Cover Story: The Accelerated Push for a Nationwide Property Tax

China is accelerating long-discussed plans to roll out a nationwide property tax. Experts say such a tax could be tested by the end of this year in some first- and second-tier cities that have hot real estate markets, most likely Shenzhen and the southern island province Hainan.

The central government for years has been mulling a tax on homeownership, and Shanghai and the southwestern megacity of Chongqing were chosen in 2011 to conduct trials of levying taxes on certain houses. Since then there has been much discussion of expanding the tests nationwide, though there has been little progress in a decade.

Local governments have been reluctant to push for such a tax out of concern that it will cause property values to fall and dampen demand for land, hurting a major source of their fiscal revenue. Experts argue that won’t be an issue.

On May 12, officials of the Ministry of Finance, the Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, the State Taxation Administration, and the national legislature’s budgetary affairs commission held a seminar to solicit opinions from experts and local government officials on pilot-testing property taxes, according to an official statement.

Test first before legislation

The brief statement sent a signal different from previous official remarks. The government in the past always talked about property tax legislation and reform, but this time the wording changed to “pilot testing property tax reform.” Some experts interpreted the change as a sign that the government aims to give property taxes a trial before passing legislation.

“Although legislators have been drafting property tax legislation for many years, a draft needs to solicit comments and be deliberated by the National People’s Congress,” said Shi Zhengwen, a professor specializing in tax law at the China University of Political Science and Law. “Generally, a new law will be reviewed three times, so it will take at least one or two years.”

Caixin learned that lawmakers drafted property tax legislation in 2018 and have been soliciting comments from local governments and relevant ministries, but it has not yet been submitted to the National People’s Congress (NPC) for deliberation.

The draft law is being completed and will be filed for preliminary review by legislators “when conditions are ripe,” Wu Ritu, vice chairperson of the Legislative Affairs Commission of the NPC, said in March 2019. Since then no update has been made.

It appears the authorities intend to launch a pilot run before issuing a new law as the legislative process has encountered some difficulties, said Liu Yi, a Peking University professor specializing in fiscal policy.

Shi said he expects a pilot program to be launched this year in a few cities. Several experts said the pilot cities must be representative of first- and second-tier cities. Among the first-tier cities, Shenzhen is most likely to be chosen as a pilot city, and other possible choices may be some second-tier cities with good economic levels and hot housing markets, said Ma Guangyuan, an economist and property issues commentator.

Jia Kang, chief economist of the Huaxia New Supply Economics Research Institute, called for pilot testing property taxes in Shenzhen and Hainan. Shenzhen, as the pioneer demonstration zone for China’s reform and opening-up, and Hainan, with the world’s largest free trade port zone, have been given greater autonomy for restructuring, making them suitable choices for testing property taxes, experts said.

|

Conducting a pilot program can also help accelerate legislation by addressing problems that may occur after the new tax is officially launched, Shi said.

Although there are still different opinions on the order of legislation and pilot programs, many researchers say they believe property tax legislation should be completed by 2025 during the 14th Five-Year Plan.

Long-term tool for local governments

The central government needs long-term measures to regulate the real estate market. A property tax, which would combine legal and economic measures, could be a good long-term tool with multiple functions such as complementing the local fiscal and taxation system, improving government and national governance and adjusting income distribution, Shi said.

China’s home prices grew at the fastest pace in eight months in April after curbs failed to stem buyer enthusiasm. New home prices in 70 cities, excluding state-subsidized housing, rose 0.48% last month from March, when they gained 0.41%, National Bureau of Statistics figures showed Monday.

Rising housing prices are prompting China to speed up the launch of property taxes, but it’s not the main reason. Because the new tax will increase the cost of owning property, it’s a common belief that it would discourage speculation and serve to constrain housing prices.

However, the trials in Chongqing and Shanghai have shown that property taxes have had limited impact on real estate prices. The same has been true in other countries that have introduced real estate taxes. Beijing has downplayed that narrative since 2010.

There are two main factors affecting housing prices: land supply and monetary policy. With or without a property tax, the impact is minimal compared with the two main factors, said Chinese property development tycoon Pan Shiyi.

Experts including Shi told Caixin that the introduction of property taxes may dampen housing prices in the short term, but in the long term, it is not intended to regulate housing prices.

|

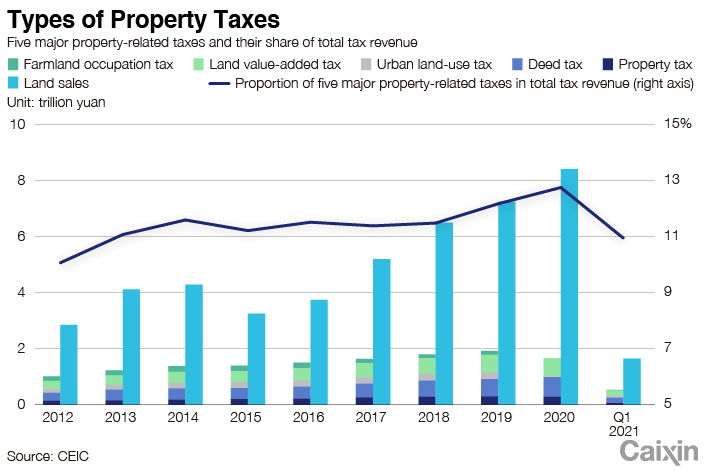

The main purpose of such a tax is to provide a stable source of income for local governments. An overhaul of the tax revenue distribution system in 1994 diverted the lion’s share of the country’s fiscal revenue from the regional and local governments to the central government. For instance, 45% of China’s fiscal revenue last year was handed over to the central government, up sharply from 22% in 1993. Amid weak growth of tax revenues, some local governments heavily rely on the sale of land-use rights to cover costs such as infrastructure and social welfare programs.

The country’s recent tax cuts to help support the economic recovery have further damaged local governments’ finances. Data from the Ministry of Finance show that fiscal revenue declined 3.9% in 2020, and tax revenue declined 2.3%.

Legal foundation for property tax

Opponents of property taxes also question the rationality of levying tax on houses built on land that home buyers don’t even own.

Up until the early 1990s, most urban homes were owned by the state and provided through work units, but the government started to privatize public housing and encourage private real estate development to boost the economy. Homeowners in China own their dwellings but not the land under them. All land in China is owned by the government, which sells land-use rights to developers and homeowners through 20- to 70-year leases.

“It is an important legal doctrine that wealth taxes must not be imposed on state-owned land,” said Xu Shanda, a former deputy head of the State Taxation Administration. “Even though Chinese property owners own the building, the land is owned by the state.”

But Liu Jianwen, a law professor at Peking University specializing in tax and the economy, contends that this legal obstacle was removed when the Property Law came into effect in 2007. The law defined rights to the use of land for construction purposes in a way that is “almost equivalent to ownership rights,” he said.

Internationally, there are also many examples of countries levying property tax on houses built on publicly owned lands. Countries including Singapore, Israel and Australia have coordinated the relationship between public land-use rights and house ownership within their legal framework.

Even though China doesn’t have a nationwide property tax, there are many types of taxes levied on real estate development and transactions, including farmland occupation tax, urban land-use tax, land value-added tax, deed tax, corporate income tax, personal income tax, and stamp duty. There have long been arguments that the tax burden during the construction and transaction process is too heavy, while taxes in the possession stage are too light.

Proceeds from land and property-related taxes amounted to 1.96 trillion yuan ($305 billion) last year, or about 20% of local governments’ annual income, according to Ministry of Finance data.

Former Finance Minister Xiao Jie suggested that as a new property tax is levied, the tax burden during the construction and transaction process should be reduced accordingly.

Some experts suggested eliminating the land value-added tax. In place since 1994, the land value-added tax was created in the aftermath of the real estate bubble in the early 1990s.

The tax is imposed on developers at progressive rates ranging from 30% to 60%, depending on the amount of value appreciation on the transferor of land-use rights. The tax is usually passed on by developers to home buyers.

No matter when and in what way the property tax is levied, what is certain is that the new tax will affect land-use sales by local governments, according to a report by brokerage Guotai Junan. In the past, local governments usually adjusted the supply of land according to market demand. Once the property tax is implemented, local governments will be motivated to sell more land-use rights to collect more property tax in the future, the report found.

Contact reporter Denise Jia (huijuanjia@caixin.com) and editor Bob Simison (bobsimison@caixin.com)

Download our app to receive breaking news alerts and read the news on the go.

Get our weekly free Must-Read newsletter.

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR