Slumping Stocks Stoke Fears of Pledged-Share Meltdown

* Regulatory overhaul, a shadow-banking crackdown and a slumping stock market have overwhelmed shareholders who pledged stock to obtain loans

* Recent stock market slump has piled even more stress on shareholders who pledged their holdings as collateral

(Beijing) — Shareholders and directors of Chinese listed companies have for years used their stakes as collateral for loans. So when a metal-products maker in southern China wanted to buy a European business 18 months ago, Chairman Cheng Gexin (not his real name) decided that rather than wait for a bank loan, he would raise the 200 million yuan ($30.0 million) he needed more quickly by pledging part of his stake in the Shenzhen-listed manufacturer to a brokerage firm.

He could then take more time to get a bank loan and use that money to buy back his pledged shares in the company, which is listed on the ChiNext, a Nasdaq-style board for growth companies.

Except the loan never came through, leaving Cheng unable to buy back his shares. As he struggled to raise the money, the company’s stock price started falling, and the broker demanded he pledge additional shares to compensate for the drop and safeguard its loan. The chairman was also facing a demand for more shares to meet margin calls on another pledged-stock loan from another securities firm as the drop in the ChiNext in the first two months of this year pushed the company’s share price down by another 20%.

By the time the shares were suspended in mid-February, pending an announcement of a new share offering to fund an acquisition, Cheng had pledged 80% of his entire holding in the company. Almost half of the loans were nearly due to be paid back before the suspension or their repayment has been deterred, and fortunately for Cheng, the shares were frozen just above the price that would have entitled his brokers to sell his pledged stock.

The stock suspension gave the chairman some breathing room, but with other funding channels also drying up as a result of the government’s campaigns to rein in “shadow banking” and the asset management industry, he was struggling to refinance his debts.

Perfect storm

“We’re getting demands from people who want their money back almost every day –– they are driving us to the wall,” Lillian Wang, the company’s general manager and Cheng’s business partner of 20 years, told Caixin last month as she sat in her office anxiously checking the stock market’s performance on her computer screen.

Cheng and Wang are caught up in a perfect storm of a regulatory overhaul, a shadow-banking crackdown, and a slumping stock market. The assault has overwhelmed shareholders who pledged stock to obtain loans, threatening to wrench their businesses from their control and force massive losses on other investors as share prices plunge amid dumping by brokerages and other creditors.

“Recently I’ve been dealing with these risks (from pledged shares) every day, I’m overloaded with work,” a manager of the securities pledging business of a brokerage firm told Caixin.

The stock market rout in the summer of 2015 triggered a wave of regulations by the government aimed at reducing the risks of another confidence-shaking slump. The practice of pledging shares was curtailed after the market collapse, and more restrictions were piled on in 2017 and early 2018.

One of the aims of the regulations was to restrain major shareholders, especially those of smaller companies, from obtaining loans for personal spending needs, boosting short-term company cash flow, or for speculative activities such as lending in the shadow-banking market. As a result, a large pool of liquidity previously available to smaller companies shunned by the formal banking system began to shrink, making it more difficult and costly for them to refinance their debt.

|

“The abrupt change in the policy environment was devastating — (brokers) told me all of a sudden that they would not continue lending,” said Cheng from the metal manufacturer. Starting in mid-February, his brokers refused to extend the repayment date of several maturing stock-backed loans, and no securities houses would grant new lending against the remainder of his holdings.

Asset management crackdown

There was more bad news from the regulatory overhaul of the $16 trillion asset management industry. New rules originally unveiled in October and implemented in late April led commercial banks to scale back their sales of wealth management products (WMPs) and trust companies pulled back from the “channeling business,” which involves the sale of high-yield trust products to banks, companies and high-net-worth individuals. Such products often took the form of high-interest loans to smaller companies that were ineligible to borrow from banks.

The squeeze led to a dramatic decline in money flowing into financial activities and into companies, including brokerages whose loans involving pledged shares were often funded through WMPs and trust products. It also directly reduced funds available in the over-the-counter (OTC) market for share pledging, where banks and trusts are the main lenders, and deals do not go through the stock exchanges.

“The supply of funds in the market has been decreasing, so securities firms are raising the bar (for share-backed loans) as they become more cautious about the business,” a source with a Shanghai brokerage, who declined to be identified, told Caixin.

The recent stock market slump has piled even more stress on shareholders who pledged their holdings as collateral for loans.

China was one of the world’s worst performing markets in the first half — the benchmark Shanghai Composite Index dropped 14% and sank below the key psychological support level of 3,000 on June 19 for the first time in nine months.

The decline risks creating a vicious cycle of forced stock sales as falling prices trigger margin calls that compel borrowers to cough up more shares as collateral for their loans. Those who cannot do so and fail to repay their loans face the prospect of brokerages selling the pledged shares into the market, further depressing prices.

Citic Securities, for example, has since early June made seven large sales of shares in Spearhead IMC Group, a ChiNext-listed digital marketing company, amounting to 1.07% of its outstanding equity. The disposals were made after Shanghai HuanXin Investment Consulting Co. Ltd. missed margin calls on Spearhead shares it had pledged to the brokerage in return for loans. Shanghai Huanxin is jointly owned by two of Spearhead IMC’s vice presidents and a board director.

On June 15, Citic Securities also dumped more than 5.6 million shares of Shenzhen-listed financial services firm Meson Fintech Co. Ltd. The stock, which was pledged by an individual investor, accounted for 1% of the company’s outstanding shares and 12.5% of the turnover of the company’s shares that day.

‘Liquidation line’

The sell-offs have fanned concerns of a repeat of the 2015 stock market rout, which was exacerbated by forced disposals triggered by a crackdown on margin trading to curb credit-fueled stock speculation.

Since late May, the share prices of at least 30 companies have collapsed to the level that would allow brokerages to dump stock pledged by their major shareholders for loans, known as the “liquidation line,” according to Caixin calculations based on the firms’ stock exchange filings.

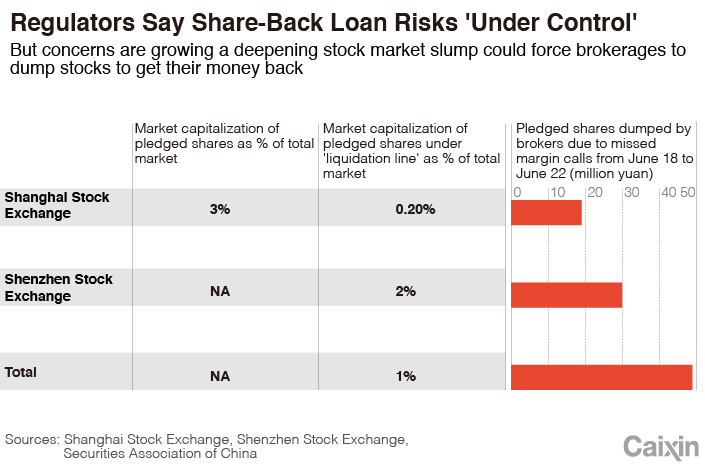

The value of shares below the liquidation line accounted for 1% of the combined market cap of all China-listed firms, figures released on June 26 by government-linked industry group Securities Association of China showed. That means the value of stocks in danger of being liquidated was around 500 billion yuan based on the total market capitalization of the country’s two stock markets at the time. Counting deals made via the OTC market, the total value of pledged stocks facing liquidation would more than double to surpass 1 trillion yuan, according to some industry insiders.

Executives of several lenders told Caixin that the value of pledged securities hitting the liquidation line as a percentage of all stocks they held as collateral has reached a record high.

“About 5% of our (share-backed lending) business is in danger of going wrong,” a source with a securities firm in Shanghai, who spoke on condition of anonymity, told Caixin. “The rate could be higher, possibly more than 10%, at brokerage houses that were more aggressive” in expanding in the business.

The situation is deteriorating rapidly at his firm, with the number of stocks hitting the liquidation line more than doubling since the end of April, he said.

Even so, only 49 million yuan worth of pledged shares were sold via the Shanghai and Shenzhen stock exchanges over one week in mid-June, according to bourse data, a fraction of the estimated value of securities under the liquidation line. This suggests that actual dumping of shares has been fairly small so far.

But authorities have become concerned, and in an effort to calm the markets, several financial regulatory bodies took concerted action late last month, issuing statements that risks in the share-backed loan market were “generally under control.”

‘Fatal blow’

Banks and trust firms have been discouraged from selling pledged shares in the OTC market. The two bourses have also increased window guidance on the sale of pledged shares by securities firms, requiring them to negotiate with the borrower before proceeding, multiple sources told Caixin.

“The window guidance emphasizes that stability must be maintained,” the executive with the Shanghai broker said. “Regulators are concerned about the impact of liquidation on stock prices.”

Some securities companies were ordered on June 26 to not sell more than 5 million pledged shares in any one company, according to one source working for a brokerage who declined to be identified.

Wang described the government’s policy tightening of control over pledged shares as a “fatal blow” to her company. Chairman Cheng was reluctant to borrow in the past and only started taking on large amounts of debt in recent years to expand as it was easy to get credit, she said.

“Everybody encouraged him back then. But now everybody is accusing him of being too aggressive,” Wang groaned. “I don’t understand what is going on — we were pushed to be more ambitious, yet we are now criticized for moving too fast.”

Contact reporter Fran Wang (fangwang@caixin.com)

- 1Cover Story: China Carves Out a Narrow Path for Offshore Asset Tokenization

- 2Drownings Shake Chinese Enthusiasm for Travel to Russia

- 3China Business Uncovered Podcast: A $15 Billion Bitcoin Seizure and the Fall of a Cybercrime Kingpin

- 4Over Half of China’s Provinces Cut Revenue Targets

- 5Li Ka-Shing’s Port Empire Hit by Forced Takeover Amid Panama Legal Dispute

- 1Power To The People: Pintec Serves A Booming Consumer Class

- 2Largest hotel group in Europe accepts UnionPay

- 3UnionPay mobile QuickPass debuts in Hong Kong

- 4UnionPay International launches premium catering privilege U Dining Collection

- 5UnionPay International’s U Plan has covered over 1600 stores overseas