Looking Beyond the Trade War

The market took a deep breath when Chinese President Xi Jinping reaffirmed China’s commitments to open up its economy and lower tariffs in a speech last week at the Boao Forum for Asia. Analysts saw the move as an olive branch to ease trade tensions with the U.S.

In response, U.S. President Donald Trump tweeted that he was “very thankful” for Xi’s remarks and hailed “great progress” to be made. The softening rhetoric soothed fears of escalating confrontation between the world’s two largest economies after Trump proposed to impose new tariffs on $60 billion of Chinese products.

But the shadow of a trade war still looms as the two countries have hurled threats of imposing tariffs on a combined $200 billion of goods in recent weeks. For now, both countries’ tariff proposals are no more than threats. The U.S. Trade Representative’s office by May 22 will collect public comments on levying additional 25% tariffs on 1,300 Chinese product lines, while China pledged to retaliate if the U.S. does take action.

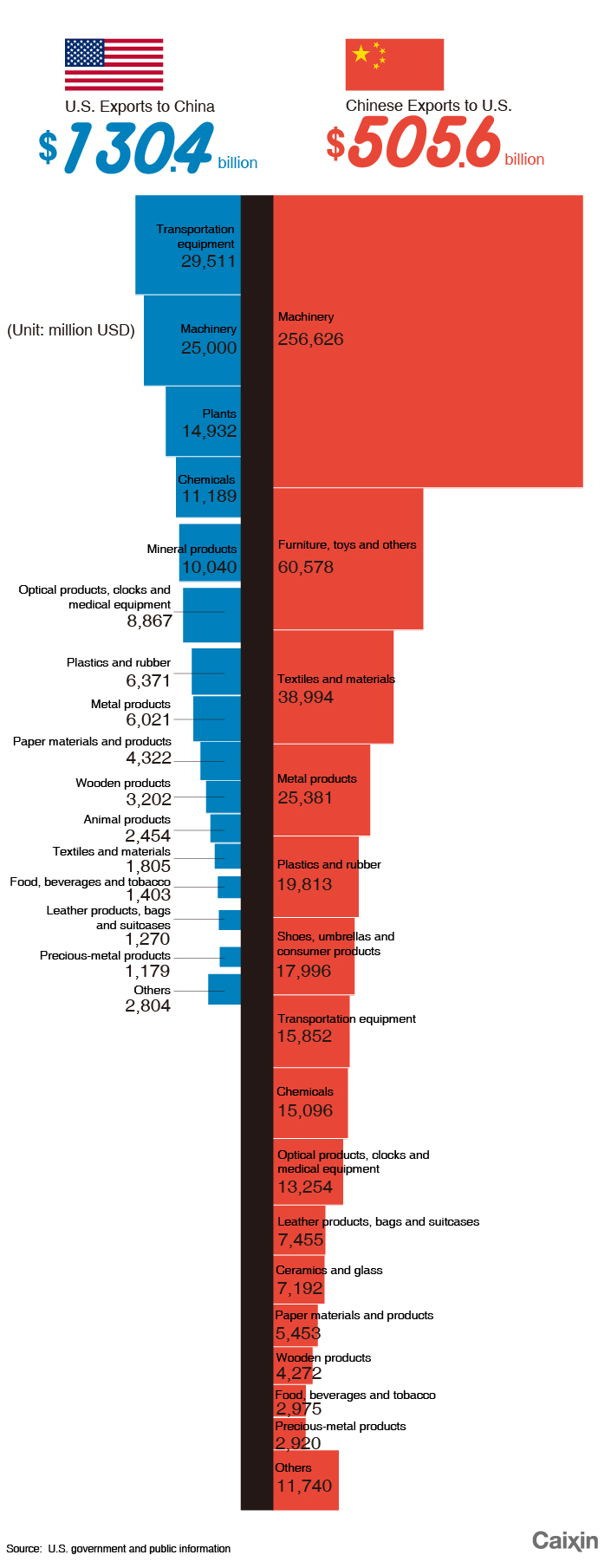

Behind the trade spat is the record high U.S. trade deficit with China. In 2017, the U.S. imported $375.2 billion more from China than it exported to China, up 8.2% from the previous year. Trump has been pressing Beijing to cut the gap by $100 billion. Chinese officials and economists argue that the trade imbalance can’t be solved by China alone and is more reflective of the economic structure of the U.S.

Trade between China and the U.S. exceeded $600 billion in 2017, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. The proposed punitive tariffs from the two sides would affect more than 30% of annual bilateral trade, with tremendous ripple effects on the global market.

The most urgent thing for the two countries is to “rebuild trust through negotiations,” said Jeffrey Schott, a trade economist with the Peterson Institute for International Economics in Washington, D.C.

The trade tensions go deeper than the recent exchange of tariff threats, analysts say.

“If the issue were simply about tariffs, it could be solved overnight,” said Pascal Lamy, former director-general of the World Trade Organization, in an interview with Caixin.

Jennifer Hillman, a Georgetown University law professor and former WTO appellate body member, told Caixin that the Trump administration intends for the threat of punitive tariffs to force China to take measures on issues such as market access, protection of intellectual property rights and reductions in overcapacity.

The two governments’ differing approaches to supporting industrial growth is also at the root of the dispute, according to Tu Xinquan, a trade expert at the University of International Business and Economics in Beijing. While both governments have supported growth in high-tech industries with subsidies, they have taken very different approaches, Tu said. The U.S. mainly supports basic scientific research. China has offered massive subsidies to specific industry applications. The U.S. regards this as creating major market distortions, Tu said.

Differences in the two nations’ approach to the roles of government and markets have made it difficult for China and the U.S. to understand each other, said Alan Larson, a former U.S. deputy secretary of state.

|

“It looks like a trade war, but it actually is a war about future high-tech development,” said one Chinese scholar.

What’s at stake

The list of 1,300 Chinese exports that would be affected by punitive tariffs covers a wide range of industries including machinery, dishwashers, copying machines and printer accessories. Chinese home-appliance makers would be especially hard-hit, analysts said. The U.S. is China’s largest customer for home appliances, buying $15.4 billion of such products in 2017, or more than 22% of China’s total home-appliance exports.

China’s TV makers, including leading players TCL Corp. and Hisense Co., would be hurt the most as exports provide a large portion of their revenue. Manufacturers of refrigerators, air conditioners and washing machines, would be less affected, analysts said.

China’s countermeasures would target 106 U.S. products, including soybeans, cars and aircraft. U.S. soybean farmers, mostly in the Midwest, would be especially affected. China was the largest importer of U.S. soybeans last year, buying $15 billion of them, or a third of total U.S. soybean exports.

U.S. car exporters including Tesla Inc. and aircraft manufacturer Boeing Co. could also be high on the casualty list.

A U.S.-China trade war would also spill over into other economies, sending shockwaves through global markets. For example, exports of U.S.-made vehicles by European auto giants BMW and Mercedes-Benz would be affected. BMW, whose largest factory is in South Carolina, might face $965 million of additional tariffs annually for exports to China, Caixin calculated.

|

Several trade experts interviewed by Caixin said China and the U.S. should seek to solve their trade disputes through the WTO while holding bilateral talks on issues not covered by the organization such as investment.

Beyond the trade war

In his April 10 Boao speech, Xi promised to lower tariffs, impose harsher punishment for violators of intellectual property rights and accelerate the opening of China’s financial markets. Although the speech never mentioned the trade spat, it signaled areas in which China is willing to address U.S. trade concerns, analysts said.

At the same forum, China’s newly appointed central banker Yi Gang detailed measures to further liberalize the country’s financial markets. Yi outlined six coming financial reform policies, including removing limits on foreign ownership of banks and asset management firms, and raising the cap on foreign investment in securities firms, trusts and other financial institutions. Some of these policies are expected to be delivered by June 30, the central banker said.

Sheng Bin, an economics professor at Nankai University, said the leaders’ remarks indicated China’s commitment to opening markets and easing trade tensions with the U.S.

Caixin Insight Group, Caixin Media’s financial data and analysis platform, said in a report that a trade war between China and the U.S. may not actually take place, but tensions may remain for some time, forcing China to move faster with reforms.

Although Xi’s speech at Boao marked no major shift in policies he and other Chinese officials have promoted in recent years, it is likely to push forward the implementation of reform plans at a faster pace, said Cui Fan, a trade professor at the University of International Business and Economics in Beijing.

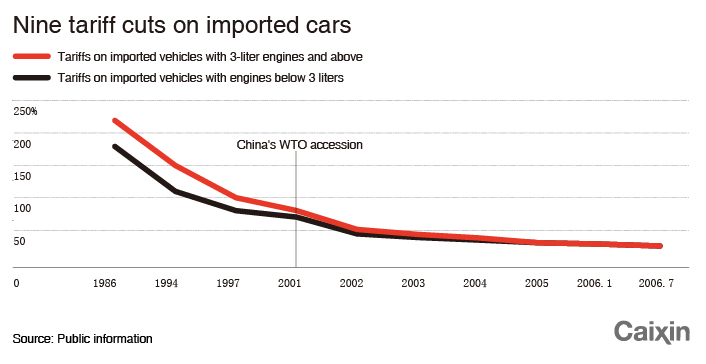

Xi set a timetable for releasing detailed plans to loosen restrictions on foreign investment by June 30 and for reducing the 25% tariff on car imports by the end of this year. China will also ease restrictions on foreign investors’ shareholding in auto manufacturing joint ventures.

A source close to policymakers said detailed arrangements need to be worked out on the order and pace for implementing the pledges. If the tariff cut and easing of shareholding control were put in place at the same time, the auto market would face a reshuffling that could hurt domestic automakers, the source said.

Zhang Monan, a researcher at the China Center for International Economic Exchanges, said the next step in China’s market-opening reforms will focus on service sectors, including manufacturing services. Emerging industries such as biopharmaceutical and environmental protection will also be further opened up to the outside world.

But Xi did not mention service sectors such as telecommunications, education and health care – all closely watched by foreign investors. Analysts said the omissions may reflect either that policymakers haven’t reached consensus on further reforms in those sectors, or that issues in those industries might be saved for negotiations between China and the U.S.

This story has been updated to correct a figure about the additional amount of tariffs that BMW might face on exports to China.

Contact reporter Han Wei (weihan@caixin.com)

To read more about China-U.S. trade tensions, click here

- 1Cover Story: China Carves Out a Narrow Path for Offshore Asset Tokenization

- 2Drownings Shake Chinese Enthusiasm for Travel to Russia

- 3China Business Uncovered Podcast: A $15 Billion Bitcoin Seizure and the Fall of a Cybercrime Kingpin

- 4Over Half of China’s Provinces Cut Revenue Targets

- 5Li Ka-Shing’s Port Empire Hit by Forced Takeover Amid Panama Legal Dispute

- 1Power To The People: Pintec Serves A Booming Consumer Class

- 2Largest hotel group in Europe accepts UnionPay

- 3UnionPay mobile QuickPass debuts in Hong Kong

- 4UnionPay International launches premium catering privilege U Dining Collection

- 5UnionPay International’s U Plan has covered over 1600 stores overseas