In Depth: How Wuhan Lost Its Grip on Thousands of Suspected Coronavirus Cases

|

Editor’s note: This is the fourth part of Caixin’s exclusive four-part in-depth report on China’s fight against the coronavirus outbreak. Please click here to check out part one, part two and part three.

(Wuhan) — On Jan. 22, Li Yunhua looked at 266 CT scans from patients with fevers. Around half showed a similar kind of lung infection.

The radiologist at Wuhan’s Hubei Xinhua Hospital looked through the scans, counting them with trembling hands, and sat silently for a long time. Very few of the reports mentioned the new coronavirus, but he knew it was the cause. The next day, the city’s government would put the city on lockdown, severing its public transportation links with the rest of the country.

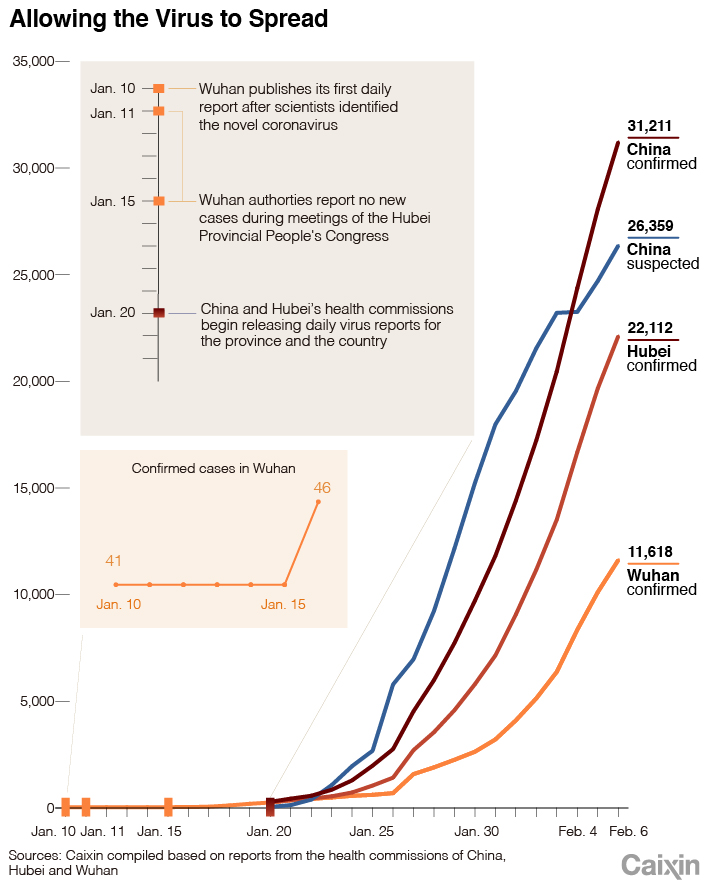

In the weeks since, the virus shown on the scans has engulfed the central Chinese city and its 14 million residents. As of Friday, Wuhan has 11,618 confirmed cases and 478 deaths, by far the highest tally in China.

Also on Jan. 22, an anxious man queuing on behalf of his father at the Wuhan Red Cross Hospital told Caixin that he wanted to know if his father’s was ill because of the coronavirus. “I wish my dad could take the test and get a clear answer. But the hospital said they don’t have the detection kit for it. They can’t confirm his case.”

The man, surnamed Wu, said his father’s home was three kilometers (1.8 miles) from the South China Seafood Market, the suspected point of origin for the coronavirus outbreak, and he would cycle past it every day on his way to work as a chef.

On Jan. 13, Wu’s father came down with a fever. After three days on an IV drip at a community clinic his fever subsided. However, its return on Jan. 19 led him to head to a hospital, where he was told no problem could be found. On Jan. 21 his fever rose to 38 degrees Celsius and the following day he went for a CT scan in the Red Cross Hospital — which found a severe lung infection. Though the doctor said he should be hospitalized, there were no beds available and he had to return home, still without a coronavirus diagnosis one way or the other.

“There are no places available,” Wu said. “He will come here for an IV, return home, and come again tomorrow.”

People like Wu’s father are everywhere in Wuhan. Caixin learned of dozens of people who have been unable to find out whether or not their illness is the novel coronavirus and have not been quarantined. Even medical staff showing symptoms struggled to have it confirmed. Multiple frontline medical workers told Caixin that there were probably over 10,000 suspected cases in the city before Jan. 22.

Questions remain over how closely the official numbers reflect reality, why patients are not being diagnosed promptly and what happens when they slip between the cracks. The slow pace of coronavirus diagnosis, driven both by stringent diagnosis criteria and bottlenecks in testing methods, has especially stymied disease control efforts, as many suspected cases were simply sent home, often to infect their families and those around them.

|

How many ‘suspected’?

Health authorities now classify coronavirus patients into one of four categories: confirmed patients, suspected cases, those suffering fevers and those who had intimate contact with an infected person.

For a while, however, almost all suspected cases were given the vague diagnosis of “viral pneumonia.” Some doctors were ordered not to use the word “viral” and instead simply diagnose people with pneumonia more broadly.

“Some patients only have mild symptoms, but if they are not quarantined, the infection is hard to control,” said Guo Yabin, the associate director of the Infectious Disease Department at Guangzhou’s Nanfang Hospital, who played a role in the fight against SARS. However, the novel coronavirus is harder to identify and control than SARS, which killed hundreds in 2003.

A 64-year-old resident of Wuhan’s Qingshan district who was running a high fever received a CT scan on Jan. 17 that showed both his lungs had infections. He neither received a coronavirus diagnosis nor was hospitalized, due to the lack of beds, so he returned home. His wife later became sick.

An 82-year-old in the neighboring district of Jiang’an died with a high fever on the evening of Jan. 25. The head of his community committee told Caixin that it was the second death in that residential community since 17 of its residents had been identified as “suspected” coronavirus cases.

Since the lockdown began, the city’s hospitals have been completely swamped by patients, confirmed and suspected, with both severe and mild symptoms. Hospitals have had to establish makeshift fever clinics inside small community clinics without the necessary equipment to identify whether feverish, coughing patients are suffering from the novel coronavirus or a common cold. Many patients who had been feverish for days, and had been identified as being “highly suspected” coronavirus cases, would be sent home. Some received tests for the coronavirus only when their condition declined to the point they had to be sent to an intensive care unit (ICU) in Wuhan, according to Xi Xiuming, an ICU doctor at Beijng’s Fuxing Hospital who has been deployed in Wuhan.

|

A crowd of patients surround a hospital worker inside an outpatient fever-treatment clinic at Wuhan Red Cross Hospital on Jan. 22. Photo: Caixin |

Xi told Caixin that it’s hard to understand how the virus is now spreading by only looking at the official infection numbers, as they don’t say whether the new confirmed cases every day are from people who have just begun showing symptoms or from people who have already been labeled as suspected by the medical authorities for several days.

“We need to know, first of all, how many patients are in the fever clinics every day, and how many of the feverish are suspected of having the new coronavirus. Second, we need to ask, what’s the demographics of the fever patients? Is the number of people with fevers rising or declining from day to day? We also need to know how many suspected patients end up hospitalized and how many are removed from the suspected list,” Xi said.

Ultimately, the ambiguity of the numbers shows that management of this crisis has been chaotic, Xi said.

For a long time, the local government was silent on the number of suspected patients. It wasn’t until the city had been shut down for three days, on Jan. 26, that Mayor Zhou Xianwang gave a figure for “suspected” cases — saying that as of Jan. 25, 2,209 hospitalized patients were suspected but not yet confirmed.

However the authorities didn’t say how many non-hospitalized suspected cases there were.

Read More

In Depth: How Wuhan Lost the Fight to Contain the Coronavirus

In Depth: How the WHO’s Global Health Emergency Decision Unfolded

In Depth: Tracing the Coronavirus’s Origins

Slow reactions

The authority’s difficulty in dealing with suspected cases was not only due to a lack of hospital and quarantine beds, but also one of diagnosis.

Moreover, Wuhan ICU doctor Peng Zhiyong told Caixin that in mid-January the diagnosis criteria for coronavirus set by the city’s health commission were too stringent and that his hospital repeatedly told the authorities that these criteria would lead to very few diagnoses. To be confirmed, a patient would have to have had exposure to the wet market where the virus is thought to have originated, have a fever and test positive for the virus. It wasn’t until two teams from the national health commission visited the city that the criteria were changed and the number of confirmed cases rose quickly.

At first, only the national health authorities could give someone a test for the virus. According to Zhao Lei, who works at the infectious disease department of Wuhan Union Hospital, gene sequencing at the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention’s Beijing headquarters was the only way to test for the virus before Jan. 18, but this would take three to five days.

However from Jan. 18, the Hubei provincial branch began performing nucleic acid tests to confirm if a patient had the novel coronavirus. However, it was a winding road to get a case in front of the Hubei CDC. The local health authorities decided that several tests, including a CT scan, must first be conducted. Then the case should be transferred from a district disease control center, then to the city-level center and finally to the provincial level before it could be officially confirmed. This bureaucratic procedure, combined with the city’s health system being overwhelmed, meant that many suspected cases slipped through the cracks.

|

Patients spill out into a hallway at Wuhan Red Cross Hospital as they wait for diagnosis and treatment on Jan. 22. Photo: Caixin |

Moreover, according to Wuhan’s Party Secretary Ma Guoqiang, speaking at a press conference on Jan. 28, the Hubei CDC’s testing capacity was only around 200 to 300 tests per day. At the time, over 5,000 fever patients were seeking treatment and diagnosis at the city’s medical facilities each day.

Now up to 30 Chinese pharmaceutical firms have started producing coronavirus testing kits. Once at full capacity, it’s estimated that together they will be able to make up to 600,000 testing kits a day. Still, on Feb. 3, medical experts admitted on national television that not everyone in Wuhan who needs a test can access one, and called on the entire nation to help increase testing capacity.

Another bottleneck, the lack of hospital beds, shows signs of easing, too.

The guidelines on dealing with the outbreak issued by the national CDC have been revised repeatedly in the last two weeks. The latest guidelines say that any suspected patient should be quarantined in a hospital isolation ward, though even as the city races to construct isolation facilities, there isn’t the capacity to properly house all suspected patients, let alone those who have been in contact with them such as their relatives.

In the first batch of hospitals designated for the coronavirus, there were only about 800 beds. On Jan. 21, the authorities announced they were making another 1,200 beds available, and a few days later announced further measures including the construction of two new hospitals from scratch for confirmed patients. By the end of the month, over 10,000 beds had been given over to coronavirus patients, though most of the measures were taken after the city was locked down on Jan. 23.

Over the past few days before publication time, Wuhan has begun to set aside large public spaces such as gymnasiums and exhibition centers to quarantine patients with mild symptoms away from home. The Wuhan government was ordered to hospitalize all confirmed patients by the end of Wednesday.

Zhao Lei, the doctor who dealt with the “super-spreader” that infected over a dozen medical staff at Union Hospital, said the lesson should be that prevention rather than containment is key when fighting a contagious disease.

“Prevention should be the priority in disease control, especially for infectious disease. It’s no longer just experience passed down from our successors. It is now a hard learnt lesson,” Zhao said. “Otherwise, no matter how much money and energy you sacrifice afterward to deal with it, the losses made are hard to recoup.”

However it remains difficult to know how many people are really infected. Many likely cases are still out of sight, sitting at home in a locked-down city or still waiting for a bed in the city’s hospitals. Even as the city begins to get a grip on the crisis, there is no end in sight to its struggle with the novel coronavirus.

He Xin, Chen Baocheng, Tang Ailin, Wang Su, Yang Rui, Zhang Yang, Huang Yuxin contributed to this report.

Contact reporter Isabelle Li (liyi@caixin.com) and editor Joshua Dummer (joshuadummer@caixin.com)

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR