Four Things to Know About China’s Latest Crackdown on Cryptocurrencies

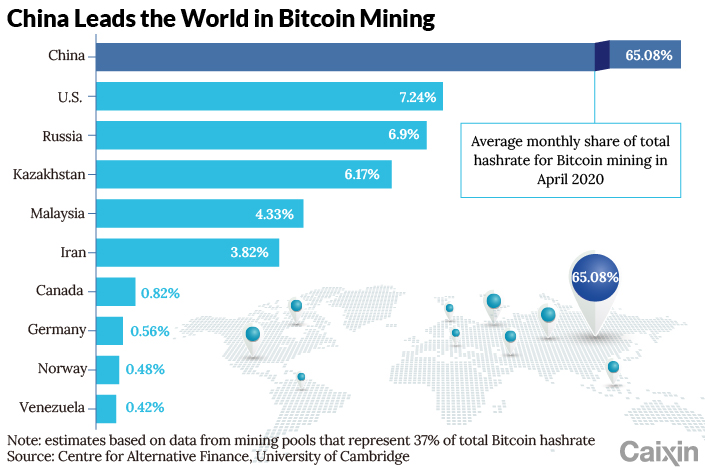

As Bitcoin mania grips the world, China has opened a new front in its war on cryptocurrencies.

From the miners that produce the virtual assets and the local governments that host them, to the exchanges that provide the trading platforms and the financial institutions that facilitate the traders who use them, everyone is under attack.

The aim — to crush speculation that could threaten financial stability, prevent fraud and money laundering, and choke off a booming crypto mining industry that’s jeopardizing efforts to cut power consumption and curb pollution.

The past seven weeks have seen an intensification of a long-standing campaign against cryptocurrencies that began in 2013, when China dominated an industry that was still in its infancy. That year, regulators prohibited (link in Chinese) financial and payments institutions from conducting Bitcoin-related business, though they allowed individuals to trade Bitcoin “at their own discretion and risk.” Four years later, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) and other regulators upped the ante with a ban on initial coin offerings (ICOs), which they declared a form of illegal fundraising, and shut down domestic cryptocurrency platforms that facilitated such deals. Now, another four years on and with the battle far from won, regulators are on the attack again.

The central bank and Beijing’s municipal financial regulator said Tuesday that they will shut down a company based in the city that was suspected of providing software services for cryptocurrency trading, the latest enforcement of the ban on providing cryptocurrency-related services for customers.

Although China has now banned cryptocurrency trading outright, it is not the only major economy to be concerned about the risks. In June, the U.K.’s financial watchdog banned Binance Markets Ltd., a unit of one of the world’s biggest cryptocurrency exchanges, from doing business in the country, and the U.S. is mulling regulations amid growing evidence that cryptocurrencies are being used for money laundering and terrorism financing. On June 28, Mexico’s financial regulators said (link in Spanish) that financial institutions would not be allowed to trade or offer services based on cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin, and that carrying out and offering operations with crypto assets without authorization would be seen as a violation of regulations and open a company to sanctions.

But financial risks are only part of the story. China’s pledges to support a green economy and its commitments to achieve carbon neutrality have shone a light on the environmental cost of producing cryptocurrencies. As a result, the crackdown on the downstream activities of how they are traded has now been broadened to include the upstream business of how they are created.

Read more

Analysis: Does China Plan an Even Tougher Crypto Crackdown

1. What’s new in the latest crackdown?

Two things — a bigger focus on dismantling cryptocurrency mining, and a broadening of curbs on financial institutions to stop them from handling transactions and providing services to customers that facilitate the buying and selling of virtual assets.

The cascade of bad news started on May 18 when three self-regulatory bodies issued a joint notice banning financial institutions and payment companies from directly or indirectly providing cryptocurrency services to customers, including accepting the currency as payment.

That was followed on May 21 by a meeting of the State Council’s Financial Stability and Development Committee (FSDC), a top-level economic and financial policymaking body chaired by Vice Premier Liu He. The committee is tasked with ensuring financial stability, controlling risks and improving supervision and regulation of the financial sector.

A three-paragraph readout (link in Chinese) from the meeting, which covered a series of issues, devoted just one line to cryptocurrencies: “crack down on Bitcoin mining and trading behavior, and resolutely prevent the transmission of individual risks to society.”

This was the highest-ranking body in China to refer to a crackdown, and it was the first time the FSDC had directly referred to cryptocurrencies. It sent shockwaves through the cryptocurrency world.

In June, the PBOC met with representatives from Industrial and Commercial Bank of China Ltd., Agricultural Bank of China Ltd., China Construction Bank Corp., Postal Savings Bank of China Co. Ltd., Industrial Bank Co. Ltd., and Alipay, the payment service of fintech giant Ant Group Co. Ltd. Central bank officials reinforced May’s ban on financial institutions and payment companies providing cryptocurrency services to customers, according to a statement (link in Chinese) issued by the central bank.

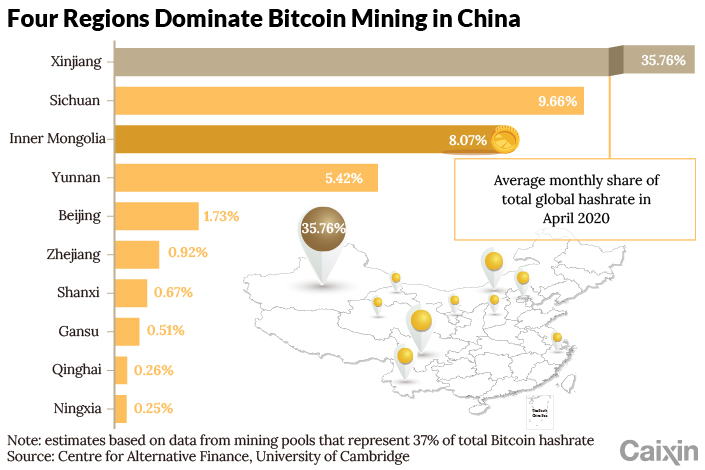

The crackdown on cryptocurrency mining had been building for some time. The National Development and Reform Commission proposed classifying it as a sector to be eliminated (link in Chinese) in the draft of its updated Industrial Structural Adjustment Guidance Catalog published in April 2019, although the designation was removed in the final version. But pressure on the industry picked up again this year. In late February, Inner Mongolia said it proposed to ban new cryptocurrency mining projects and shut down the entire industry by the end of April as part of a plan to meet central government targets for reducing energy consumption over the coming five years.

Since the FSDC’s statement, authorities in China’s other major cryptocurrency mining hubs have sprung into action, with the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, and Qinghai, Yunnan and Sichuan provinces all announcing rectification campaigns that include a ban on new mining projects, along with orders for existing mines to close and for power plants to cut off supplies to suspected mining pools (矿池).

|

2. What’s behind the crackdown?

Worries about the environment, financial stability, and speculation.

The government is concerned that the business of churning out and verifying digital coins is consuming vast amounts of power and damaging the environment just as the world’s largest carbon emitter is working to meet pledges to reach peak greenhouse gas emissions before 2030 and achieve carbon neutrality by 2060.

Cryptocurrency coins are produced through a mining process that involves using powerful, sophisticated specially made computers to solve complex computational math problems. But the power required to run the machines has led miners to move to areas where electricity costs are low, and some regions have even issued policies to encourage them.

|

Sichuan, whose mountainous regions have plenty of hydropower plants, announced a plan (link in Chinese) in 2019 to support businesses to move to areas with high excess capacity during the rainy season, and in 2020 released a list (link in Chinese) of “model” companies that consumed excess hydropower (水电消纳示范企业) that included several cryptocurrency mining companies.

But the impact on the environment is worrying policymakers. China’s energy consumption from mining Bitcoin, by far the dominant cryptocurrency, will exceed the total energy consumption of countries like Italy by 2024 and its carbon emissions will top the annual greenhouse gas emissions of Spain and the Netherlands, a study published in April by researchers in China, the U.S. and U.K. estimated.

Read more

Sichuan to Shutter Crypto Mining in Sweeping Crackdown

Given the government’s commitment to cutting carbon emissions and greening the economy, it was inevitable that cryptocurrency mining’s days were numbered.

The issue of financial stability is not new. Policymakers have long been concerned that the anonymous and decentralized nature of cryptocurrencies makes it difficult to track transactions and monitor financial crime. Regulators have said that cryptocurrency trading is speculative and risky, and facilitates money laundering, fraud, illegal cross-border fund transfers and tax evasion. It could also undermine China’s proposed digital currency, which is aimed at maintaining the PBOC’s ability to control the financial system.

Even though cryptocurrency exchanges have been banished from the Chinese mainland, many investors have managed to skirt the regulations. That’s partly because Chinese financial institutions continue to facilitate trading on exchanges and over-the-counter (OTC) platforms and fail to carry out detailed checks to ensure that money going in and out of customers’ accounts isn’t related to cryptocurrency transactions. The PBOC’s meeting with banks and the country’s dominant third-party payments platform, Alipay, was aimed at sending a clear message that financial institutions need to step up their compliance.

Betting on cryptocurrencies has been profitable for many traders — Bitcoin’s price surged nearly 500% to over $63,300 from October 2020 to mid-April — and the potential rewards have led some companies to divert funds away from their normal operations to invest in cryptocurrency ventures. The trend has become a growing concern for the government, which is on a mission to ensure that companies are serving the real economy, not speculating.

Hangzhou Lianluo Interactive Information Technology Co. Ltd. (002280.SZ) is a prime example. The company, which sells consumer electronic products and offers internet financial services, poured $14.3 million into a project investing in mining machines, virtual currency trading and ICO companies in 2019, according to a company filing (link in Chinese) to the Shenzhen bourse on May 24. But it wrote off the value of the investment in its 2020 accounts and reported a loss of $5.1 million on the project that year.

3. What’s the impact and who’s affected?

The casualties include companies that make and sell mining rigs (矿机), conduct proprietary mining, offer hosting (托管) services to customers or operate mining pools where individual miners (矿工) combine their processing capacity (算力) to mine the virtual assets and split the rewards.

Financial institutions that process and facilitate cryptocurrency transactions and services are also likely to suffer as they are forced to step up efforts to ensure compliance with government regulations, adding to their cost base and hurting their fee income. Exchanges where the assets are traded will also be hit.

The impact on individuals and professionals in China who deal in cryptocurrencies is almost impossible to quantify because of the lack of data about their participation on the exchanges.

The world’s three largest producers of Bitcoin mining machines are Chinese — BitMain Technologies Holding Co. (比特大陆), and Nasdaq-listed Ebang International Holdings Inc. (亿邦国际) and Canaan Inc. (嘉楠科技) Together they accounted for 95% of the market in terms of computing power sold in the first half of 2019, according to estimates from U.S. consulting firm Frost & Sullivan. BitMain, the dominant player with a 65% market share, is unlisted.

But company statements and stock exchange filings show that these producers, whose main market is China, have for some time either been planning, or are already implementing plans, to shift operations overseas in anticipation of a more hostile environment.

Ebang, which makes more than 90% of its revenue from China, said in a May 28 statement that it expects “no direct or immediate impact.” Its proprietary mining operations are already overseas, customers who buy its machines will simply move them overseas, and Chinese citizens and those using Chinese IP addresses are already banned from trading on its cryptocurrency exchange platform, the statement said. The company has already halted its mining machine hosting business in China and switched its focus to building compliant mining farms in North America and Europe using renewable energy wherever possible.

Both Ebang and Canaan acknowledged in their earnings reports that the price of Bitcoin has a significant impact on their operations and finances. Consequently, the slump in price since the latest regulatory crackdown emerged is likely to hurt near-term earnings, although Zhang Nangeng, the CEO of Canaan, said during an earnings call on June 1 that the company would be cushioned to some extent because of the volume of upfront payments it receives from customers. Nevertheless, he acknowledged that some domestic miners offloading second-hand rigs may be “underselling,” which contributed to the drop in the price of machines for immediate delivery by 20% to 30% from the level achieved when Bitcoin’s price was around $60,000.

BitMain has temporarily suspended spot sales of its mining machines globally, as some Chinese customers are reselling their machines to “recoup funds or avoid keeping mining machines in China for too long,” which has led to a glut of second-hand equipment, the company said in a statement (link in Chinese) on June 24.

Several equipment manufacturers have or are in the process of setting up proprietary and hosted mining operations in regions including North America, Europe and Central Asia, where Kazakhstan has emerged as a hot destination. Shenzhen-based mining firm BIT Mining Ltd., which is listed in the U.S., announced on May 24 that it planned to invest $9.3 million in a cryptocurrency mining data center in Kazakhstan with a local partner. On June 21 it reported that it had delivered 320 mining machines to Kazakhstan and expected to deliver another 2,600 before July 1, with its remaining equipment set to be moved to overseas data centers over the coming quarters.

But this strategy is not without risk.

“In places like Kazakhstan and Russia, where gangs run rampant and there’s collusion between business and government, there’s a risk that mining machines will be confiscated under the guise of some kind of inspection,” the head of a large domestic mining pool told Caixin.

Cryptocurrency exchanges are also being hit. Many survived the regulatory onslaught in 2017 by shifting their operations overseas, where they continue to serve domestic investors via peer-to-peer networks and OTC trading platforms (场外交易平台) that can only be accessed via virtual private networks that are mostly illegal in China.

Read more

Initial Coin Offerings Slide Past Ban for China Comeback

OKEx, Binance, and Huobi are among the world’s top cryptocurrency exchanges. They were all started by Chinese entrepreneurs and are all based outside the Chinese mainland. Although they are banned in China, they still serve mainland Chinese customers whose transactions are routed through their banks or fintech platforms such as Alipay that offer nonbank payment services.

But the exchanges will find it much more difficult to continue to service their customers as a result of May’s crackdown. As well as reinforcing the ban on providing services linked to cryptocurrency trading, the central bank has ordered financial institutions to carry out sweeping checks of accounts to identify any links to virtual currency exchanges and OTC platforms, and break any payment links they discover immediately.

4. Can regulators triumph?

China’s regulators frequently find themselves in a cat and mouse game with the companies and sectors they are meant to be supervising, and it remains to be seen how successful the current campaign will be on both the environmental and trading sides.

Some mining sites have bought their own hydropower equipment to generate electricity and have mounted their machines on trucks that can be moved quickly at a moment’s notice to avoid on-site inspections, a person who has surveyed mining sites told Caixin. Some operators have also bribed local officials to turn a blind eye to their operations to allow them to skirt regulations, an industry insider said.

While it may be hard to conceal large mining pools, small-scale operations are much more of a problem to track down. A few rigs set up in an individual’s home or a few dozen machines installed in a warehouse or next to a small hydroelectric plant in a remote area would be unlikely to attract attention, the head of the domestic mining pool told Caixin.

“The regulatory authorities definitely want to shut down (mining), but this is very difficult to achieve,” a senior researcher in the industry who declined to be identified told Caixin. It could even spur the development of new ways of mining, for example through mobile phones or other devices, the researcher said.

Trading may be an even harder target to regulate because transactions on OTC platforms are so difficult to trace. Although data is scarce, there’s plenty of anecdotal evidence that Chinese investors are still a significant presence in the cryptocurrency trading world in spite of the longstanding ban.

The other perennial problem that financial regulators in China face is enforcing their own rules, and the cryptocurrency issue is no exception. Their ability to compel financial institutions and nonbank payment platforms to comply with the order to hunt down cryptocurrency traders and shut down their links to exchanges will be key to the success of the latest crackdown.

Contact reporter Luo Meihan (meihanluo@caixin.com) and editor Nerys Avery (nerysavery@caixin.com)

Download our app to receive breaking news alerts and read the news on the go.

Get our weekly free Must-Read newsletter.

- PODCAST

- MOST POPULAR