Update: It’s Banks’ Turn for the Hot Seat of Supply-Side Reform

Three years after China started a supercharged regulatory storm to dismantle a labyrinthine web of shadow banking activities and lower the country’s debt ratio, the winds are abating as policymakers shift their focus to supporting the economy.

Signs are increasing that the deleveraging campaign has yielded ground to a more pressing structural problem — how to change the financial system so that more credit is channeled to activities that produce real goods and services and to underserved sectors of the economy such as small and private companies.

Officials have recently been declaring that they have achieved initial success in their efforts to curb financial risk and in their goal of structural deleveraging, and President Xi Jinping last month called for deepening supply-side structural reform in the financial sector, setting the tone for regulatory policymaking this year and underscoring the change in focus.

Supply-side structural reform has been a key feature of the economic landscape since late 2015 when Xi first referred to the initiative during a high-level economic policymaking meeting. The strategy initially focused on five components: cutting industrial overcapacity, reducing leverage in the corporate sector, cutting the stock of unsold homes, bringing down taxes and fees for companies, and addressing “weak links” in the economy. But it has now zoomed in on the financial sector after Xi’s call, which came at a Feb. 22 meeting of the Politburo, a committee of the Communist Party’s 25 most-senior members.

The announcement is a clear sign that the government’s drive to reduce risks, the top priority of the “three tough battles” that Xi has vowed to win by 2020, has entered a new phase, said Zhao Jian, chief economist of Atlantis Investment Management, a Hong Kong-based investment services provider focused on China.

“The (government’s) thinking in the past focused on destroying (old practices), hoping that strengthened regulation would not only destroy but also create something new,” Zhao said. “However, the reality has not turned out that way — we’ve had the destruction without the creation, and the private sector has been the victim. Now it’s time not just to destroy but also to create.”

Diversify credit risks

One of the key concerns of policymakers is the concentration of financial risk in the banking system, which stems from an over-reliance on indirect financing, mostly via banks, to supply the water that irrigates economic activity. In developed economies such as the U.S. and the U.K., bank lending, the dominant form of what’s known as indirect financing, plays a much smaller role than direct financing, where businesses raise funds straight from investors through channels such as equity and bond sales.

But in China, indirect financing dominates — direct financing made up less than 18% of outstanding total social financing, China’s broadest measure of credit, in 2018, according to Caixin’s calculation based on data from the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), underscoring the economy’s excessive dependence on bank lending.

The dominance of bank lending stems partly from the legacy of China’s planned economy, but in a market-based economy increasingly driven by the private sector, it has serious shortcomings. Banks have traditionally favored state-owned enterprises (SOEs), whose debts are implicitly backed by the government, and property developers, who can put up higher collateral. Small and privately owned firms, the lifeblood of the economy, have been underserved partly because they can’t put up the required collateral and partly because, in the absence of a fully functioning credit reference system, banks have found it hard to assess how risky lending to them would be.

As a result, huge amounts of credit have been directed to debt-laden, money-losing SOEs, known as “zombie” companies, and to the property sector, fueling bubbles in the housing market. Private companies have been forced to turn elsewhere for financing, usually to shadow banks that charge far higher interest rates.

Government data show that private companies account for half of China’s tax revenue, 60% of gross domestic product and 80% of urban employment. But according to Guo Shuqing, chairman of the China Banking and Insurance Regulatory (CBIRC), they only account for about 25% of bank lending.

Pan Gongsheng, a deputy governor of the PBOC and head of the State Administration of Foreign Exchange, criticized “structural flaws in the supply of financial services” when asked about the purpose of the financial supply-side structural reform in an interview with the Financial News, a publication run by the central bank. The quality and efficiency of the allocation of financial resources have “lagged behind the requirements needed for high-quality economic development,” he said.

“Equity financing is severely underdeveloped,” he said in the interview published late last month. As one of the main tasks of the reform, Pan listed the building of a “multi-level capital market” to broaden companies’ access to equity financing.

|

Equity financing

Exactly what “multi-level capital market” means has yet to be clarified by policymakers. But Guo said on March 5 that such a market should accommodate both large securities bourses and regional equity exchanges and involve institutions such as private equity funds and venture capital firms that are strong in investing in high-risk but innovative companies.

The launch of the Nasdaq-style high-tech board in Shanghai, which was proposed by Xi in November, will be the top priority of financial supply-side structural reform in the capital market this year, Yan Qingming, a vice chairman of the China Securities Regulatory Commission, told reporters (link in Chinese) in early March.

The Sci-Tech Innovation Board, to use its official title, aims to make it much easier for technology startups to tap the stock market for funding. Pre-profit and pre-revenue companies, as well as firms with special ownership arrangements such as dual-class share structures — all of which are currently excluded from China’s main boards — will be accepted by the high-tech board as long as they meet certain criteria.

Guo of the CBIRC has said the main thrust of financial supply-side structural reform will be to meet the financing needs of small and privately owned businesses.

“Appropriately solving the problem of how to provide lending, credit and financial support to small enterprises and private companies is the most important part of financial supply-side structural reform,” Guo told reporters on March 5 on the sidelines of the National People’s Congress (NPC).

Outstanding loans extended to companies with access to loans of up to 10 million yuan ($1.49 million) accounted for less than 7% of total bank lending at the end of 2018, or 9.36 trillion yuan, according to CBIRC data. Even so, that was a 21.79% jump from 2017 as banks rushed to lend to small companies to meet regulatory requirements. The average interest rate on new loans granted to those companies in the fourth quarter was 7.02%, down from 7.82% in the first quarter.

Guo has previously warned that annualized interest rates on loans from alternative institutions such as microlending firms, pawn shops, and private equity funds could be as high as 30%, raising the chances of default.

Help wanted

As well intentioned as it was, the deleveraging campaign had the unintended consequence of hitting private sector companies disproportionately hard as the shadow banking channels they depended on were the worst affected by the policy. Amid a squeeze on shadow-banking activities, companies found it increasingly difficult to refinance their debt, which led to a wave of defaults that roiled the stock and bond markets, triggering an unprecedented government-backed rescue for private companies.

In the annual government work report issued on March 5, Premier Li Keqiang vowed to increase loans by large state-owned banks to small enterprises by more than 30% this year, as part of efforts to ease the credit crunch and bring down their overall financing costs.

Policymakers are seeking to use financial supply-side structural reform to provide aid to small and private firms in a more regular and sustainable way by opening up the financial markets to smaller players and reduce the dominance of large state-owned banks and insurance companies.

The reform aims to build a network of diversified financial institutions that offer products tailored to the needs of different sectors in the economy, Xiao Yuanqi, the CBIRC’s chief risk officer, told reporters at a briefing on Feb. 28. It will push for the greater presence of smaller players and more specialized organizations such as wealth and asset management companies and investment firms, and open the industry up further to foreign investors to increase competition, he said.

Financial institutions will be encouraged to accept more types of assets as collateral, such as patents and other intellectual property rights, rather than just physical assets such as equipment and property when they grant loans, Xiao said.

The CBIRC intends to gradually reduce and even cut off credit supply to industries suffering from excess capacity and to “zombie” companies, thereby unlocking more funds to support the growth of innovative and strategic sectors and small businesses.

Bank overhaul

But it remains a daunting task for banks to recover funds from deadbeat firms partly because of the slow progress in overhauling the SOE sector and intervention by local governments, who rely on the companies to provide jobs.

Banks will also have to undertake some overhauls of their own. Pan from the PBOC said Chinese banks still lack sound internal governance and technological know-how, which he suggested undermine their ability to lend and invest efficiently. Financial supply-side structural reform will look to reshape the business models, risk management and performance assessment mechanisms of financial institutions, he said.

China has more than 4,000 banks, including at least 169 commercial banks and thousands of rural lenders, many of which are struggling as their balance sheets have been weakened by mountains of bad debts.

Guiyang Rural Commercial Bank, in southwest China, one of the country’s poorest regions, is just one example of dozens of banks that are in trouble. Its nonperforming loan ratio surged to 19.54% at the end of 2017 from 2.93% in 2015, figures revealed by a ratings agency showed. Its core Tier-1 capital adequacy ratio, a key measure of financial strength, has turned negative, indicating it has no ability to absorb losses on bad debts.

The government has so far been reluctant to let banks go under, however, due to fears that such failures may sap the public’s confidence in the banking system and undermine social stability. But financial supply-side structural reform may finally allow that to happen. Officials including Xiao from the CBIRC and Wang Jingwu, the head of the PBOC’s financial stability bureau, have said the authorities may trial bankruptcy of a few individual banks, although they will still seek to rescue most failing banks through mergers and restructuring.

Contact reporter Fran Wang (fangwang@caixin.com)

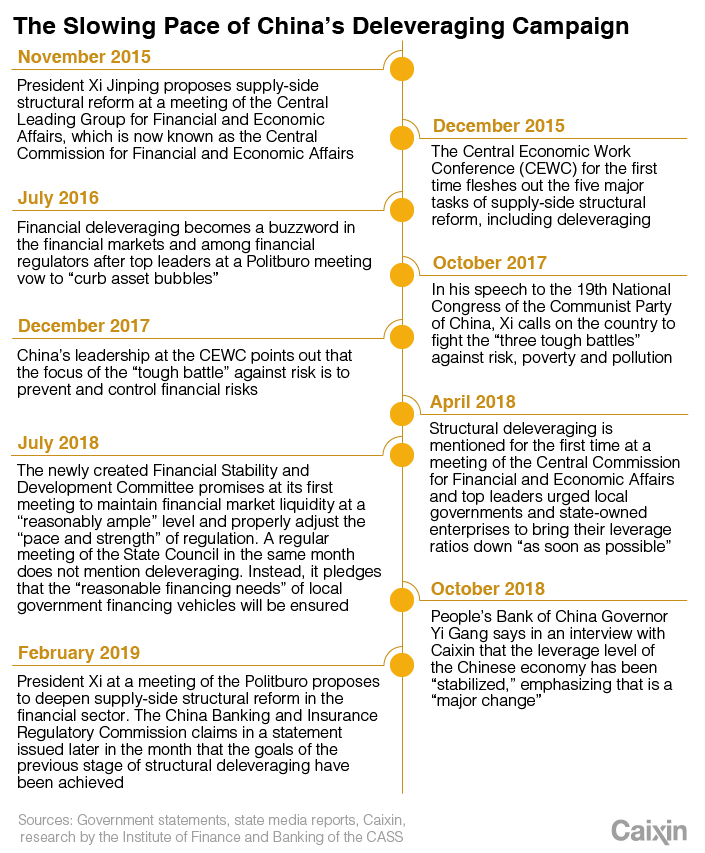

This article has been updated with a timeline about the slowing pace of China's deleveraging campaign.

- 1Cover Story: China Carves Out a Narrow Path for Offshore Asset Tokenization

- 2Drownings Shake Chinese Enthusiasm for Travel to Russia

- 3Over Half of China’s Provinces Cut Revenue Targets

- 4Li Ka-Shing’s Port Empire Hit by Forced Takeover Amid Panama Legal Dispute

- 5In Depth: China’s Mutual Fund Industry Faces Overhaul After a Banner 2025

- 1Power To The People: Pintec Serves A Booming Consumer Class

- 2Largest hotel group in Europe accepts UnionPay

- 3UnionPay mobile QuickPass debuts in Hong Kong

- 4UnionPay International launches premium catering privilege U Dining Collection

- 5UnionPay International’s U Plan has covered over 1600 stores overseas