In Depth: How Huawei Prepared for American Sanctions

At the Shenzhen headquarters of Huawei Technologies Co., there are posters everywhere of a World War II Soviet Ilyushin Il-2 ground attack plane shot full of holes and yet still flying. A tagline reads, “Where there is no struggle, there is no strength.”

Ren Zhengfei, founder of Huawei, sees the image as a fitting metaphor for the telecom giant’s position in its titanic clash with the American government. The Il-2 is “managing to make its way back while fixing itself,” the 74-year-old Ren told reporters.

A wartime tension can be felt in the building of the world’s largest telecom equipment maker and second-largest smartphone vendor. Earlier this month, Huawei and its 68 subsidiaries were put on an “Entity List” by the administration of President Donald Trump, effectively banning the company from doing business with American suppliers. The move followed a series of measures taken by Washington targeting the Chinese company last year, including criminal charges and a demand to Canada for the extradition of Huawei Chief Financial Officer Meng Wanzhou, Ren’s daughter.

|

The situation seems to echo that of Huawei’s crosstown rival ZTE Corp., which was hit last year by a similar ban and was forced out of business for months. ZTE, which relies more on foreign technologies, was crippled even though the ban was removed after the company agreed to pay a $1 billion fine, shake up its management and install a compliance team appointed by the U.S.

With more than a third of its products’ components coming from the U.S., the Huawei ban could also be catastrophic. Over the past few weeks, a number of companies including Alphabet Inc.’s Google, chipmaker Qualcomm Inc., Intel, Microsoft and U.K.-based ARM have cut off supplies to Huawei to comply the order, while more global companies and organizations are weighing the impacts of the policy.

However, analysts say Huawei’s situation is different from ZTE’s because of its greater technology capacity and Ren’s long-run strategy of building resilience into the company’s operations. Huawei executives have tried to shrug off the U.S. pressure, citing its stockpiling of key components and work toward becoming more self-sufficient in designing its own replacements for the chips and other parts that now come from American companies.

The company has prepared for years for a possible technology cutoff by the U.S. government, said He Tingbo, chief executive of Huawei’s chip-making arm HiSilicon Technologies Co. Ltd., in an internal memo after the U.S. ban. All of the contingency plans Huawei has developed over the years will be put into use “overnight,” He said.

|

“We have sacrificed individuals and families only for the goal to stand at the top of the world,” Ren told media. With such a goal, he said, conflict with the U.S. was “inevitable.” Thus, Huawei has long worked on backup plans for making its own chips.

But damage from the conflict will not be limited to Huawei, and the fallout will hurt the global technology sector as a whole, analysts said. That is because the Trump sanctions will fracture global tech cooperation and further divide the industry, where interconnection and interdependency is increasingly indispensible.

The ongoing Sino-U.S. trade war adds more complexity to Huawei’s struggle. On May 23, Trump suggested that the fate of Huawei may be linked to the trade talks with Beijing.

Despite calling Huawei “something that's very dangerous,” Trump said, "It's possible that Huawei would be included in some kind of trade deal."

The U.S. attack on Huawei may also alert companies in Europe and Asia that using American technologies could be risky, said Douglas Fuller, an associate professor in the Department of Asian and International Studies at the City University of Hong Kong. The shockwaves of the clash are likely to reverberate through the entire global technology industry, he said.

|

| Ren Zhengfei |

Taking precautions

“We have planned for the worst when we were in the best condition, so when we face the extreme situation, we will keep optimistic,” Ren said in an interview with Caixin.

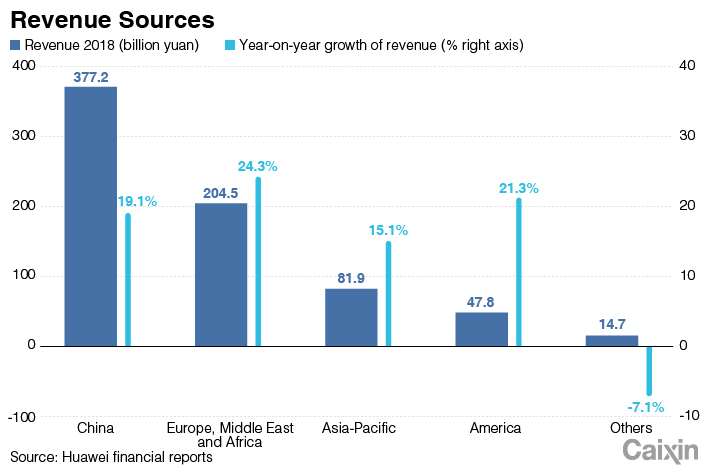

Although business in the U.S. market is marginal for Huawei, a group American companies are its biggest suppliers of key components and services, even larger than its home market on the Chinese mainland, according to an analysis by research house Jefferies. Huawei’s purchases of components from U.S. are worth about $11 billion annually.

Since rival ZTE was hit by the U.S. ban last spring, Huawei has stepped up its search for replacements from domestic suppliers, said Gu Wenjun, chief analyst at ICwise. But most of China’s domestic products lag four to five years behind those made in the U.S. in terms of level of technology, Gu said.

Huawei accelerated procurement to stockpile more components, especially after the detention of Meng in Canada in December on the request of the U.S. While global sales of memory devices slowed since 2018 reflecting oversupply, Huawei was aggressively placing orders for millions of units, a memory device vendor said.

|

An executive of a Huawei device assembler told Caixin that his factory received orders from Huawei in February to stockpile more parts from the U.S. Huawei also required the plant to double production of smartphones and distribute them globally, the executive said.

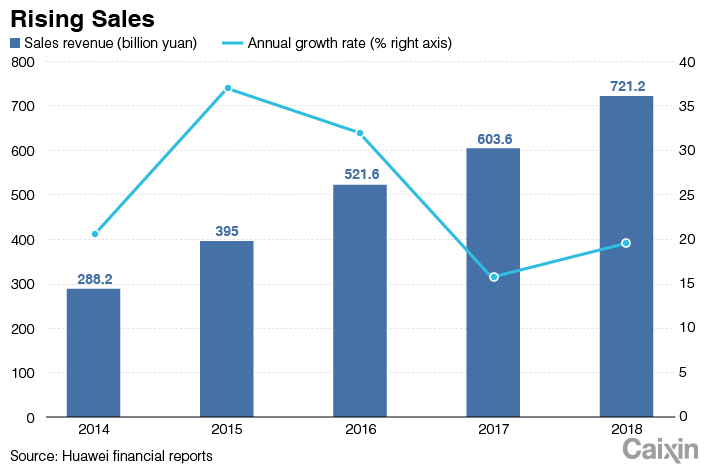

Huawei’s financial report showed that its 2018 spending on raw materials soared 86.5% from 2017 to 35.4 billion yuan ($5.1 billion), while its sales rose 19.5%, indicating the company’s increasing storage of parts.

Some analysts estimated that Huawei has salted away key components to support at least a year of production under the U.S. supply cutoff. Haitong Securities said in a research note that with large stockpiles, Huawei will be able to overcome the U.S. ban in the short term, but if the ban lasts for more than a year, Huawei will need to seek alternative supplies.

Compared with components, it may be more difficult for Huawei to do without some U.S. software suppliers, analysts said. For instance, the market for electronic design automation (EDA) software used for chip design is currently dominated by three American companies — Cadence Design Systems Inc., Synopsys Inc. and Mentor Graphics. Although several Chinese companies have tried to tap into the business, none of them can compete with the U.S. producers.

EDA software is offered through subscription, and if Huawei’s subscriptions expire and not allowed to be extended, its chip design capacity will be directly impacted, said Sui Jing of Strategy Analytics. It is unclear when Huawei’s subscriptions for such services will expire.

Frozen business ties with Google will also hit Huawei hard. The world’s second-largest smartphone-maker has embedded Google’s Android operating system on phones sold in markets outside China. If Google fully implements the U.S. government order, Huawei will have access only to the public version of the Android operating system, meaning Huawei phones could lose access to proprietary apps and services such as the Google Play app store, Gmail and YouTube.

Media reported that Huawei plans to launch its own operating system (OS) compatible with Android for mobile devices as soon as this year, citing Huawei’s mobile business Chief Executive Richard Yu Chengdong.

But analysts said the biggest challenge for Huawei’s self-developed OS is not the technology but cultivating an ecosystem for applications and businesses on the platform, which is not Huawei’s strength.

“The key is time,” said Fang Honggang, former China vice president of Detecon International. “The ecosystem needs to be cultivated slowly, like watering a garden.”

The backup plan

Huawei executives have signaled for years that the company was developing its own chips as a back-up plan. Early in 2012, Ren said that for strategic reasons Huawei was designing its own smartphone operating system and advanced chips. Although some chips that took decades to develop might never be put to use, Huawei would continue the design work, Ren said at that time.

HiSilicon, established in 2004, is the main chip-making arm of Huawei. The company has released more than 200 types of chips geared for smartphones, servers, 5G base stations and artificial intelligence.

HiSilicon has boasted that some of its Kirin series of chips, used for some of Huawei’s smartphones, can compete with the products of Qualcomm and Nvidia Corp. In January, HiSilicon unveiled its first self-developed chipset for base-station servers, the Kunpeng 920.

In an interview with domestic media earlier this month, Ren said Huawei has spent heavily on the backup plans. With the U.S. ban, Huawei will shift more spending to focus on those efforts, Ren said.

But industry experts expressed concerns about whether Huawei’s backup chips designed in-house are sufficiently advanced given the technology gap between China’s tech industry and that of the U.S.

“China’s semiconductor industry still lags far behind the U.S.,” said an industry investor. “For many chips, it is difficult to catch up in three or five years.”

On May 21, HiSilicon posted a long list of recruitment ads, seeking talent for a wide range of chip development-related positions. ICwise’s Gu said it shows that Huawei’s backup plans are already in place and the company is accelerating the rollout of new products with new recruits.

Apart from the HiSilicon expansion, Huawei has quietly launched rounds of internal reorganization since last year, giving greater independence to different business segments and regional branches. Ren said he expected the company to become more vibrant in five years through internal restructuring.

In the face of the headwinds, Huawei may consolidate its business and cut some peripheral departments, Ren said. Staff members in such units will be encouraged to transfer to more-important departments.

In 2018, consumer product manufacturing including smartphones, tablets and other devices accounted more than 48% of Huawei’s overall revenue, followed by 41% from its long-established business with telecom carriers to build networks and base stations. Cloud services for corporate clients contributed the remainder.

No-win situation

Despite U.S authorities’ longstanding mistrust of Huawei and ZTE, a Huawei manager said he thinks the company’s fast-growing competitiveness in the next-generation 5G telecom technology was the main trigger for the recent moves against the company. Huawei’s 5G technology “outpaced rivals by at least 1 to 1.5 years,” the executive said.

According to the European Telecommunications Standards Institute, Huawei held 1,970 5G-related patents as of Dec. 28, 17% of the total and topping all other companies. Nokia Corp. followed with 1,471 patents and Ericsson with 1,444.

Under U.S. pressure, a number of Huawei’s 4G carrier clients have switched to rivals, creating a direct threat to Huawei’s business. But cutting ties Huawei will also be costly for the carriers, especially for those in Europe and Japan, given Huawei’s large presence in local markets, analysts said.

The fallout of the Huawei ban has also shaken the U.S. market. On May 16, the day the ban took effect, stocks of U.S. chip companies declined across the board as orders from Huawei contribute a significant part of the companies’ revenues. Optical components maker NeoPhotonics Corp., which gets half its revenue from Huawei, tumbled more than 20% that day. Large industry players like Broadcom Corp. and Seagate Technology also generate more than 5% of revenue from Huawei.

“The ban will force Huawei and China to speed up domestic research and development to replace U.S. suppliers,” said Sui of Strategy Analytics. “It will hurt the U.S. economy in long term.”

Many analysts say the ban on Huawei is not irreversible as the company will become a bargaining chip in trade talks between China and U.S. Banning Huawei will be a loss-loss situation in which American companies will also be hurt, the City University of Hong Kong’s Fuller said. U.S. companies will urge the administration to ease the restrictions, and the government will be willing to seek a solution that balances national security and economic interests, he said.

Even though Ren has long seen conflict with the U.S. as inevitable, he said he believes Huawei and America will eventually embrace each other as the global economy integrates.

“Maybe after this conflict, there will be no more,” he said.

Contact reporter Han Wei (weihan@caixin.com)

Tomorrow: Huawei founder Ren Zhengfei talks about his take on Huawei headwinds and outlook for business with the U.S. and his biggest concerns in an interview with Caixin

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR