How Chinese Typewriters Led Way to Predictive Text on Smartphones

How do you represent a language, consisting of tens of thousands of characters, on a single keyboard? Designers of the Chinese typewriter have struggled to fit a vast, non-alphabetic language onto a workable keyboard for over a century, and in the process may have discovered the first clues to advanced text prediction.

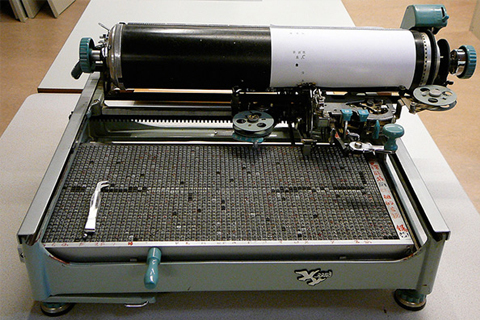

Chinese typewriters have no keys. Instead, the typist moves a lever that allows him to select a letter from a tray full of metal character slugs. When the lever reaches relevant character, the typist presses a bar, and the lever picks up the character, inks it, types it and returns it to its place.

But with over 2,500 characters crammed into a tray, simply finding the correct letter was a daunting task for early typists. And when they rearranged the tray bed to improve their typing speeds, these workers used similar techniques and "anticipation logic" as that used by modern text prediction software, said Thomas Mullaney, an associate professor of Chinese history at Stanford University.

As gadgets evolve, typing has only gotten harder and designers are trying to cram letters onto shrinking surfaces. For example, laptop keyboards are smaller and flatter than the ones attached to desktop computers. Smartphone keyboards force you to type on glass, mostly with your thumbs. And smart watches are so tiny that many have gotten rid of the keyboards altogether. Although our keyboards have shrunk in size, the number of letters, symbols and now emojis users have to type have not, and gadget developers are facing the same dilemma that designers of the Chinese typewriter experienced in the past.

Mullaney started studying the Chinese typewriter in 2008. He stumbled onto the subject after participating in an academic conference on how various fields conceptualize disappearance – archeologists with ruins, for example, or conservationists with extinction. As a historian of China with an interest in language, he pondered the disappearance of certain characters and art of printing and typesetting. "And it dawned on me," he said in a telephone interview, "that I had never seen a Chinese typewriter, so I wondered about it."

Mullaney visited roughly 50 archives in 10 countries, including China, Japan, the United States and in Europe, hunting for early patents of different typewriter designs. Though there have been many studies on language reform, scholars had largely focused on such visible aspects as the simplification of characters, the move to the vernacular and the spread of literacy in the latter half of the 20th century.

Mullaney was more concerned with the less glamorous aspects of language modernization, which he compares to "the plumbing." "So the typewriter, this technological object, is the starting point, but it ventures out into other information technology domains," he said.

The first working Chinese typewriter was invented in the 1880s by a missionary named Devello Z. Sheffield, who spent 44 years in Tongzhou, a district in eastern Beijing. Sheffield wrote many books in Chinese and was good at building things. His obituary in The Milwaukee Sentinel noted that he made "his own electrical machine, which sent off sparks of great size and brilliancy."

To build his typewriter, Sheffield first had to determine how many characters were crucial for the project, so he visited typesetting shops and foundries where movable typeface was cut and forged. "He didn't do a statistical analysis," Mullaney explained, "but he fraternized with Chinese printers and asked for their consult and advice." Sheffield decided to use 4,662 characters that he sub-categorized into 726 very common characters, 1,386 common and 2,550 less common, based on how often they were used, and arranged them in a round tray.

Sheffield's typewriter never became commercially available, but his idea of categorizing characters based on their frequency of usage reappeared in 1910 in the first widely sold typewriter, which was co-developed by Zhou Houkun and Shu Zhendong and manufactured by the Shanghai-based Commercial Press. This typewriter had a rectangular tray that held about 2,500 characters etched into moveable metal slugs and divided into two sections according to the frequency of use. Within each of the two regions, characters were arranged by the Kangxi radical-stroke system used in dictionaries.

Compared to a Western QWERTY keyboard, these machines were bulky and a good typist could only hammer out 20 to 30 characters per minute.

However, in 1951, a typist in Luoyang in the central province of Hubei, named Zhang Jiying was lauded by The People's Daily for typing more than 3,000 characters in an hour, or 50 characters per minute. He later reached a speed of nearly 80 characters per minute. Zhang achieved this speed by rearranging his character tray to include 280 common two-character compounds and several common three and four character sequences – words and phrases like "meidi," or American imperialists; "jiefangjun," or liberation army; and "geming," or revolution. This method quickly caught on, and typists eventually began reorganizing much of their trays according to the words and phrases they expected to use most. It is among the first ever uses of the idea of predictive text found in modern times. Many of these character arrangements were prompted by the ceaseless political campaigns underway in the 1950s and the repetitive and formulaic language used to promote them.

Mullaney says that typists, spurred by Communist politics, anticipated the predictive text that became common in the West only with the advent of the cell phone – an idea so intriguing that Google invited him to share his findings.

The most basic thing that Westerners fail to understand, says Mullaney, is that Chinese computer users "input" rather than "type."

"When I sit down and push a button with a symbol on it, I assume that symbol will appear on the screen," he said. "In China the assumption is the symbols on the keys are not a one-to-one relationship – something happens in between."

The necessity for Chinese computer and cellphone users to create complex systems that effectively turn Latin letters into Chinese characters has made the QWERTY keyboard much more powerful for them, Mullaney argues. "Chinese-language input is now arguably faster than English," he said, because the process of simplifying characters, creating new systems for organizing them and adapting the pinyin phonetic system for transcribing the Putonghua pronunciation have all made it more "keyboard friendly."

"Say I want to develop a system (to input Chinese), the letter 'p' or 'd' can mean anything I want it to do," Mullaney said. "It can be a letter, a sound in a Chinese language, a radical component – many different things."

This has made it possible to input Chinese characters in a computer or mobile device faster than many other languages, he said.

In the West, however, the "alphabetics of the world" have succumbed to "self-congratulation and complacency," said Mullaney, by failing to submit their languages, especially English, to the same sort of rigorous analysis and adaptation to suit the digital age.

There is an "if it ain't broke, don't fix it," attitude that can hinder designers using the Latin alphabet from making new advances in human-computer interaction.

Mullaney is now piecing together the story of how information technology developed in China and how some of the early innovations made here have influenced the way we interact with our devices today.

"The real history of the modern information technology era is nothing like the one we've been told in the hero stories of Bill Gates or Steve Jobs" Mullaney said. "We have a specific story we are constantly telling ourselves and I think that this story, in order to be believed, only works when a quarter of humanity is written out of it. So think about that: For the story to be universal, we leave a quarter of the world out."

Mullaney's goal is to help tell an inclusive tale of the information age – one that has a place for China and all its contributions, starting with the Chinese typewriter.

Sheila Melvin is a newspaper columnist. Her latest book, Beethoven in China: How the Great Composer Became an Icon in the People's Republic, co-authored with Jindong Cai, was published by Penguin Books

A newspaper columnist.

- 1Cover Story: China Carves Out a Narrow Path for Offshore Asset Tokenization

- 2Drownings Shake Chinese Enthusiasm for Travel to Russia

- 3Over Half of China’s Provinces Cut Revenue Targets

- 4Li Ka-Shing’s Port Empire Hit by Forced Takeover Amid Panama Legal Dispute

- 5In Depth: China’s Mutual Fund Industry Faces Overhaul After a Banner 2025

- 1Power To The People: Pintec Serves A Booming Consumer Class

- 2Largest hotel group in Europe accepts UnionPay

- 3UnionPay mobile QuickPass debuts in Hong Kong

- 4UnionPay International launches premium catering privilege U Dining Collection

- 5UnionPay International’s U Plan has covered over 1600 stores overseas