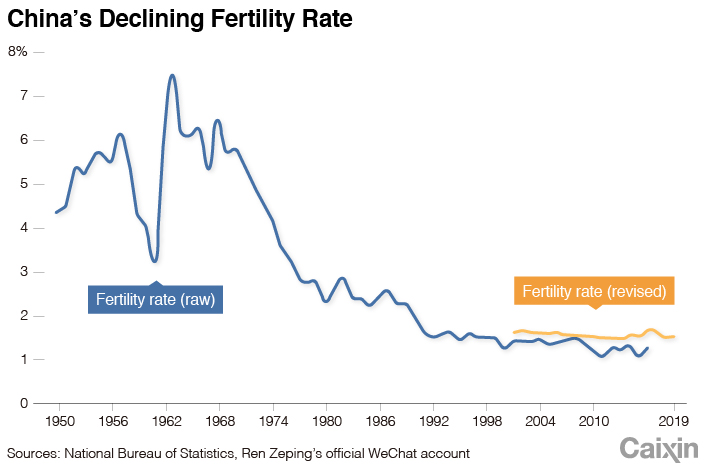

Lower birthrates have had a long-term impact on the number of people of marriageable age. According to 2010 census data, China had 219 million people born in the 1980s, 188 million born in the 1990s, and 147 million in the first decade of the 2000s.

At present, people aged 25 to 29 make up the largest group of newlyweds, but the number is falling fast.

From 1979 to 2019, China’s birthrate plummeted from 17.8% to 10.5%, even though the government relaxed the one-child policy in 2015. Since that policy was introduced, the country has suffered a growing gender imbalance, with men outnumbering women.

In 1982, there were 107.6 boys born for every 100 girls. The figure rose to 110 in 1990, and to118 in 2000. It has since exceeded 120.

According to 2010 China’s Census data, the ratio has grown to the point that indicates there are 13 million more than women than men in the generation born in the 2000s.

Negative effects

Just as many Chinese people are delaying marriage, many are also having children later in life. From 1990 to 2015, the average age of first-time mothers increased from 24.1 to 26.3.

In China there is a growing trend of people getting married and having children later in life, which has created to growing senior-care burden that could become serious drag on the country’s economy.

China will emerge as one of the countries with the highest financial burden for senior care. Take pensions for example. From 2015 to 2019, the average growth rate of the country’s pension fund revenues was 14.5%, but the same figure for expenditures was about 17.2%. In 2019, there were 16 pension funds in provinces and administrative units that didn’t bring in enough revenues to cover their expenditures. The northeastern province of Heilongjiang has been unable to make ends meet since 2013, and its pension shortfall in 2019 was 43.37 billion yuan.

|

Recommendations

China should take measures to help people who can’t afford to get married and raise children. The governments should introduce a comprehensive package of pro-family measures, covering housing, education and health care.

• First, the government should continue to follow President Xi Jinping’s mantra that homes are for living in, not for speculating on.

• Second, the government should improve women’s employment rights. For one thing, policies for maternity leave and breastfeeding leave should be further put into effect. The extension of maternity leave and paternity leave should be guaranteed. For another, employers should be offered tax incentives to reduce the costs they incur when their employees have children. A reasonable and effective burden-sharing mechanism should be built among the state, employers and families.

• Third, China should boost spending on public education. The country should try to set up a comprehensive package that covers the cost of raising a child to 18 or the end of their college career. It should include welfare policies for prenatal care, hospital delivery, child care, education, family tax credits, and providing direct financial benefits to lower-income people.

• Fourth, the government should offer child-care services and related benefits to families. The country’s nine years of compulsory education should be extended to 12 years.

• The government should encourage employers to set up child care facilities. At the same time, they can motivate grandparents to take care of their grandchildren to take some of their pressure off parents.

• Most importantly, China should fully liberalize childbearing immediately. The country’s third baby boom peaked in 1987. People who were born during the middle to late period of that boom are still under 35 — their prime childbearing age. Once we miss this opportunity, it will become much costlier to increase the number of births.

We first recommend that China allow all couples to have three children. The incremental reform will ease concerns from conservatives that the country’s population will explode. All in all, related steps should be introduced as soon as possible.

Ren Zeping is the chief economist and director of the Evergrande Think Tank. Li Xiaotong and Hua Yanxue are analysts at the Evergrande Think Tank, and Zhang Jing is an intern there.

Contact translator Guo Xin (xinguo@caixin.com) and editor Michael Bellart (michaelbellart@caixin.com)

Download our app to receive breaking news alerts and read the news on the go.

Follow the Chinese markets in real time with Caixin Global’s new stock database.

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR