Cover Story: The Challenge of Keeping China From Shrinking

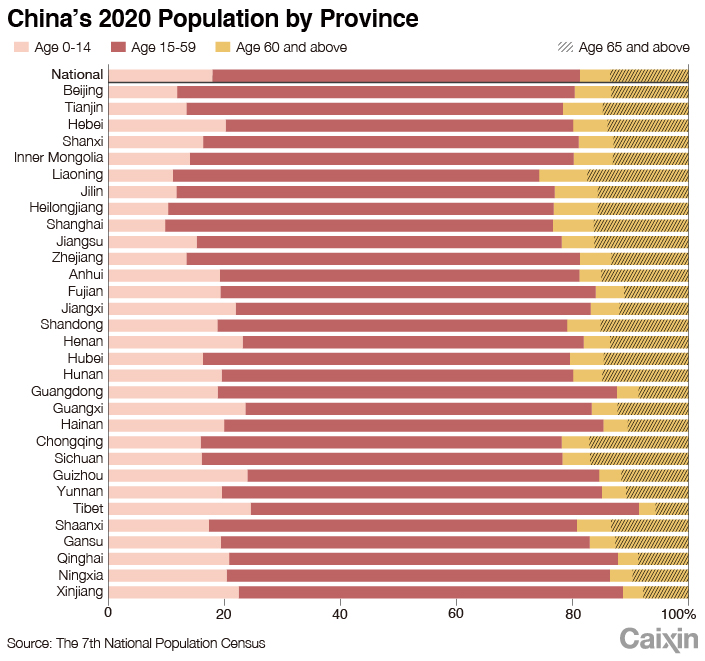

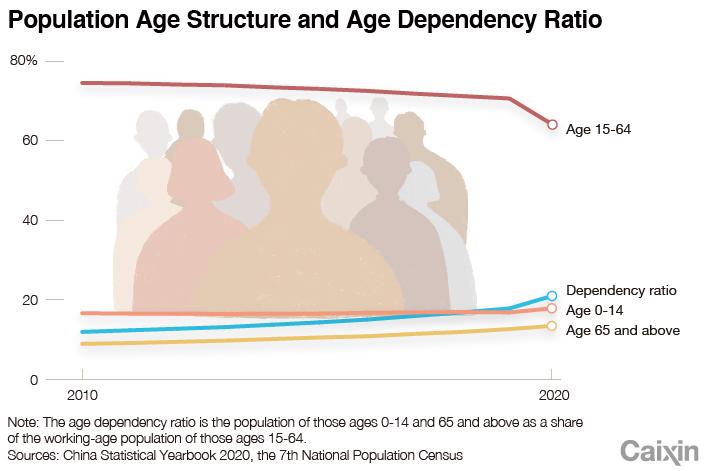

China’s once-in-a-decade census showed an ultra-low fertility rate, a shrinking labor force and a rapidly aging population, alerting policymakers of the urgent need for significant changes to reverse or at least ease a dramatic plunge in population that could sap economic growth.

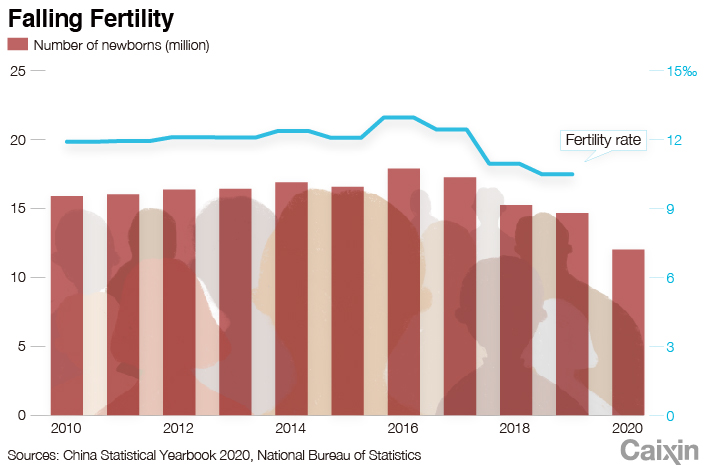

The numbers herald drastic demographic changes for China in coming decades. At present, the world’s most populated country still adds 12 million newborns every year. However, in the long run, it may be difficult to reverse the trends of an increasingly aging population and a shrinking workforce.

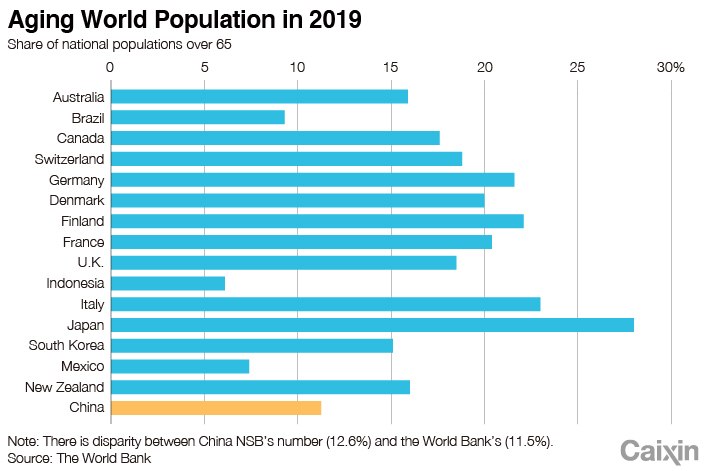

This is a global challenge. By 2050, one in six people in the world will be over age 65, up from one in 11 in 2019, and the global fertility rate — which fell from 3.2 births per woman in 1990 to 2.5 in 2019 — is projected to decline further to 2.2 in 2050, the United Nations predicted in 2019.

Low-fertility trap

Countries including Germany, Japan and South Korea are already having negative population growth. China’s transition to this stage has been particularly rapid. In a national population development plan issued in 2016, the State Council said China’s pace of aging was significantly higher than the world average. In terms of fertility rate, the 1.3 reading in the most recent census is lower than that of many developed countries such as Japan with 1.4 and the United States with 1.6. According to the United Nations, maintaining a population requires a fertility rate of 2.1.

|

“The fertility rate is so low that we have entered the stage of ultra-low fertility,” said Wang Guangzhou, a researcher at the Institute of Population and Labor Economics at the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences.

China’s 1.3 fertility rate suggests a “low-fertility trap,” a concept first raised by the Austrian demographer Wolfgang Lutz, who observed that no country whose fertility rate fell below 1.5 has reversed that trend.

The impact of fertility on economy growth will appear in two decades, said Huang Wenzheng, a demography expert at the Beijing-based Centre for China and Globalization, a think tank.

What is more alarming is that China’s fertility rate will continue to decline, as the current number includes the gradually fading accumulation effect from the implementation of China’s two-child policy, according to Liang Jianzhang, a co-founder of online travel platform Trip.com Group Ltd. and a population economist.

Since China in 2015 abolished the one-child policy, which was introduced in 1980 to reduce the number of hungry mouths to feed, the willingness to have a second child was released over a short period of time. Many women who were about to pass out of their prime childbearing ages rushed to have a second child as soon as the policy was lifted, which amplified the national fertility rate for a time, Liang wrote in an article. After taking into account the accumulation effect, the natural fertility rate is only 1.0–1.1, Liang estimated.

When the one-child policy was lifted, experts and policymakers predicted a surge in births and a gradual recovery of the fertility rate to about 1.8. In 2015, Wang Peian, then a deputy director of China’s family planning commission, projected more than 20 million newborns in 2017 and 17 million to 19 million births a year through 2020. Instead, after rising to 17.9 million in 2016, births fell in each subsequent year.

Unwilling to have more children

One major reason for the declining fertility rate is that the number of women of childbearing age, who were mostly born in the 1980s and 1990s, fell sharply from their parents’ generation as a result of the one-child policy. Women ages 15 to 49, defined as those of childbearing age, currently number about 300 million, down 20% from 2010. According to existing demographic data, the number of women ages 22 to 35, who contribute the most to the fertility rate, will decline more than 30% over the next decade.

However, the birth control policy is not solely to blame. The impact of economic, social and cultural factors on people’s willingness to have children has also come to play a significant role. The lifting of the one-child policy has had only a limited effect on young couples. Among married couples who already have one child, only 30% said they want to have a second one, according to a 2016 survey by a team led by Chen Wei, a professor of demography at the Center for Population and Development Studies at Renmin University of China.

“Notably, Chinese have switched from policy-driven birth control to unwillingness to have children,” said Chang Qingsong, associate professor at the Population Research Institute of Xiamen University. “Previously, the policy didn’t allow people to have more than one child. Now, even if the policy is relaxed, young couples still don’t want to have more children.”

A female executive in her 40s who controls several companies and gave birth to her only child at age 39, told Caixin that she has found more and more couples either don’t want to have kids or can’t afford to, especially in first-tier cities.

Extremely high housing price-to-income ratios in big cities, increasing educational pressure and cost and a less-friendly fertility environment all have further dampened Chinese people’s fertility desire, Liang said.

“The data leads us to conclude that urban China has the highest child-rearing costs of anywhere in the world, in turn leading to the lowest fertility rates in the world,” Liang wrote.

|

|

Slow in policy response

Compared with other countries that have low fertility rates, China has been relatively slow in policy response.

In a paper comparing countries’ birth policies, Mao Zhuoyan, a researcher at the think tank China Population and Development Research Center, wrote that Japan, South Korea and Singapore all had years of neutral or moderate policies before they implemented pro-birth policies.

In Singapore, the period was three years, while Japan waited 25 years to change its birth policy. In comparison, China has held at low fertility rates but implemented no pro-birth policies for at least 35 years, Mao said.

Before the latest census, experts had different judgments on China’s actual fertility rate, which led to divergent policy suggestions. The 2010 census showed a 1.18 fertility rate, but most experts estimated the actual rate at more than 1.63, citing births that were unreported to avoid punishment for violations of the one-child policy.

China entered the stage of low fertility in the 1990s. People are increasingly concerned about the consequences of long-term low fertility rates, and voices supporting liberalization of fertility policy are increasing.

Gu Baochang, a demographer at Renmin University, was one of the first scholars to call for a radical relaxation of the one-child policy. He previously told Caixin that the academic community has been calling for policy change since 2000 and was initially optimistic that the problem could be solved within two or three years.

However, the Chinese government ignored the early calls, citing a fundamental discrepancy between China’s large population and a shortage of resources and economic underdevelopment.

When newborns continued to decrease in 2017 and 2018 even after the one-child policy was lifted, many demographers argued that the two-child policy effect had not been fully realized and still recommended conservative policies.

Many experts partially attribute the low fertility rate in 2020 to people’s delay in having children during the Covid-19 pandemic. Without the pandemic, China’s fertility rate should be around 1.48 and should fluctuate around 1.4 in the next few years, estimated Zhai Zhenwu, a professor at the China Population and Development Research Center.

|

Difficult trend to reverse

In April, Wang, former deputy director of China’s family planning commission and now a member of the Communist Party’s political advisory body, called for a significant adjustment of population policy in favor of measures to encourage births. But he acknowledged that it won’t be easy.

“Today, the difficulty to encourage people to have more children is no less than or is even greater than the birth control task 40 years ago,” Wang said after the census.

In its14th Five-Year Plan for 2021–25, China vowed to actively implement a strategy to cope with the aging population and the low fertility rate, proposing measures to develop an affordable child care system and reduce childbearing and education costs.

Some of these policies are still in the research stage and some have been introduced, but the implementation is lacking, Wang said.

“For example, policies and regulations to extend maternity leave and provide paternity leave are in place, but there is still the problem of how to push forward the implementation,” he said.

Liang suggested that the government offer parents 1 million yuan ($156,000) for each newborn child in a bid to shore up the country’s declining birth rate. Education and housing reforms to reduce childbearing costs take long periods to show an effect, while the most immediate solution would be to increase family incomes by giving families with children “real money,” he said.

Liang said his research showed that it would cost 10% of China’s GDP to raise the fertility rate from the current 1.3 to the replacement level of 2.1. That amounts to 1 million yuan per child and could be allocated in the form of cash, tax relief or housing subsidies, he said.

Experts might disagree on how to solve the population puzzle, but the consensus is that even if China starts to take measures now, it will be difficult to quickly reverse the trends of aging population and fewer births.

In a 2019 paper analyzing Japan’s aging process and pro-birth policy, Wang Wei, a researcher at the Institute of Japanese Studies, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, pointed out that even after nearly three decades of implementation of pro-birth measures since the 1990s, Japan is still mired in the low-fertility trap.

Contact reporter Denise Jia (huijuanjia@caixin.com) and editor Bob Simison (bobsimison@caixin.com)

Download our app to receive breaking news alerts and read the news on the go.

Get our weekly free Must-Read newsletter.

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR