Why Vehicle Sales Have Dipped for the First Time in 28 Years

* Experts disagree on whether government subsidies is a viable way to address decline

* Secretary-general of China Passenger Car Association believes sales momentum will return in 2019 because car ownership in China still lags behind U.S.

At an industry conference in Beijing in early November, a government-affiliated think tank official took to the stage and warned that China’s automobile industry should brace for flat growth in vehicle sales this year.

Just two months ago, the same official, Xu Changming — one of the State Information Center’s four vice presidents — was still upbeat about the country’s overall automobile development. Back then, he said China had sold 28.9 million cars last year, a number he called a far cry from potential annual sales of 42 million.

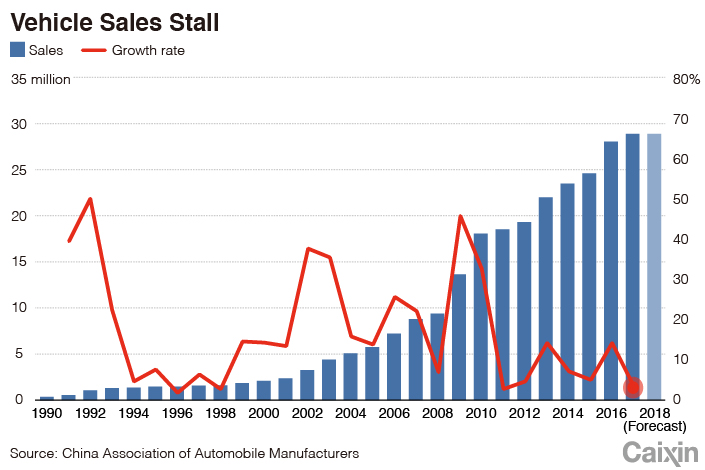

This was the first such remark from the government sector, and the flat growth was mentioned with a positive tone. But concerns started to gather in the industry in October that total sales for 2018 would see a year-on-year decline — the Chinese car industry’s first contraction in 28 years.

In November, Chinese vehicle sales fell 14% year-on-year to 2.55 million, according to figures released by the government-backed China Association of Automobile Manufacturers on Tuesday. For the first 11 months of 2018, sales in the world’s largest car market fell 1.7% to 25.42 million vehicles year-on-year, making an annual decline possible for the first time since 1990.

China’s road to become the world’s largest vehicle market was an astounding one. It surpassed the U.S. in 2009, when car sales surged up 46% from 9.4 million in 2008, thanks to lower purchase taxes, the mandated phaseout of higher-emission vehicles, and the government’s policy of promoting car sales in smaller cities.

Things accelerated for the next five years — total sales doubled to 20 million by 2014 and neared 25 million in 2015. That was when signs of a slowdown emerged. April 2015 brought a year-on-year sales decline in a single month that lasted through September. The market picked up its momentum when the government slashed the purchase tax on low-emissions cars by half.

There are now revived calls for the government to offer subsidies to salvage a looming decline. But not everyone agrees.

“Subsidies are not a panacea. They do not increase demand, but pull the demand to happen earlier,” said Chen Shihua, an assistant secretary-general at the China Association of Automobile Manufacturers.

Why the fall?

The industry is scrambling to work out the reasons behind the sudden decline, and whether the market has what it takes to resume its breakneck growth.

|

China’s car market has been shored up by the rising consumption power of third- and fourth-tier cities thanks to a 2009 policy to promote car sales in such places.

Big cities such as Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen and Guangzhou have capped the number of cars on the road to reduce traffic congestion as migrants flock to bigger cities in search of opportunities. Beijing introduced in 2011 a public lottery to decide eligibility for new car-license plates. Lower-tier cities have no such restrictions.

Third- and fourth-tier cities, which include prefecture- and county-level urban enclaves, make up 59% of China’s gross domestic product (GDP) and 73% of its population. In a 2017 report, brokerage Morgan Stanley estimated that by 2030, the spending power of consumers residing in these cities would reach $9.7 trillion — roughly China’s whole GDP in 2015.

Over the last two years, however, rising property costs and a greater outflow of labor from smaller cities to bigger ones have taken a toll on their overall spending. Half of China’s lower-tier cities saw their home prices rise by at least half in July compared with January 2017, according to Chinese data tracker Wind.

Furthermore, car ownership is no longer a status symbol in China. Consultancy McKinsey & Co. said in a 2016 report that consumers in first-tier cities no longer need to buy new cars: they can lease, rent, purchase used cars, or tap comprehensive online carpooling and ride-hailing services. These emerging services could reduce annual vehicle sales in China by 10% by 2030, the report predicted.

Amid these headwinds, industry-watchers said it would be survival of the fittest.

At the end of 2017, there were more than 250 automakers of all sizes, domestic players or foreign ventures, in China, according to Caixin’s calculations.

Ouster game to begin

“China simply doesn’t need so many automakers; some shouldn’t have existed in the first place,” said Gong Min, an auto-market analyst at UBS Investment Research. Gong said foreign players are expected to take a greater hit than local automakers because the latter remain shielded by local governments.

“Foreign brands come to China to make a profit. If the local conditions turn sour, they can just dispose of their assets and leave,” Gong said.

Japanese automaker Suzuki Motor Corp. has been one of the first casualties.

It announced in September it will retreat from the Chinese market after 25 years, saying its more-compact, lower-end car models were less competitive now that Chinese consumers prefer sport and utility vehicles. Suzuki’s state-run joint venture partner, Chongqing Changan Automobile Co. Ltd., will take over the company’s half-share in the venture and carry on building Suzuki-branded cars.

The Chinese market can’t support more than 10 major automakers in the long haul, experts and industry executives said at a Beijing auto show held in April.

Despite the grim prognosis, one industry association claims hope is not lost.

Cui Dongshu, secretary-general of the China Passenger Car Association, told Caixin he expected the bumps to be temporary. As car ownership in China still trails that of the U.S., the momentum will start to pick up next year, albeit at a smaller scale, he predicted.

Tang Ziyi contributed to this report.

Contact reporter Jason Tan (jasontan@caixin.com)

- 1Cover Story: China Carves Out a Narrow Path for Offshore Asset Tokenization

- 2Drownings Shake Chinese Enthusiasm for Travel to Russia

- 3Over Half of China’s Provinces Cut Revenue Targets

- 4Li Ka-Shing’s Port Empire Hit by Forced Takeover Amid Panama Legal Dispute

- 5In Depth: China’s Mutual Fund Industry Faces Overhaul After a Banner 2025

- 1Power To The People: Pintec Serves A Booming Consumer Class

- 2Largest hotel group in Europe accepts UnionPay

- 3UnionPay mobile QuickPass debuts in Hong Kong

- 4UnionPay International launches premium catering privilege U Dining Collection

- 5UnionPay International’s U Plan has covered over 1600 stores overseas